Benedict Force - Murmansk, Russia

Kills to 151 Wing in Russia.

81 Squadron.

12th Sept Z5122 P/O 'Bas' Bush. Bf110 Damaged.

12th Sept Z4018 Sgt Haw Bf109E Destroyed.

Z5157 P/O Walker Bf109E Destroyed.

Z4006 Sgt Waud. Bf109E Destroyed.*

Z4006 Sgt Waud. He126 Probable*

Sgt Smith was damaged/could not open cockpit and crashlanded and was killed.

17th Sept Z5208 Sgt Haw. Bf109E Destroyed.

Z4017 P/O Bush Bf109E Destroyed*

Z5207 Sgt Anson 1/3

Z5228 Sgt Sims. 1/3 Bf109E Destroyed.*

BD792 S/Ldr Rook. 1/3

26th Sept Z5227 P/O Edmiston. Bf109F Probable

BD818 P/O Holmes Bf109F? Destroyed

Z4006 Sgt Reed Bf109F? Destroyed.

F is more likely an E with a pointed spinner?

27th Sept Z5227 P/O Edmiston. Bf109F? Destroyed.

Z4018 Sgt Haw. Bf109F? Destroyed.

6th October. Z5207 F/Lt Rook. Bf109F Destroyed.

BD792 S/Ldr A H Rook/Furneaque Ju88 Destroyed*

BD792 S/Ldr Rook/P/O Ramsay Ju88 Probable

Z5157 P/O D Ramsay/134 a/c Ju88 Probable

Z5228 F/O McGregor Ju88 Probable

Z5209 P/O Walker Ju88 Probable

BD822 Sgt Bishop Ju88 Damaged.

Z4006 Sgt Crewe Ju88 Damaged

134 Squadron.

6th October Z3978 P/O Cameron Ju88 Probable

Z3978 P/O Cameron Ju88 Damaged

Z5134 Sgt Gould Ju88 Damaged

Z5236 F/O Elkington/Barnes Ju88 Destroyed *

* Confirmed in Luftwaffe loses.

_____ Confirmed as hitting the ground by independent RAF pilots, not Russians Observation Corp

Absturz- Hurricanes151 Wing v Bf109E’s I/JG77.

12th September 1941

One Bf110 damaged.(Diary report)

1.(Z)/JG77 Bf110 Jagerbeschuss Oblt F/ Lt M

Three Bf109E’s and one Hs126 were claimed as shot down.

German Luftwaffe records indicate the following:

(1) 1./JG77 Bf109E-7 W.Nr1075 ‘Gelb 6’ by Liza-Bucht, Luftkampf, 100% Ltn Eckerdt v. d. Lühe gefallen.

(2) 1./JG77 Bf109E-7 W.Nr4078 by Nicht Gemeldet,. Notlandung infolge Motorstorung. 100%.

(3)1./(H)32 Hs126 W.Nr3461 by location Lizabucht. Reason Jagerbeschuss Air Combat 30%.

17th September 1941

Three Bf109E’s were claimed as shot down.

German Luftwaffe records indicate the following:

(1) 14./JG77 Bf109E-3 W.Nr4004 ‘Rot 6’ by Zapad Liza. Jagerbeschuss 100%. Fw Joseph Stiglmair Vermißt.

(2) 14./JG77 Bf109E-7 W.Nr6124 by Bereslawi, Jagerbeschuss-20% (recorded as 4./JG77).

26th September 1941

Two Bf109E-7’s were claimed as shot down and one probable.

No German Luftwaffe records indicate any damage to Bf109’s on this day.

27th September 1941

Two Bf109F’s (E-7’s?) were claimed as shot down.

No German Luftwaffe records indicate any damage to Bf109’s on this day.

6th October 1941

One Bf109E’s was claimed as shot down. (A flight of six of I/JG77 were escorting the Ju88’s)

(German Luftwaffe records for the 6th October indicate the following -

(1) 3./KG30 Ju88 A-5, W.Nr 626, 4D+LL. Location Unbekannt-unknown, Unbekannt-unknown, 100%. Crew missing. (West of Veanga)

(2) 3./KG30 Ju88 A-5, W.Nr 4155 4D+KL. Location Unbekannt-unknown, Unbekannt-unknown, 100%. Crew missing. (West of Vaenga)

(3) 2./KG30 Ju88 A-5, W.Nr 292 4D+?K. Location Fl. Pl Petsamo-. Brauchlandung nach Jagerbeschuss, 100%.

Two Ju88's crashed behind front line in the tundra and a number of members of crew were capture. Aircraft were basically undamaged. Where are those aircraft now!

If anyone can add anything more to this, then that would be very interesting. Shame there is no JG77/KG30 day log records adding more information.

Combat Losses source: 12oclockhigh.net - http://forum.12oclockhigh.net/showthread.php?t=10928&page=3

The Eastern Front

Hitler invaded Russia on 22 June 1941 as part of Operation Barbarossa. In an attempt to divert Luftwaffe resources away from the Eastern Front, Fighter Command increased the number of fighter sweep and escort missions across the Channel. Despite these efforts, the situation on the Eastern Front continued to deteriorate, leaving Stalin with little option hut to appeal to Britain for support.

Two Squadrons to Russia

Towards the end of July 1941, Winston Churchill agreed to send two squadrons of Hurricanes to the Murmansk area in northern Russia for two reasons: first, to help protect the area of Murmansk so that much-needed supplies could still reach the Red Army through the vital ice-free port; and, second, to train Russian pilots and ground crews in the flying and maintenance of the Hurricane. Some of Fighter Command’s most experienced pilots were taken from their units to form these two squadrons. Many of them had gained valuable experience during the Battle of Britain, and they were sorely missed by Fighter Command for several months.

The response to Churchill’s pledge was immediate. The two units formed for this special task were 81 and 134 Squadrons, both re-formed at Leconfield at the end of July. The man chosen to lead the wing throughout the campaign in northern Russia was Wg Cdr Henry Ramsbottom-Isher-wood. Born in New Zealand in 1905, Henry Neville Gynes Ramsbottom-Isherwood had served as an officer in the New Zealand territorial army before being commissioned into the RAF in 1930. He had served in India and the Middle East before becoming a test pilot during the build-up to war, and had been awarded the AFC in 1940.

81 Squadron

Following the outbreak of war, 81 Squadron had re-formed in France as a communications unit. However, after the fall of France during the summer of 1940, it had returned to the UK and had disbanded. The squadron re-formed at Leconfield on 29 July 1941, and was initially made up of pilots from ‘A’ Flight of 504 Squadron. This unit had distinguished itself during the previous summer and many of its pilots were already combat veterans. Chosen to lead this new unit was Sqn Ldr Tony Rook. Born in Nottingham in 1918, Anthony Hartwell Rook was commissioned into the Auxiliary Air Force in 1937, and was one of two Rook cousins who had both served with 504 Squadron with distinction during the battles of France and Britain. Both had already, coincidentally, achieved kills during the same combat on the same day, 27 September 1940, when the squadron had scored notable success. Tony Rook led 81 Squadron in Russia, while his cousin Micky Rook was posted as a flight commander to 134 Squadron; both Rooks would, therefore, continue to serve together on the Eastern Front.

Another ‘504 veteran’ joining 81 Squadron was Pit Off ‘Artie’ Holmes, who had achieved fame on 15 September 1940 when he shot down the Dornier Do 17 which was believed to have bombed Buckingham Palace. Two other ‘504 vets’ were Fg Off Alan McGregor and Fit Sgt ‘Wag’ Haw, a promising youngster who, at twenty-one, was beginning to prove himself as an excellent fighter pilot.

134 Squadron

In similar circumstances, 134 Squadron re-formed at Leconfield on 31 July, essentially consisting of pilots from 17 Squadron. This squadron had also served with distinction during the Battle of Britain; its new commanding officer was Sqn Ldr Tony Miller. Born in Calcutta in 1912, Anthony Garforth Miller had been commissioned into the Auxiliary Air Force before the war, and had assumed command of 17 Squadron at Tangmere during August 1940. He was a natural choice to be the first commanding officer of the new squadron. His two flight commanders could not have been more contrasting in appearance: at six feet four inches, Micky Rook was at one time apparently the tallest pilot in the RAF (and probably the tallest person to fly the Hurricane); the other, Jack Ross, was less than five feet tall, and probably the smallest pilot to have flown the Hurricane!

The only other Battle of Britain veteran from 17 Squadron to join 134 Squadron was Neil Cameron. He had served as a sergeant pilot with 1 and 17 Squadrons during the battle, and was commissioned on joining 134 Squadron. After the war he went on to a most distinguished career in the RAF, becoming Marshal of the RAF Sir Neil Cameron, KT GCB CBE DSO DFC in July 1977.

The two squadrons were the spearhead ol 151 Wing, which officially formed at Lecontield on 12 August 1941. While it' pilots were spending a few days on leave, thirty-nine Hurricane MkllBs were sent from 1 lawaden to Liverpool, where twenty-four were prepared tor flying and put on to 1 IMS Argus; these would he the first Hurricanes to land on Russian soil. The remaining fifteen were packed in crates and placed as cargo on other ships. On returning from leave on 16 August, the pilots flew in 1 landley Page I larrows from Lecontield to Ahbotsinch on the outskirts of Glasgow. The final destination tor hoth squadrons was still secret and most had no idea where they were going, except that it was overseas. They were transported hy truck to Gourock, where the main party hoarded various ships.

The convoy that sailed tor Russia on 21 August consisted ot some thirty ships, including the flat-decked HMS Argus, which accommodated most ot the squadron's pilots, the cruiser Sheffield, and the destroyers Active anil Electra, with most ot the wing’s ground crew and support personnel embarked in S.S. Llanste/yhen Castle. The RAF detachment hound for Russia totalled 550 men, and it was well out to sea before they were told of their final destination.

Argus was an old Italian merchant ship that had heen captured during the First World War and later converted as a flat-decked carrier. The superstructure had heen removed, which meant that a flight deck of some 350 feet (100m) was available. For the pilots on board, the voyage-proved rather dull, with very basic liv ing conditions. The twenty-four Hurricanes carried below deck were only partly assembled. Although the majority ot the pilots had flown Mkls, they had no experience on the Mkll. The improved Merlin XX series engine would give them better performance and the twelve 0.303in machine-guns would improve the firepower. Nevertheless, the fact remained that they would have to take otf on a short flight deck, which was something that none ot them had ever done before!

Arrival

After three weeks aboard Argus, the moment had come. The twenty-four I Hurricanes had heen assembled and were now ready for departure. Each was carrying a reduction in armament of only six guns, in order to reduce the all-up weight. The procedure used tor take-off was for Argus to steam into wind at her maximum speed of seventeen knots. It was the morning of 7 September and a typical early autumn day in northern Russia: overcast, grey and cold. The pilots gathered on the flight deck to await their turn tor departure. First otf was 1 34 Squadron, led by Tony Miller, followed by 81 Squadron. Sgt ‘Wag’ I law was seventeenth off and his log hook shows the flight to Vayenga airfield lasting one hour and ten minutes.

On arrival in Russia, the wing was placed under the command ot the I lead ot the Soviet Navy and Naval Air Service, Admiral Kuznetsov. That same day, a conference was held at Archangel between the RAF stalf in Russia and Adm Kuznetsov, and it was decided not to make 151 Wing operational until all the guns and ammunition had arrived at Vayenga. At that time, each Hurricane was fitted with just six guns and HO rounds of ammunition, and a signal had to be sent to hasten delivery of vital armament and spares. Although these supplies were delivered within forty-eight hours, it was found that the guns had gun blast tubes and sears from Hurricane Mkls, which would not tit, and did not have tire and safe mechanisms attached. Following much improvisation in local workshops, two aircraft from each flight of each squadron were stripped ot their guns, enabling each flight to have four aircraft of eight guns.

The Campaign Begins

Vayenga - The Base

The airfield at Vayenga (otherwise spelt ‘Vaenga’ or ‘Vianga’) was located just over 20 miles (35km) to the north-east of Murmansk, facing the Arctic Ocean, 170 miles (275km) north of the Arctic Circle. It was to he home to the two squadrons throughout the campaign. It was a large base with no real runway, just a I a rue area of hardened sand surrounded by hills and woods. It had none of the facilities normal to an RAF base - no radar to provide early warning, and only limited communications. This meant that the pilots could only meet the threat once they were already airborne, using their eyes and the smoke puffs of the local gunners to locate the enemy aircraft. One other point of concern to the I Hurricane pilots was the question of aircraft recognition amongst the Russian ack-ack gunners.

Despite these complications, the pilots had to concentrate on the task ahead. 1 hey were there tor two reasons: first, to help defend the port of Murmansk, and second, to help convert Russian pilots to their new I Hurricanes once they had been unpacked and assembled. The first snow was due and the pilots were unsure just how long they would be expected to carry out their task before the long, severe Russian winter set in.

The arrival of the RAF created tremendous local interest at Vayenga, and they had to host important visits from senior Russian officers and officials. No flying was carried out on the first three days, for a number of reasons: the British ships had sailed on to Archangel to off-load the main party of the convoy more safely, out of reach of enemy air activity, and there was much site maintenance to be done before the wing would be ready tor operations; second, the weather was already deteriorating; and, third, the Russian food had already posed a problem, and it would be several days before some individuals would adjust to the change in diet!

Fifteen Hurricanes were taken to Archangel, where an ‘erection party’ responsible for assembling the aircraft made them ready for use at Keg-Ostrov airfield. This engineering detachment of two officers, one warrant officer, three flight sergeants, two sergeants and thirty airmen was led by the wing engineering officer, Fit Lt Gittins. Conditions at Keg-Ostrov were poor, and many of the specialist tools required for assembling the Hurricanes were missing.

Basically, the procedure was as follows: unpack each Hurricane from its packing case (about one hour); jack it up and attach the basic fuselage components; lower it on to the undercarriage and push it into the hangar; fit the wings and tail units. The aircraft were then fuelled and armed before ground-testing. The process was slow and, despite the party working in three groups, the facilities were not available. Aircraft components had been packed in a hurry in the UK, and there were obvious difficulties in unloading and unpacking the components in terrible weather conditions. However, improvisation and hard work by the erection party meant that the first three Hurricanes were completed and air-tested on the sixth day, and all fifteen Hurricanes were assembled and tested within the first nine days. It was a magnificent achievement! The squadrons were ready for action only six weeks after Churchill had promised Stalin his support.

Operations Commence

The first sorties took place from Vayenga on 11 September, when the squadrons

each flew eight aircraft on local familiarization sorties; the front line was not far away, about 15 miles (25km) in places, and it was essential that the pilots knew their way around before engaging the enemy for the first time. It was deemed necessary to make certain adjustments to the Merlin engines to compensate for the low-octane fuel and the cold operating temperatures. The 95-octane fuel in particular led to the Merlin engine cutting out on pilots during the first day; this happened to Jack Ross in Z3763, and Neil Cameron in Z3978. That same night the first snow tell.

During the following morning, various supplies began to arrive at Vayenga. Six more Hurricanes were flown in from Archangel, having stopped to refuel at Afrikanda. Three more Hurricanes were stranded at Afrikanda, after failing to start following refuelling. This meant that a starter battery and accumulators had to be sent to Afrikanda from Vayenga, so that the aircraft could be recovered the following day.

First Success

The first combat patrol was flown that same day, 12 September, by three 1 lurn-canes of 1 34 Squadron. Although enemy bombers were sighted, no combat took place. This was followed by a patrol by 81 Squadron and two escort missions by 134 Squadron for Russian bombers. Although these first missions did not lead to any activity, Hurricanes were soon in combat for the first time. Later that same day, at 3.05 p.m., the four Hurricanes of 81 Squadron were scrambled to meet enemy aircraft sighted to the west of Murmansk. Leading the patrol was ‘Wag’ Haw (Red Leader), with Pit Oft Jimmy Walker (Red 2), Sgt ‘Ihby’ Waud (Blue Leader), and Sgt ‘Nudger’ Smith (Blue 2) completing the section. They soon sighted five Messer-schmitt Bf 109s escorting a Henschel 126 in the distance. Pressing home a determined offensive, Haw delivered a close-quarter attack against one Bf 109, which burst into flames before rolling inverted and crashing to the ground. In less than thirty minutes, the Henschel 126 and two of the other Bf 109s were also shot down, one by Walker and the other by Waud, who also claimed the HS 126. Success was theirs, although, sadly, ‘Nudger’ Smith was killed during the encounter.

Wag Haw’s report for that first encounter shows that the combat took place at 3.25 p.m. to the west of Murmansk. He continued:

Whilst leading a patrol of Hurricanes over the enemy lines I intercepted five Bf 109s escorting a HS126. My height was 3,500ft. The enemy aircraft were approaching from ahead and slightly to the left, and as 1 turned towards them, they turned slowly to the right. I attacked the leader and as he turned I gave him a ten second burst from the full beam position. The enemy aircraft rolled on to its hack and as it went down it hurst into flames. I did not see it crash owing to raking evasive action, hut Red 2 confirms that it crossed him in a 70-degree dive at 500ft, smoke and flames still pouring from it.

News of this first success travelled fast to the highest of authorities. The RAF’s Chief of the Air Staff, ACM Sir Charles Portal, sent the following signal to Adm Kuznetsov, to commemorate the first operations carried out by 151 Wing in Russia:

British squadrons arc now operating from Soviet territory against the common enemy. On this first and memorable occasion of our two Air Forces fighting side-by-side on Russian soil I send you the warmest congratulations of all ranks of the RAF on the skilful and heroic resistance maintained by the Soviet Air Forces collaboration between our two Air Forces.

Adm Kuznetsov’s reply included the following:

I am sincerely happy at the tact that the lucky chance of beginning operations against the common enemy side-by-side with the RAF on an important part of the Front has fallen to the Air Force of the Soviet Navy. 1 take this opportunity of expressing to you, Air Chief Marshal of the British Royal Air Force, my sincere regards and respect.

The Hurricanes had been in Russia for just four days and enjoyed their first success, hut the loss of‘Nudger’ Smith was sadly felt by all, serving to remind the pilots of the seriousness of the task ahead. He was buried two days later on a piece of high ground overlooking Murmansk Sound.

During the next two days, the weather was very bad, although both squadrons were involved in local patrols. The last six Hurricanes to be erected at Keg Ostrov flew into Vayenga on 16 September, with the remainder of the erection party arriving during the following day. By this time, 81 Squadron was flying sixteen fully armed Hurricanes, each with all twelve guns. However, there were still the occasional problems caused by grease blocking the gun mechanisms due to the extremely cold conditions.

Further Success

On 17 September, there was further success, when 81 Squadron was scrambled to intercept a number of enemy aircraft to the west. The weather conditions were ideal, and the enemy was soon sighted. The engagement took place at 6.55 p.m. over the enemy lines to the west of Murmansk and, during the forty-five minutes the sortie lasted, the squadron shot down four aircraft, including another Bf 109 for ‘Wag’ Haw. His combat report reads:

1 was leader of Yellow Section. Two Bf 109s dived over and passed in front of us. I attacked the second enemy aircraft as he turned and dived westwards. I made an astern attack at about 200 yards range, firing a three-second burst with no visible effect. The enemy aircraft then turned to the right across me and I delivered a quarter attack from about 150 yards, firing another burst of three seconds. During this attack smoke began to pour from the enemy aircraft, a large piece flew oft him and he rolled onto his back and went into a vertical dive. An enemy pilot who baled out was identified by the Russian Observer Corps as being the pilot of the machine which 1 attacked. The piece of the enemy aircraft which flew off was probably the hood being jettisoned.

Apart from being scrambled to intercept enemy aircraft, Hurricanes from both squadrons were involved in carrying out escort duties for Russian bombers attacking targets across the front line. Some of these were relatively short-range missions, while others were longer. One of the longer missions took place on 24 September, when Hurricanes provided an escort for Russian Pe-2 dive-bombers. The route went over the area of Petsamo (to the west of Murmansk), across Finland and into Norway, before returning to Vayenga, and took one and a half hours.

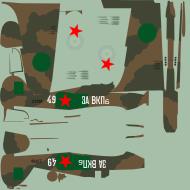

Training

By the end of September, the pilots of 1 51 Wing had begun their secondary task -; training Russian pilots to ily the Hurricane. The Russians believed very strongly in leading from the front. The first Russian pilot to fly the Hurricane was Admiral Kuznetsov on 25 September. As the Head of the Soviet Naval Air Service, he was given his own Hurricane (Z5252), with his own number and a red star painted on it. The next day, the second Russian pilot to fly the Hurricane was Lt Col Boris Safonov, a 26-year-old ace fighter pilot of the 72nd Regiment of the Soviet Naval Air Service, and the third was Kapitan Kuharienko. Both of these famous pilots would later feature in the success of the Hurricane in Russia.

It worked out that most of the training flying was carried out by 134 Squadron, in particular by Jack Ross, who formed an excellent partnership with his Soviet counterpart, Kapitan Kuharienko. Another of the Russian instructors involved in this early training programme was Kapitan Yacobenko, who later went on to command the first Soviet Hurricane squadron. The RAF pilots found their Russian colleagues keen to learn about the Hurricane. They all adapted quickly and showed remarkable determination and plenty of guts. It was not uncommon for a Russian pilot to carry out his first flight in the Hurricane in marginal weather conditions, but they seemed to have no fear.

As well as the flying training, the RAF ground crews had started training their Russian counterparts in servicing and maintenance techniques. Snow had con-tinued to fall, much more heavily now, and the RAF and the Russians were in a race against time before the worst of the weather set in. Vayenga was covered in snow and ice, and routine maintenance was proving increasingly difficult.

The End of the Campaign

27 September

On 27 September, Wag Haw destroyed another Bf 109, bringing his personal score to three in two weeks. The combat took place at midday about 45 miles (75km) to the north-west of Murmansk. Haw’s report reads:

I was White leader in a formation of four Hurricanes when I sighted four Bf 109s approaching us from the west. The leader of their second section tried to do a beam arrack on me but 1 turned towards him and after three complete turns 1 was on his tail. I gave him several short bursts and while doing this we lost height down to 3,000ft. As 1 fired the last hurst but one, the enemy aircraft came out of its turn, climbed steeply, and then stalled and went into a spin, white and black smoke pouring from it. I did not see what happened to it, as there was an enemy aircraft on my tail. 1 got rid of this and returned to base.

This third kill for Wag Haw was confirmed.

During the two weeks of combat, the Hurricane wing had destroyed ten enemy aircraft for the loss of just one. It had managed to operate from Vayenga with relatively little interruption, apart from the occasional attack by German bombers, none of which scored any notable success. There was, however, a tragic accident on 27 September, when two ground crew were holding down a Hurricane (BD825) during engine run-up. The aircraft got airborne, but it stalled just after take-off, and the pilot, unaware of the crew’s position, crash-landed, with severe injury to himself and tragically killing both men on the ground.

The weather took a turn for the worse during the final few days of September, and conditions at Vayenga deteriorated badly.

Final Claims

Due to a certain amount of being in the right place at the right time, all the early combat success had belonged to 81 Squadron - the squadron’s pilots had destroyed twelve enemy aircraft - but it was soon the turn of 134 Squadron to get some reward for their efforts. On 6 October, Tony Miller led 134 Squadron to success, when it shot down two Junkers Ju 88s, and claimed a further three probables.

These aircraft destroyed, and a further kill by 81 Squadron, proved to be the final claims, bringing the wing’s total to fifteen enemy aircraft destroyed for the loss of one Hurricane. These remarkable figures may even have been an under-estimate. Many more aircraft were claimed as probables, hut the nature ot the surrounding countryside, with so many deep lakes, meant that wreckage could not be found, and these probables could not be confirmed.

The Weather Worsens

By the end of the first week of October, the RAF’s task was nearing its end - there was no further operational flying, and the training of the Russian pilots with the newly assembled Hurricanes was almost finished. The training did not go without incident, however — two Hurricanes crashed on landing during the first week of October, without injury to the pilots. Similar accidents had happened at the Hurricane training units in the UK and, considering the weather and operating conditions, the Russians were considered to be remarkably quick learners.

On 9 October, a blizzard hit Vayenga and, during the next two days, there were further heavy snow showers. At this time, only the Russians were flying Hurricanes, as this extreme change in weather brought to an end the RAF’s campaign in northern Russia. By 12 October, most of the wing’s Hurricanes, and the newly assembled aircraft, had been handed over to the Rus-sians, and the RAF detachment prepared to leave Russia. The next week was spent in more training with the Russian pilots and ground crew, with some operational sorties being flown by the wing. By the end of the week, more than twenty Russian pilots were operational on the Hurricane.

Departure of the RAF

The First Russian Hurricane Squadron

The first Russian unit to equip with the Hurricane was 1 Russian Hurricane Squadron, which formed at Vayenga on 18 October under the command of Kapitan Yakobenko. The following day, the first Russian Hurricane Wing of three squadrons was formed at Vayenga under the command of Lt Col Safonov, with Kapitan Kuharienko as his second in command. Safonov went on to become one of Russia’s most famous fighter pilots; he loved the Hurricane and had become a very good friend of the RAF fighter pilots at Vayenga. In his 224 operational sorties, he shot down thirty enemy aircraft, before being killed in action on 30 May 1942, while protecting one of the many Allied convoys into Murmansk. He was twice made a Hero of the Soviet Union, as well as being decorated with the Russian Order of Lenin and the Order of the Red Banner.

A Job Well Done

With the formation of the first Russian wing, the task of 151 Wing was complete. There was no possibility of keeping the RAF in Russia, because of the immense logistical problems involved in supporting a detachment so far from the UK. There was now the question of what to do with 151 Wing; if it could not stay in Russia, where should it go? It was first suggested that it should be sent to the Middle East where it would he most welcome; after much discussion, however, it was decided not to go ahead with this plan, because of the major problem of transporting the wing such a great distance. In the end, it was decided that 151 Wing would return to the UK and then disband.

It was four weeks before the RAF detachment was ready to leave Russia, and the main challenge became how to keep 550 airmen occupied, now that their task was complete. Temperatures w'ere as low as -30 degrees centigrade, and, in fact, this marked the beginning of one of the coldest winters in the Murmansk area; later, Fit Sgt (later Sqn Ldr) ’Wag' Haw, DFC DFM Order of Lenin - 81 Squadron

Bom on 8 May 1920, Charlton Haw was educated at Tang Hall School in York, before working as an apprentice lithographer. He joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve in 1938 and carried out his elementary flying training at Brough. Aged just nineteen, he was called for active service on 1 September 1939 and, following initial training at Bexhill, was posted to No 5 Flying Training School at Sealand. On completion of training on the Miles Master, he was posted directly to 504 Squadron, on 19 June 1940. He flew Hurricane Mkls with the squadron throughout the Battle of Britain, during which he achieved his first 'kill', shooting down a Messerschmitt Bf 110 over Bristol on 27 September.

Haw remained with 504 Squadron until the formation of 151 Wing, and he was posted to the newly re-formed 81 Squadron at Leconfield on 28 July 1941. He flew Hurricane MkllBs with the squadron from Vayenga, near Murmansk, and was the top-scoring RAF fighter pilot in Russia during this short campaign. Having left the Hurricanes behind in Russia, the squadron returned to the UK and converted to the Spitfire MkV. In March 1942, Haw was commissioned, and continued to serve with 81 Squadron until the end of July. He then served as a flight commander with 122 Squadron at Hornchurch, again flying the Spitfire. In February 1943, he was given command of 611 Squadron at Biggin Hill and then 129 Squadron at Hornchurch from November 1943 until July 1944, during which time the squadron converted to the Mustang Mklll. Haw was awarded the DFC on 17 October 1944, after which he was rested from operations.

After the war 'Wag' Haw commanded 65 Squadron from 1946 to 1948, then lost his flying category on medical grounds, which resulted in him leaving the RAF in 1951 to become the landlord of a pub in Sussex. He then acquired a boarding kennel, and developed a pet-food business, which he ran for the rest of his working life. Still very much remembered by the Russians, he visited Moscow in 1985 as a guest to join celebrations for the 40th anniversary of the end of the war. He lived near Farnham in Surrey until his death in December 1993. In May 1995, 'Wag' Haw's unique group of medals went to auction at Christie's, where it was snapped up by the author of this book!

temperatures would drop as low as -47 degrees centigrade. A limited amount of physical exercise was possible, but most of the pilots and ground crew preferred to go to the Russian squadrons to assist in further training when necessary.

The wing embarked in various Royal Navy ships from 20 November, and began the long journey home. The largest group joined the cruiser HMS Kenya at Murmansk, setting sail on 28 November, and arriving at Rosyth in Scotland on 7 December. With the disbandment of 151 Wing, its members were sent off for some well'earned leave. They were surprised to be hailed as national heroes on their return, unaware that news of their exploits had preceded them.

The expedition of 151 Wing had undoubtedly been a success. The Russians were now fully operational with the Hurricane, and the wing had helped ensure that the Germans had made no further gains on the Eastern Front, leaving the vital port of Murmansk free. The RAF’s Hurricane pilots had led from the front, achieving confirmed kills of a ratio of fifteen to one, plus many more probables, possibles and damaged, the final sum of which will never be known. As well as these obvious achievements, the wing had made many friends and helped boost relations between Britain and Russia during a critical time of the war. Russia had been desperate for help when Stalin made his first appeal to Churchill but, coincidentally, the day that the wing returned home was the day that the United States entered the war. The beginning of the severe Arctic winter meant that Russia was safe for the time being and by the following year things would be much more promising. As soon as 151 Wing had left Murmansk, the Russians immediately began the request for more Hurricanes. By the end of the war, a total of 2,952 Hurricanes had been sent to Russia as part of 14,000 aircraft sent to the Eastern Front by Britain and the United States; this represents more than 20 per cent of the total number of Hurricanes built.

Hurricanes sent to Russia from 1941

- MARK NUMBER

- MkllA 210

- MkllB 1,557

- MkllC 1,009

- MkllD 146

- MkIV 30

The Russians made certain modifications to the standard marks of Hurricane; they fitted 0.5 in machine-guns, and developed tandem variants, including one with a dorsal gun position. There was also at least one Sea Hurricane Mkla (V6881), which was ‘adopted’ by the Russians. It had originally been launched by catapult from the SS Empire Horn during a convoy patrol and, following action with an enemy aircraft, was unable to return to the ship, landing instead at Keg Ostrov airfield.

The Russians were enormously appreciative of the efforts of 151 Wing, and awarded the Order of Lenin to four of the pilots who took part in the expedition. This show of gratitude was unique, the only time that the Order of Lenin was awarded to any Allied forces during the Second World War. The four awards were made to Wg Cdr Ramsbottom-Isherwood (for leading the overall RAF detachment), to Sqn Ldrs Tony Rook (OC 81 Squadron) and Tony Miller (OC 134 Squadron), and to the top-scoring pilot, Flight Sgt ‘Wag’ Haw of 81 Squadron. This award of a Soviet Order to Haw, a non-commissioned officer, was unique; the citation given with it is most interesting, handwritten by the Commander of the Soviet Northern Fleet, and dated 29 November:

To Pilot of the Royal ‘Military’ Air Fleet of Great Britain, SERGEANT HAW C.F.

1 congratulate you with the high Government award of the Union of Socialist Republics, the ‘Order of Lenin’. Your manliness, heroism and excellent mastery in battles of the air have always assured victory over the enemy. I wish you new victories in battles against the common enemy of all progressive nations, i.e. - German fascism.

RAF 151 Wing (commanded by Wing-Commander H.N.G.Ramsbotton-Isherwood), consisting of two Hurricane-equipped squadrons, 81 and 134 Sqns (led by Sqn Ldr Tony Rook and Sqn Ldr Tony Miller respectively), was dispatched to Russia by sea in mid-August 1941 as Force Benedict, with a total of 40 Hurricane Mk.IIB fighters. 24 Hurricanes were loaded aboard the escort carrier HMS Argus, from which they took off to Vayenga 7 September. Meanwhile convoy PQ 0 (Operation Dervish) had arrived in Arkhangelsk 31 August with 16 Hurricanes in crates, which were assembled at the AF base in Keg-Ostrov from where the aircraft departed to Vayenga between 12 and 16 September. As the Northern Fleet AF had only 48 obsolete Soviet fighters (I-153, I-16 and I-15bis) at its disposal at that moment, the arrival of the Hurricanes provided an eagerly needed and significant reinforcement of the defence of Murmansk and the naval bases in the region.

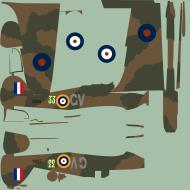

151 Wing used a unique identification systems in Russia, adopted to satisfy both own and Russian needs: the second letter of the RAF squadron letters (FL for 81 Sqn and GY for 134 Sqn) was replaced by an individual letter (e.g. "L" - "N") and a sequential number was added ("55"). These tactical numbers of 134 Sqn A Flight were in the 20's, 134 Sqn B Flight in the 30's, 81 Sqn A Flight in the 40's and 81 Sqn B Flight in the 50's correspondingly. The Flight Commanders got the full numbers: eg. S/Ldr Rook's was 50 and S/Ldr Miller's was 20.

RAF 151 Wing in Vayenga, September 1941 (aircraft/pilot allocation as on first flight)

81 Squadron (from HMS Argus)

134 Squadron (from HMS Argus)

Flight

Serial

Tactical code

Pilot

Flight

Serial

Tactical code

Pilot

A

BD792

F_-50 (later FR-44)

S/Ldr Rook

A

Z5205

G_-20

S/Ldr Miller

A

Z5228

F/O McGregor

A

Z5206

F/Lt Berg

A

Z4017

FU-56

Sgt Waud

A

BD823

Sgt Campbell

A

Z5209

P/O Walker

A

Z4013

P/O Sheldon

A

Z4018

FH-41

F/Sgt Haw

A

Z5134

Sgt Gould

A

Z5157

P/O Ramsay

A

Z5159

GV-33 (ex GO-25)

P/O Elkington

B

Z5122

P/O Bush

A

BD699

Sgt Clarke

B

Z5207

Sgt Anson

A

Z5253

GA-25

P/O Furneaux

B

Z3746

FA-40

Sgt Smith, KIA 12.9.1941

B

Z3763

GY-30 (later -60?)

F/Lt Ross

B

Z4006

FV-54

P/O Edminston

B

Z5120

Sgt Barnes

B

Z5227

FE-53

Sgt Reed

B

Z3978

P/O Cameron

B

Z3977

FN-55

Sgt Rigby

B

Z5210

Sgt McCann

81 Squadron (from Keg-Ostrov)

134 Squadron (from Keg-Ostrov)

A

Z3768

FK-49

Sgt Crewe

A

Z5236

GO-31

Sgt Kirvan

A

BD822

Sgt Bishop

A

Z5123

Sgt Keil

A

BD824

FA-47

Sgt Mulroy

B

BD825

GH-27, crashed 27.9.1941

P/O Wollaston

A

Z5208

FA-48

Sgt Carter

B

Z5226

Sgt Fry

B

BD818

P/O Holmes

B

Z4012

GU-35

Sgt Knapton

B

BD697

F/Lt Rook

B

Z5303

GC-26 (or GG-26?)

Sgt Douglas

B

Z5252

Sgt Sims

B

BD790

GP-36

Sgt Griffiths

B

Z5211

Sgt Griffiths (the fate of one Hurricane of PQ-0 is unclear)

151 Wing performed its first operational sortie from Vayenga 12 September claiming three Bf 109Es and one Hs 126 damaged over Petsamo for the loss of Sgt N.Smith in Z3746.

151 Wing claimed 11 Bf 109 and 3 Ju 88 shot down during its short stay in northern Russia, with only one total loss. However, according to German records Luftwaffe lost only three Bf 109 and three Ju 88 to 151 Wing Hurricanes.

The last sortie of 81 Sqn was flown 8 October, and handover of the Hurricanes to the Air Force of the Northern Fleet (VVS SF) started five days later. By 22 October the remaining 36 Hurricanes had been transferred to the Soviets. One of the spare Hurricanes, Z5252 was already 25 September symbolically handed over to Maj.Gen. A.A.Kuznetsov, C.O. VVS SF.

Luftwaffe losses to RAF 151 Wing in Northern Russia

Date

Type

W.Nr.

Tactical no

Unit

Crew

Comments

12.9.1941

Hs 126

3461

1.(H)/32

Litsa, 30 % damage by fighter

12.9.1941

Bf 109 E-7

1075

yellow 6

1./JG 77

Lt. E. von der Lühe KIA

10 km E Litsa

12.9.1941

Bf 109 E-7

4078

I/JG 77

10 km E Litsa

17.9.1941

Bf 109 E-3

4004

red 6

1./JG 77

Fw J.Stiglmair MIA

Litsa

17.9.1941

Bf 109 E-3

6124

14./JG 77

Oblt. E.Wintergest

Bereslavl, 20 % damage by fighter

6.10.1941

Ju 88 A-5

088.0292

4D+_L

I/KG 30

BF Uffz W.Sellge injured

Air combat, W/O after landing in Petsamo

6.10.1941

Ju 88 A-5

088.0626

4D+LL

3./KG 30

Lt. H.Servos, Uffz H.Kamme, Fw A.Mau and Ogfr E.Funke KIA

Air combat, Ura Guba

6.10.1941

Ju 88 A-5

088.4155

4D+KL

3./KG 30

Uffz R.Habermann, Gefr H.Kratz, Gefr K.Wetzleberger, Ogfr B.Zimmerhackl KIA

Air combat, Ura Guba

(2 Germans POW?)

Meanwhile evaluation of Hurricane Mk.II Z2899 (the very first Hurricane handed over to the Soviets) had already commenced on 22 September 1941 at NII VVS (Soviet Air Force Research Institute) with Col. K.A.Gruzdev as responsible test pilot.

14 October 1941 78 IAP (commanded by B.F.Safonov) was formed to receive the 36 serviceable 151 Wing Hurricanes. In March 1942 the Hurricanes with pilots were transferred from 78 IAP to Safonov's old regiment (which meanwhile, 18 January 1942 had been elevated to Guards status as 2 GSAP). 2 GSAP, now commanded by Safonov received gradually more Hurricanes and P-40s (both Tomahawk and Kittyhawk) from arriving convoys.

RAF 151st Wing had performed a total of 365 missions during its stay at Vayenga. Wing-Commander Ramsbotton-Isherwood, Squadron Leaders Rook and Miller, and Flt Sgt Haw were awarded the Order of Lenin 28 November 1941. The engineering officer Flt Lt Gittins was later awarded the Order of the Red Star. Four Soviet pilots (B.F.Safonov, Capt. A.A.Kovalenko, Escadrille C.O. 2 GIAP, A.N.Kukharenko, Deputy C.O. 78 IAP, and I.Tumanov, C.O. 2 GSAP) were reciprocally awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross 19 March 1942.

5 July 1942 RAF formed a six-squadron 153 Wing (under the same command as 151 Wing) for intended dispatch to Russia. However two weeks later this order was cancelled, apparently because of the big losses of convoy PQ17.

During the Battle of Moscow winter 1942 Hurricanes equipped also e.g. 1 GIAP and 157 IAP on the Kalinin Front. In spring-early summer 1942 considerable numbers of Hurricanes were delivered to the Karelian Front, where Hurricanes amounted to over half of the fighters on 1 July 1942 (133 Hurricanes of a total of 244 fighters).

Simultaneously (early spring 1942) a program for rearmament of Hurricanes with Soviet cannons and guns had been initiated, as calibre and fire power of the original British armament (up to twelve 7.62 mm Browning machine-guns) was considered too weak.

Two alternative replacements of four Browning machine-guns were proposed by the gun designer B.G.Shpital'nyj together with specialists of Zavod No.115 (co-located with Yakovlev's OKB) in Moscow:

1) four 20 mm ShVAK cannons, two 7.62 mm ShKAS machine-guns and six racks for RS-82 rockets, or

2) two 20 mm ShVAK cannons, two 12.7 mm UBK machine guns and six racks for RS-82 rockets.

After evaluation by NII VVS from 28 December 1941 to 3 January 1942 the first alternative was adopted.

Even before official conclusion 30 SAM of VVS SF replaced four Browning machine-guns with two 12.7 mm UBT and two 50 kg bombs as proposed by Boris Safonov in VVS SF. Armoured pilot seat backs were also installed.

The armament modifications were mainly made at Zavod No.81 in Monino, Zavod No. 89 in Gorkiy and in workshops of 6 IAK in Podlipki, but also in several frontal units (eg. VVS SF). A total of some 1.200 Hurricanes were re-equipped with Soviet armament.

Because of lack of spares for the Merlin Mk.XX engines installation of Soviet M-82A, M-88 or M-105 engines was studied, but this proposal was not adopted.

In spring 1942 VVS SF was in urgent need of light bombers, and 120 Hurricanes were modified to carry two under-wing mounted 100 kg bombs.

Because of the relatively big number of Hurricanes in VVS SF special two-seater training Hurricanes were considered necessary, and 10 aircraft were modified with a second cockpit and double command. In order to save weight eight of the twelve machine guns, the armoured seat back of the pilot etc. were dismounted. A number of two-seaters were also used without double command for courier purposes, and one two-seater was further modified as "ambulance" aircraft and used by 10 AE VVS SF.

Several two-seater Hurricanes were also used at the Glider Aviation School of Red Army Paratroop Forces (VAPSh VDV KA) in Saratov for towing Antonov A-7 and G-11 transport gliders, and a number of operational sorties were also performed.

Other Soviet Hurricane modifications included a tactical recce version with an AFA-I camera in rear fuselage (used eg. by 118 RAP SF and 3 GIAP KBF), experimental fixed and retractable ski-undercarriages etc.

In summer 1942 it became evident that Hurricanes were no match for Bf 109 "Filips", and the Hurricanes were gradually transferred to PVO-regiments in the Soviet rear. At least 26 GIAP (of 7 IAK, later 2 GIAK) of the PVO Army in Leningrad used Hurricanes as night fighters until spring 1944.

In autumn 1943 and early 1944 some 45 Hurricane Mk.IID and 30 Mk.IV intended for ground-fighting (equipped with 40 mm cannons) were delivered. Evaluation and conversion training showed clearly that cannon-equipped Hurricanes were inferior to Il-2s already in major production, and were thus not used for frontal sorties. On 1 July 1943 there were already 495 Hurricanes in PVO-regiments and 1 June 1944 the PVO-Hurricanes numbered 711.

One spectacular incident took place deep in the Soviet rear, when four Hurricanes of 1./933 IAP (of 144 IAD; piloted by st.lt. P.G.Dergachev, ml.lt. G.N.Sevastyanov, ml.lt. P.N.Grachev and ml.lt. N.A.Lopusov) strafed a Ju 290 A-9 (W.Nr. 110185, A3+CB) of 1./KG 200, which had landed in the Kalmykian steppes at night 22-23 May 1944. This aircraft had taken off from Zilistea in Romania, carrying some thirty Kalmykian “freedom fighters”, with the task to assist the resistance movement in Kalmykia, recently recaptured after the German occupation (Unternehmen Salzsee).

Lend-lease fighter conversion training was mainly performed in various ZAPs (Reserve Aviation Regiments), of which the first was 27 ZAP in Kadnikov (Keg Ostrov) in the Arkhangelsk-Vologda region. 16 May 1942 6 ZAB (Reserve Aviation Brigade), comprising of 14 and 22 ZAP, was formed in Ivanovo, which become the main conversion training centre.

In the Ural Military District Hurricane conversion training was provided by 17 ZAP.

The first Soviet Hurricane downed by Finnish AF was BD761 piloted by st.lt. N.F.Repnikov, 152 IAP who crashed mid-air with Sgt. T.Tomminen, LeLv 28 in Morane-Saulnier MS.406 MS-329 at Karhumäki (Medvezhegorsk), Eastern Karelia on 4 December 1941, killing both pilots. For his “taran-victory” Repnikov was posthumously awarded the HSU 22.2.1943.

Several Hurricanes of the Karelian Front Air Forces were shot down by Finnish Air Force in 1942-1943. Four force-landed Hurricanes (Z2585, Z3577, BM959 and BE559) were considered repairable, but ultimately only Z2585 (of 152 IAP, force-landed at Tuoppajärvi in early February 1942) was restored to flying condition in Finland. This aircraft became HC-452 in Finnish Air Force, and performed its first flight in Finnish colors on 13 October 1943.

Hurricane deliveries to USSR:

According to Russian archives the total number of Hurricanes received in USSR was 3082, including following subtypes: Mk.IIA (210), Mk.IIB (15), Mk.IIC (786), Mk.IID (45), Mk.IV (30), Mk.X (40+340+149), Mk.XI (150), Mk.XII (248), Mk.XIIA (and 39 Mk.Is modified to Mk.IIA status).

Hurricane deliveries to USSR, serial ranges:

P5195 (Mk.X), Z2310...5480 (Mk.IIA, IIB and IIC), V6881 (Sea Hurricane), AE958...977 (Mk.X), AF945...AG344 (Mk.X), AG665...684 (Mk.IIB, Mk.X), AM271...369 (Mk.X), AP517...879 (Mk.IIB), BD697...959 (Mk.IIB and IIC), BE162...711 (MkIIB and IIC), BG674...BH360 (Mk.IIB), BM932...959 (Mk.IIB and IIC), BN105_481 (Mk.IIB and IIC), BP268...657 (Mk.IIB and IIC), BV165 (Mk.I to IIA conversion), BW835...984 (Sea Hurricane, Mk.X, Mk.XI), BX102...124 (Mk.IIB to IIC conversions, Mk.X), DR339...391 (MkI to IIA conversions), HL549...994 (Mk.IIB and IIC), HV279...880 (Mk.IIB and IIC), HW117...879 (Mk.IIB, IIC and IID), JS219...468 (Mk.IIB to IIC conversions, Mk.XII), KW113...777 (Mk.IIC and IID), KX125...888 (Mk.IIC, IID and IV), KZ234...858 (Mk.IIC and IID), LB991 (Mk.IIC), LD205 (Mk.IIC), LE529 (Mk.IIC), LF223...596 (Mk.IIC and IV), PJ660...872 (Mk.IIB to IIC conversions, Mk.XII), PS 444...790 (Mk IID).

Identified Soviet Hurricane operators (a total of 29 fighter regiments were equipped with Hurricanes in 1941-42):

Soviet Hurricane Units:

- VVS SF: 2 GIAP (ex 72 SAP, Vayenga, Dec 1941–summer 1942), 78 IAP (Nov 1941-), 27 IAP (Vayenga, winter 1943-), 118 ORAP, 10 AE, 30 AE, 3 UAP, 9 UTAP (spring 1942-), 3 AG: 11 UAE (summer 1942-), OMAG: 13 AP (autumn 1942)

- VVS BVF: 53 AP, 54 AP

- VVS KBF: 3 GIAP (ex 5 IAP, Kronstadt, Lavansaari, June-Oct 1942)

- PVO:

- - 1 VIA (Moscow, spring 1943-);

- - 6 IAK (Moscow, Nov 1941-): 67 IAP (Feb 1942-), 429 IAP (Feb 1942-), 488 IAP (1942-);

- - 7 IAK (Leningrad): 26 GIAP (night fighter regiment; ex 26 IAP, Pushkino, Gorskaya; autumn 1942-spring 1944), 191 IAP (1942);

- - 8 IAK (Baku, summer 1942-);

- - 9 IAK (Voronezh, spring 1943-; Kiev late autumn 1943-);

- - 10 IAK (Rostov, spring 1943-; Dnepropetrovsk, late autumn 1943-; Lvov, late 1944-);

- - 36 IAD (Gomel, spring 1944-; Lyublino, late 1944-);

- - 2 GIAD (ex-102 IAD, Stalingrad, autumn 1942-; Ploesti, late 1944-): 515 IAP (autumn 1942-), 628 IAP (summer 1942-);

- - 104 IAD (Arkhangelsk region, spring 1942-): 348 IAP (Yagodnik, April 1942-), 729 IAP (Obozerskaya, Barakitsa, Vas’kovo), 730 IAP (Kegostrov);

- - 106 IAD (Bologoye, autumn 1942-, Velikiye Luki late autumn 1943-): 246 IAP (Mk. IID, Jan-Aug 1944), 441 IAP (Bobrujsk);

- - 122 IAD (Murmansk): 767 IAP (Ushmana, spring 1942-), 768 IAP and 769 IAP (Boyarskaya, spring 1942-);

- - 124 IAD (Vypolzovo, spring 1944-);

- - 126 IAD (Vienna, spring 1945-);

- - 141 IAD (Zhitomir, spring 1944-);

- - 148 IAD (Tsherepovets, Aug 1942-; Korosten, spring 1944): 933 IAP (Kalmykia, 1943-), 964 IAP (Tikhvin, 1943-1944);

- - 298 IAD (Tbilisi, autumn 1942-);

- - 310 IAD (Valujki; spring 1943-);

- Karelian Front (VVS 14.A, VVS 19.A, VVS 26.A, VVS 32.A, 7 VA): 19 GIAP (Shongui, spring-summer 1942), 20 GIAP (Murmashi, spring-summer 1942), 152 IAP (Segezha, Dec 1941-1943), 195 IAP (Montshozero summer 1943 ?), 197 IAP (Murmashi, spring 1942–1944), 435 IAP (Beloye more -Kirovsk, spring 1942–summer 1944), 609 IAP (Afrikanda, Sekehe, Dec 1941–spring 1943), 760 IAP (Boyarskya, Dec 1941–summer 1943), 835 IAP (Kirovsk, spring-autumn 1942), 837 IAP (Montshegorsk, spring 1942-), 839 IAP (Kond Guba winter 1944?), 841 IAP (Segezha, autumn 1942-), 858 IShAP (Peski, summer 1944-), 17 GShAP (ex 65 ShAP, Poduzhemye spring 1942–Nov 1942), 80 BAP (Kolezhma, 1942-1943?), 9 UTAP (Onega 1942)

- Leningrad Front: 12 OKAE (1942), 50 OKAE

- Kalinin Front: 1 GIAP (ex 29 IAP, Jan 1942-); 256 IAD: 157 IAP (Jan 1942-)

Other sectors:

- - 6 VA, 239 IAD: 485 IAP (1942)

- - 16 VA, 215 IAD: 246 IAP (Mk.IID, Jan-Aug 1944)

- - 246 IAP was based in Adji-Kabul for conversion training with Hurricanes (II D and IV) from January 1944. This regiment was attached to 16 VA in July 1944, still using Hurricane II Ds until September 1944. No frontal missions were however performed with the ageing Hurricanes.

- - 235 IAD (summer 1942): 46 IAP, 180 IAP, 436 IAP

- - 235 IAD was attached to 8 VA. In addition to the mentioned three regiments (46, 180, and 436 IAP) also 191 IAP was briefly equipped with Hurricanes. The division was practically annihilated in late summer 1942 (“Operation Blau”).

- - 201 IAD: 179 IAP (late 1941-summer 1943)

- - 438 IAP, 814 IAP (1942), 13 OKAE (1942), VAPSh VDV KA (Glider Aviation School of Red Army Paratroop Forces, Saratov), Kachinskaya Krasnoznamennaya Aviatsionnaya shkola im. tov. Myasnikova (1942-)

151 Wing to Murmansk

by Wing Commander (Tim)

John Francis Durham Elkington CB, DFC & Bar

After Hitler’s failure to dominate the skies over Britain in 1940, he turned his attention to Russia with Operation Barbarossa on 22 June 1941. Stalin was taken by surprise and, with his air force immediately crippled, he sought an alliance with Churchill against their common enemy. In late July, Churchill agreed that “we are also studying as a further development the basing of some British fighter air squadrons on Murmansk... some (aircraft) of which could be flown off carriers and others crated.”

As a consequence, Operation Dervish, the first arctic convoy, was conceived. On 12 August, seven commercial vessels sailed from Liverpool with the Union-Castle liner, SS Llanstephan Castle, carrying some 550 men of RAF 151 Wing, comprising 81 and 134 Squadrons, and 15 crated Hurricanes for assembly. There was also a convoy of eleven Royal Navy warships which included the fleet carrier HMS Argus with 24 Hurricanes ready to fly. The role of 151 Wing was to train the Russians in flying and maintaining the ’planes, then hand them over and return home. This was the first part of an agreement which would ultimately provide them with more than 3,000 aircraft throughout the war.

'Tim' Elkington was a pilot with 134 Squadron

I left the RAF College at Cranwell for No 1 Squadron, Northolt, in July 1940, having had elementary training on biplanes - Hawker Harts and Hinds. Then after 15 hours’ familiarisation on the Hurricane before going operational, I was on patrol over the Channel.

A few months later, having survived the Battle of Britain with only one unfortunate incident, I was enjoying life with 601 Squadron at Manston - interception patrols, search and rescue escort, and later, sweeps over France.

Too good to last, and in July 1941 came a posting for overseas. At Leconfield on 29 July speculation was ended: we - the re-formed 81 and 134 Squadrons - were to fly off an aircraft carrier into Russia.

Aboard HMS Argus on 18 August, the First Sea Lord gave a briefing informing us that we, as 151 Wing, had been promised by Churchill in response to Stalin’s demands for support. Our role was to be “the defence of the naval base of Murmansk and co-operation with the Soviet forces in the Murmansk area”. We were to instruct the Soviet authorities in the operation and maintenance of our aircraft and ground equipment, which was then to be handed over to them.

And so it was that we became part of the first ever convoy to Russia, together with merchantmen carrying the rest of the Wing and crated Hurricanes, escorted by HMS Victorious, Shropshire, Punjabi, Electra, Somali and Matabele.

Whilst in Scapa Flow outbound from 20 August, we received typical naval hospitality on several of the ships anchored there. Mindful of events a few months later, it is painful to reflect on those present - HMS Prince of Wales, Repulse, King George V, Victorious, Furious, Malaya, Sheffield and London.

On 30 August, we finally sailed for Iceland, together with a convoy for North America, with Sunderland and Catalina escorts. For a few days we were down to 7 knots in thick fog. On 3 September, the weather cleared and I have a note that Martlets from Victorious ‘got’ a Dornier Do17. One Fulmar was lost in the engagement. There were more days of thick fog.

Then came the day for flying off - 7 September. Thankfully, the fog lifted and we re-read our instructions. Although Hurricanes had been flown off before, it looked like being a close call. Flights of six aircraft were to be flown off at a time. The Hurricane was 31 ft long, so two lines of three aircraft would take at least 65 ft. The flight deck was 470 ft. The unstick distance of the Hurricane was

396 ft, assuming wind over the deck of 22 knots. Given that we had only just left a fogbank, it seemed unlikely that there would be significant natural wind, so it remained for Argus to sail flat out at 20.75 knots, leaving the difference to the Gods! In fact, one of the first aircraft hit the accelerator ramp in the bow and had to belly land in Russia.

We were airborne by 0600 hours and, because our compasses were unreliable in that area, some 200 miles north of Murmansk, we had to set course by passing over the carrier, then a positioned destroyer, and keep going.

After over-flying miles of desolate tundra, we landed at Vaenga, a vast expanse of pot-holed sand which later became a soggy mess. Breakfast, however, was more welcoming - caviar, smoked salmon, Finnish ham, wine and champagne.

The ensuing diet is well documented in Hubert Griffith’s book, RAF in Russia.

The weather was not helpful. Some days were balmy - but so many were unflyable. In the first month, we were unfortunate, as a squadron, to miss out on engagement with the enemy. Apart from reconnaissance, our first real work did not come until 17 September, with three patrols on that day over the front line. Even then we saw nothing but flak, directed both at us and the bombers we were escorting. A few days later, close to Petsamo, one Petlyakov Pe2 was hit and crashed in flames after the crew had jettisoned their bombs and bailed out. Their bombs came close to hitting the ships that were firing.

October opened with attacks on our airfield. No advanced warning system existed. On the first occasion, some 20 Ju88s dropped their load and we took off to intercept through a hail of bullets, dodging the bomb craters. One 81 Sqn pilot, whose engine was stopped by a blast on take-off, was then blown off the wing by another blast. Of 134 Squadron, I was first away and managed to catch up with them at 7,000 ft.

My No 2 joined me and we damaged one Ju88 which later failed to reach home. The weather was now closing in and our efforts were devoted more to the conversion of the Russian pilots, who seemed oblivious of fog, snow and ice, and the instruction of their technicians. We watched with disbelief as a protégé attempted his third approach in dense fog. Came the time for return home, and the most testing time of the expedition, for me at least, began.

On 16 November, I was put in charge of an advance party of seven officers and 60 airmen, which I had to lead in deep snow, in virtual night, down the 10 miles or so of treacherous track to Rosta oiling jetty. We knew when we reached our destination, at 5.00 pm, when all our kit became black with oil. Our only casualty was one airman with a broken arm.

We waited there six hours for the fleet minesweepers we had to board for the voyage to Archangel - HMS Hussar, in our case, HMS Gossamer and Speedy, only to find that they had docked at a different jetty. (If anything suggests that we had a tough assignment, one should read their sea logs!) Eventually bed, without food for 14 hours, at 2.00 am.

Next day, sailed up to Polyarny and a drink on board the submarine Seawolf before she left on patrol. Transferring to an icebreaker, captained by a very large lady, we struggled through 6" deep ice for the last 20 miles into Archangel. We were passed by one merchantman loaded with crated Hurricanes and tanks. On the icebreaker, I made the acquaintance of General Gromov - the pre-war long distance flyer.

On 24 November, we transferred to MV Empire Baffin, a 10,000 ton cargo ship. Despite the icebreakers, moving yards at a time, it was not until four days later that we were steaming past the Gorodetski light and into the open sea. We were held to 7.5 knots for the Russian boats with us - their first convoy to the UK. It was only then that we found the two Estonian stowaways who had crossed the ice at night to board us.

HMS Kenya joined us on the 29th, with most of the Wing personnel on board. The following day, we had to heave to in gales and heavy seas. A lifeboat was washed away, and slag ballast was shifting on the deck. We had to rope ourselves into our bunks at night, with no chance of sleep. Everything was heavy with frozen spray which had to be constantly chipped off with shovels. We were sleeping in our clothes in case we had to get Vic Berg to the lifeboats. Vic, one of our Flight Commanders, was in full plaster following a terrible crash in which two airmen died. On 1 December, we were attacked by a U-boat. The destroyers depth charged - thankfully no casualties, but an outgoing convoy later lost several ships. Again, we had to help the crew to relocate the shifting ballast.

Three days later, our engines cut out with propellers racing in the heavy seas, and our steering gear was damaged. Still semi-dusk all day, and several mines were seen - one uncomfortably close.

(The DVD, Hurricanes to Murmansk, gives an idea, however brief, of the conditions encountered later by so many for so long.)

“Of all the convoy routes of the Second World War, the most dangerous was the Arctic course, followed by ships carrying supplies to the Russian ports of Murmansk and Archangel. Forced to follow the coast line of Nazi-occupied Norway, the convoys were not only threatened by submarines but subject to devastating attacks by land-based aircraft, submarines and surface vessels from Norwegian ports. These hazards were compounded by the brutal and often unpredictable weather. Finally, throughout the Arctic summer, these convoys were forced to tread their way north fully exposed in 24 hours of daylight.”

We were hugely fortunate to have sailed both ways unscathed, before the enemy took the Arctic convoys more seriously.

After passing the breathtaking scenery of Iceland, on 16 December we finally arrived back in Scotland and home!!

Bookcover Force Benedict Churchill's scret mission to save Stalinby Eric Carter and Antony Loveless

THE last surviving member of a secret RAF squadron who helped save Russia from defeat by Nazi Germany has finally revealed the truth about his wartime heroics.

Eric Carter was a 21 year-old fighter pilot in 1941 when he boarded a blacked-out train in Hull with his 81 Squadron and taken to Liverpool.

The young airmen were then ushered on to a waiting ship and set sail for the open seas, still none the wiser about their destination.

Rumours within the squadron suggested they could be heading for Africa – but they soon discovered they would not need any warm weather gear.

Eric was part of Force Benedict, a clandestine operation to save the strategically vital Russian port of Murmansk.

It was being targeted by the Nazis who were marching relentlessly towards Moscow.

The mission to protect the port and train Russian fighter pilots was top secret because Stalin did not want the world to know he needed British help to defeat the invading Germans.

And such was the secrecy surrounding the ultimately successful operation, that it was largely forgotten for nearly 70 years.

That is until the chance discovery earlier this year of a medal awarded to Force Benedict's Wing Commander, Group Captain Henry Neville Gynes Ramsbottom-Isherwood.

He was one of only four non-Russians awarded the nation's highest military award, the Order of Lenin, which was sold at auction in Sothebys this week for £46,000.

Eric, now 89 and living in Chaddesley Corbett, Worcestershire, revealed how he and his comrades were plunged into a grim battle of life and death in the skies above the port on the edge of the Arctic circle.

He said: Force Benedict was a very well kept secret.

Stalin did not want his people to know that he had asked the West for help and we were threatened with a court martial if we said anything.

I was young and must have been mad, but perhaps we were just a tougher generation. I knew the average lifespan in the air was just 15 minutes but I was determined to volunteer after hearing the atrocities the Germans had carried out on the Russians.

Eric had joined the RAF in 1939 and was initially posted to the famous 615 Squadron who were recuperating in Wales following the Battle of Britain in 1940.

He served with them for a year, defending the skies over Liverpool and Manchester, before being transferred to 81 Squadron. Alongside 134 Squadron, they made up 151 Wing which was sent to save Murmansk.

Eric said: Murmansk was a pivotal point in the war. It was Russia's Battle of Britain, the battle for their very survival, and we had to hold on to the port at all costs.

Our job was to escort Russian bombers and fight off the German planes. We went on 60-odd missions and never lost one bomber.

But we were only 10 miles from the German base.

Their General repeatedly asked Hitler for more men so they could overun our airfield but he refused, so we got lucky there.

Life in the freezing under-siege city was tough and the threat of death constantly stalked the British pilots – with German bombers above and trigger-happy Russians on the ground.

Eric said: Murmansk was like Beirut, it was all rubble.

And the Russians soldiers did not bother to ask who you were, they just killed you on sight. So we were issued with special passes and had to hold them in front of us as we walked anywhere or else we would have been shot.

It was minus 40 most of the time. Our aircraft and transport vehicles had to be started up every 20 minutes to prevent them from freezing for good.

And life was so cheap out there.

Labourers working on the airfield would sometimes freeze to death after a night drinking and in the morning they would be just scooped up and put in the back of a truck.

But that helped build the strongest camaraderie with your pals because that was all we had. You depended on them for your life and they were all that you lived for.

Yet we never thought Murmansk was a hopeless cause, never considered defeat and never contemplated that Britain might be invaded if we lost.

We were determined to win and that's what we did.

When you were up in the air you were nearly always in trouble, but Murmansk was the key to everything at that point so we just had to survive.

We used to fly in pairs to cover each other and shot down our fair share of Luftwaffe, but the Germans gave us a very hard time.

Yet although we lost a pilot on the first day, we only lost one other during our time there.

Wing 151 carried out 365 sorties during a four-month stay in Murmansk, shooting down 11 Messerschmitt fighters and three Junker 88 bombers before handing the secured port back to the Russians on October 13, 1941.

By then the deep snows had begun falling and the German army was set to stall within sight of Moscow. It was the beginning of the end of Hitler's invasion of Russia – and the turning point of the Second World War.

Eric and his comrades returned to Britain without fanfare after the operation.

He married his wife Phyllis, who he described as 'wonderful wife and mother', while on leave in 1943, before being posted to Burma for the remainder of the war, flying Spitfires and supply missions in Dakotas from Rangoon to Calcutta.

His beloved wife passed away four years ago, after 62 years of marriage.

But the people of Murmansk have never forgotten Eric's bravery and he has been invited back to the city many times in recent years where he is still feted as a hero.

The Russian Government has never forgotten what we did for them, said Eric, who is the last survivor of 81 Squadron – and possibly the last remaining member of Force Benedict.

Me and my wife were invited to the Russian Embassy in London during the 1980s for a ceremony of remembrance with the Ambassador.

It was a funny occasion and he had a big rant about Margaret Thatcher, I didn't know where to put my face.

And I have been repeatedly asked back to Murmansk to remember what we did for them.

The Russians think a lot more of their war veterans then we do in Britain and they have really looked after me every time I have been over there. They even let me go on board one of their nuclear submarines and how many British people can say they have done that?

A lot of my pals died during the war and I'm the only one left now.

I hope our sacrifice and the freedom people enjoy now means it was worth it.

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

-AFC-DFC-Order-of-Lenin-March-1942-01.jpg)