Operations Against England

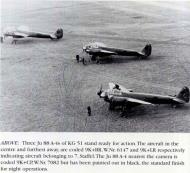

The ground organisation and final stations for the units of Luftflotte 2 under Kesselring (Brussels) and Luftflotte 3 under Sperrle (Paris) remained for a time in a bad state, with all the usual need for improvisation. Along the Loire, around Paris, past Brussels and as far east as Amsterdam the bomber Geschwadern lay poised, while the dive-bomber and fighter Geschwadern were focused round Le Havre and Calais, nearer to the Channel because of their shorter range. KG 51 was in Fliegerkorps V under Ritter von Greim, together with KG 54 (Lt Col Hoelne, Evreux) and KG 55 (Colonel Stoeckl, Chartres). The Korps operations center was at Villacoublay.

Historical analysis differ over the phasing of events in the Battle of Britain; eight different versions are known to the author. From these he has chosen the account of the Swiss Dr Theo Weber, which in his view comes closest to the course of events as a whole.

The Contact Phase started at the beginning of July 1940 with armed photo-reconnaissance attacks on merchant shipping and harassing attacks on British port installations. These operations were conducted under orders at Luftflotte level, since no orders had yet emerged from the High Command. Bombing raids in force on the island Kingdom began on July 10th with the aim of drawing British Fighter Command to battle. Ill Gruppe flew only three sorties with its new Ju 88 A-1's, these against targets in the Portsmouth area, which lay hidden under heavy cloud and rain squalls.

In occupied France the newly converted crews continued intensive training on their new aircraft. They familiarized themselves with the dive-bombing technique, flew bombing practices to improve accuracy, exercised in cooperation with the pathfinder unit Kampfgruppe 100, and gave the ground staff a chance to work up the handling, arming, care and servicing of the Junkers. A few well-trained pilot-observers flew far and wide to find suitable diversion fields. Slowly they got used to the new area of operations. Up to the end of July they had taken part in only three major operations, the last one on July 29th being a mass night attack on armament and aero-engine plants and refineries in the Liverpool and

Southampton areas.

Main Combat Phase I began on August 8th, 1940, ‘Eagle Day’, after grand-tactical aims had at last been laid down in Air Force Command Directive No 17. The Royal Air Force was to be fought to a standstill as soon as possible, by the engagement of a wide variety of targets including armament works, the new and surprisingly effective radar stations, air bases and army camps. Terror raids were expressly forbidden.

At the start the weather impeded large-scale air operations. The majority of pilots in both our own and other Geschwardern were not yet sufficiently familiar with night operations, and there was no time or opportunity for training. For the attack of key targets, such as British aircraft and engine factories, special crews known as ‘destruction crews’ were designated. For this dangerous, often foolhardy task they received, over and above the usual flying duty pay, special danger money of 400 Reichsmarks a lot of money at that time. These ‘destruction crews’ were drawn from crews outstanding in skill and achievement of each bomber wing. They were given full written briefs on their targets, but were not tied down to times or particular tactics or their unit operational procedures. They were directly responsible to Fliegerkorps for putting the targets out of action. The captain of a crew made his own assessment of weather and the air situation and finally decided for himself when and under what conditions he should strike. It would be superfluous to enlarge on the dangers of these operations; one needs only to consider that these crews flew their missions without fighter escort.

Lieut Dr Karl-Heinz Stahl and his crew, Schroeter, Noemeyer and Motes, carried out one of these special tasks on August 23rd, 1940. The target was the Test Centre at Farnborough. The account that follows has been written with the help of notes made by war correspondent Wolfgang Kuechler:

‘The clouds hung low over our French operational air field at Villacoublay, so low that their fringes almost touched the ground. The crews sat around in a black mood. They had counted on having another little trip to England; and now it had been called off because of the weather. But they all stayed round the flight dispersal area. Mightn’t there be something on after all? They were right. Only two minutes or so had gone by when the adjutant rushed out of the ops room waving a paper to say that one crew was to take off for a solo blind-flying raid. The target was the aircraft test centre at Farnborough. In a flash everyone sat up and took notice; they looked expectantly at their squadron commander, Captain Kurt von Greifr, who had to take the decision. After a long pause his eyes came to rest on the wiry little reserve lieutenant, Dr Karl-Heinz Stahl, and minutes later 9K +ID - 'Ida Henry' was airborne with a full bomb- load.

Shortly after take-off Lieut Stahl climbed into the cloud. The Ju 88’s engines hummed away monotonously; steadily it gained height. Once they broke out of the top of the cloud, a fantastic view awaited these men. The sea of cloud constantly surged and bubbled, but the four lonely men in Ida Henry had little time or leisure in which to look at this drama which never ceases to stir an airman’s heart. They had to concentrate on the task in hand. The French coast lay far astern of the German aircraft; soon they must be over England. The clouds prevented their seeing the ground but on the other hand it stopped the British fighters coming up after the Junkers; that was some comfort.

Lieut Stahl looks at the clock on the instrument panel and pulls his large-scale navigation map of England a bit nearer to have a look at it. Another ten minutes and we’ll be there! The tension mounts. Will the British Flak be alert? Senior Warrant Officer Schroeter, the observer/' gunner, casts a quick but careful eye over the bomb-release mechanism. The rear gunner, LAC Motes, hunches tensely over his machine-gun. Now we’re all ready to go! Ida Henry plunges down through a gap in the clouds. To everyone’s astonishment they see below not only the target, Farnborough airfield, but also forty British Spitfires alerted by the radar stations, flying in a tight circle to cover it!

As a welcome some light A A sends up a first, ill-aimed burst. A vic of Spitfires curves in to engage the single solitary bomber. Grimly and calmly, Lieut Stahl makes his run-in, so that Senior Warrant Officer Schroeter can get the target well in his sight. The first bomb is away; and then there are three more little jerks as the others go.

Meanwhile eight Spitfires have dived on Ida Henry. They come in from both sides. Warrant Officer Noemeyer lets fly at them with his first machine-gun bursts. An Englishman fires—spot on target. The bullets rattle into the machine and splinter. A second burst whistles just over Senior Warrant Officer Schroeter’s head; luckily he’s still lying on his stomach over the bomb sight and so escapes death. Warrant Officer Noemeyer is slightly wounded after the British onslaught, but that doesn’t stop him answering the Spitfire, which has closed right up to 100 feet, in kind. A hit! The Spitfire rears up, then turns slowly on its side. A burst from LAC Motes does the rest; with a dark plume of smoke it plunges downwards. There’s another fighter—up there to port! Lieut Stahl sees what the enemy means to do and with a burst of throttle turns right in on his attacker. Without getting a shot in, the Englishman flashes past, only about five yards clear of the German machine’s rudder. It took full throttle and a bit of hard work to get ‘Ida Henry’ up into the cover of the clouds. Safety at last. But what a state the old crate’s in! Instrument panel ripped away, the electrics shot to pieces, the radio smashed and the intercom out of action. The crew is thankful enough still to be able to fly after getting away from that little party.

But the danger is not over yet. After about three minutes flying blind in the cloud the starboard engine suddenly begins to rattle. Lieut Stahl feathers it, and on they fly on one engine. The pilot pushes his foot through the floor trying to stay on course. Soon he gets cramp in his leg and Senior Warrant Officer Schroeter has to get a foot on the rudder pedal to help him. So it is that, slowly, steadily losing height and steering on the emergency compass, they zig-zag their way towards the French coast. And it’s high time they landed—they’re nearly out of fuel. Suddenly the port engine rattles and cuts out. Silent as a forest. For the last time Lieut Stahl summons up his last ounce of strength and concentrates on making a belly landing—a risky business at the best of times—near Caen. Softly and surely the machine swoops in with no noise but the rush of air, and sits itself gently down. Straight-away every kind of help is rushed to the crew; and ten minutes later they are even being congratulated by the Commanding General, who happens to be in Caen and has watched ‘Ida Henry’s’ forced landing.’

The British radar stations, especially those on the Isle of Wight, had to be taken out to allow the German bomber to fly in with less interference over the English ports. Trials Gruppe 210 (Rubensdoeffer) led the attack. At about 1100hrs on August 12th, 1940, KG 51 with almost 100 Ju 88s, ZG 2 and ZG 76 (120 Me 110s) and JG 53 with 25 Me 109s assembled over the French coast near Cherbourg. Colonel Dr Fisser, commander of KG 51 and appointed to command this mass formation, waited impatiently for the flights to close up. The main target was Portsmouth Dockyard. Carrying SC250 (5501b) bombs and some SC1000 (1 ton) blockbusters, the Staff el leaders headed for their target at 17,000 feet.

On the flight in fighter activity remained slight. It was not until 11:45hrs that they were picked up by the British radar station at Poling. A barrage of 50 balloons came up, suddenly rising to 6,000 feet and heralding an attack. The German fighters tried to draw the British out to battle. The Ju 88 formation split, 70 aircraft turning for Portsmouth. The harbour, the main station, fuel tank depots and small ships were repeatedly engaged from level flight and by dive-bombing. Almost at the same moment 20 Junkers started to attack the radar station at Ventnor, on the southeast tip of the Isle of Wight.

Flak began to come up. At 13,000 feet the shooting was indifferent, no more than harassing; but at 7,000 feet and below it was dense and well- placed. More and more bombers broke away, hit by Flak or fighters. Thirteen crews from KG 51 failed to return; At 12.30hrs a Hurricane of No 213 Squadron shot the commander’s machine down. Colonel Dr Fisser was killed; his observer, 1st Lieut Luederitz, and Lieut Schad were severely wounded and taken prisoner.

When the formation turned away, Spitfires, Hurricanes and Defiants swooped like hawks on the returning aircraft. Apart from the 13 machines shot down, almost every aircraft was hit by Flak or machine- gun fire, in some cases seriously. Major Marienfeld, commanding III Gruppe, and 1st Lieut Lange of 9 Staffel shot down one Spitfire each. Lieut Unrau and his crew, in 9K+HL, were pursued over the Channel by three Hurricanes. His operator, Warrant Officer Winter, shot one down. One engine of the Junkers was put out and they only just managed to reach the French coast. There the second engine seized and it was by sheer good flying that they achieved a belly landing right on the edge of the shelving coast. They got out unhurt and counted 180 hits on their machine.

Thanks to the early warning provided by their radar stations, British Fighter Command was able to deploy their forces economically but to good effect. On the German side an attempt was made to counter this advantage by raids deeper into the area of operations and by engaging widely dispersed targets. In this way it was hoped to commit all four British Fighter Groups at once. On August 16th the Wing attacked airfields—I Gruppe on Redhill, II Gruppe on Brooklands and III Gruppe on Gatwick; thick fog stopped III Gruppe aiming their bombs.

A heavy fighter Gruppe from ZG 26 flew escort from St Aubin, and on the way back engaged opportunity targets in the Eastbourne—Horsham —Worthing area. For once this daylight raid went through without loss. Up to August 25th daylight raids were made on various airfields and on Portsmouth, which we were getting to know fairly well.

Some of the SC250 (5501b) bombs dropped had the new LZZ delay fuse, which set them off hours or days after they were dropped. The new 5001b Flam incendiaries also proved effective.

A few crews had an unpleasant encounter with the ‘brook’, as the English Channel was condescendingly called. Some could count themselves lucky at being picked up by the Sea Rescue Service.

From this point on fierce engagements at great height became a regular feature as the bombers winged their way doggedly on. Forewarned, the enemy fighters were seldom caught on the ground; they would take off as soon as approaching aircraft were reported, to try as far as possible to catch the German machines on the way in before they dropped their bombs. In the second half of August the Battle of Britain had reached a critical stage for the British. From August 8th on, the Royal Air Force lost 1,115 fighters and 92 bombers against German losses of only 254 fighters and 215 bombers. The aim of achieving air superiority over the island seemed to be within the German grasp. But at the end of August 1940 the bombing tactics changed.

From then on night raids were flown by individual aircraft. At two minute intervals, usually taking off from midnight onwards, all crews who had been trained for night operations—and this was by no means all of them—attacked Liverpool, Birmingham, Manchester and, from September 8th onwards, London. The RAF’s night fighter defence, later to prove so formidable, was not particularly effective at this time.

On one of the last missions against Liverpool and Birkenhead, five minutes after its first run, a crew suddenly noticed a flare-up of light from the ground. One after the other, over an area about 3 miles long and 500 or 600 yards wide, innumerable lights appeared; they were supposed to represent a town on fire. The large-scale dummy fire set up by the British south of Liverpool on August 30th, 1940, for instance, simulated burning docks. Many German crews fell for these skilful deceptive measures and dropped their bombs—on the burning hills of Wales.

As a result of the relatively high losses suffered earlier on, new, freshly-trained young crews quickly started to appear in the Geschwader. Naturally they were not put straight on to operations. The usual operational training within the bomber Staffeln put a heavy load on those who were already flying missions every day. So in August 1940 Geschwader Headquarters gave Captain Ritter the job of setting up a reinforcement Staff el at Orly, which provided operational training for the newcomers. Night flying was a particular focus of attention. The 7th Airfield Support Company detached a technical platoon under Warrant Officer Weiss to look after their machines.

From the main fighter battle there developed a new phase of the bombing war. On September 3rd, 1940 Goering called the force commanders to the Hague, to discuss a change of targets with them. In his view little advantage was to be had from further attacks on enemy airfields, fighter operations centres, radar stations and aircraft factories. Instead, military targets in and around London would be bombed, on the grounds that the British would only commit their final reserves to protect such a vital target. With the first night raid by German bombers on targets in London, on the night of September 5th, 1940, the Battle of Britain entered a completely new stage; German air operations against the British economic potential had begun.

If the German air operations of Main Battle Phase I had essentially been conducted in support of naval planning for an invasion of England, from September 6th onwards no further connection with the plans for Operation Sealion was discernible. This was the beginning of Main Battle Phase II, which lasted until May 10th, 1941. Goering had ordered the opening of operations against the economy at the very point in time when the British fighter arm, in particular its ground organisation and reinforcement situation, was at a nadir and a short continuation of the

Operations Against England 41 air offensive against the British fighter infrastructure would have had very serious consequences for Fighter Command.

It is no exaggeration to describe this second phase of the battle as a strategic one. On the afternoon of September 7th Goering stood with Kesselring and Loerzer near Cap Gris Nez on the Channel coast and watched the bomber and fighter formations thunder away over his head. According to radio commentators who were there, he had ‘taken over personal command of the Luftwaffe in the struggle against England’! 625 bombers in all flew on London, starting in the afternoon and going on late into the night.

About 60 bombers from KG 51 made raids on London that night, from about 13,000 feet. From a long way off one could see the sky glowing with the fires of the hard-hit city. South of London they found some realistic deception sites. Oddly enough there was very little trouble from Flak. But this state of affairs was soon going to change.

Night after night up to 300 bombers raided London, and the city had no rest. The night-fighters, mainly Blenheim’s, became more noticeable and played on the bomber crews’ nerves though they caused no losses in KG 51. During this time repeated diversionary raids were being carried out on Plymouth, Portland or Portsmouth; but the focal point of the operations remained London.

The occasional day sorties that had to be flown without fighter escort were nerveracking in the extreme. Quite often up to twenty Spitfires, engaged in a blocking action off the coast, would swoop down on the formation, which always hoped it could take cover in the clouds and ‘softly and silently vanish away’. This trick usually served to shake off the enemy fighters, which was just as well. From October onwards KG 51 flew only by night, or took off so late in autumn and winter dusk that it was dark when it arrived over the target. There was of course no possibility of surprise; the excellent British radar stations picked up the formation almost as soon as it cleared the French coast, and kept track of it with ‘the eye that sees through fog and darkness’. By day the fighter-bomber flights of the fighter force, ironically known as ‘light Kesselrings’, slipped through to their targets; but despite their losses they could inflict no more than a pinprick.

The operations against London remained the centre of effort up to November 14th, but thanks to the tactic of attacking by night there were no significant losses apart from crashes or forced landings on French soil.

III Gruppe alone flew a total of 295 sorties in 49 operations. Only nine machines failed to carry out their task, because of weather or technical failures, mainly damaged engines. At a Geschwader parade held in the Zeppelin hangar at Orly on November 12th, 1940, Field Marshal Hugo Sperrle decorated battle-hardened men of KG 51 with the Iron Cross

First or Second Class; many of them stood heavily bandaged, in witness of wounds received in the air fighting.

The target on the night of November 14th was the city of Coventry; the bombers flew in using the Knickebein navigational aid, but did not need it because the glow of the burning city showed them the way. The mass attack with 500 tons of high explosive and 30,000 incendiary bombs caused considerable devastation.

During November the Luftwaffe delivered further heavy night attacks, on the same pattern as that against Coventry but to less effect, on Birmingham (November 19/20), Southampton (November 23/24), Bristol (November 24/25), and Plymouth and Liverpool (both November 28/29). Along with this, raids on London continued at a reduced scale. In November alone a total of 6,650 tons of bombs were dropped on English cities, and these attacks continued into December.

KGr 100 and KG 26 often flew in the pathfinder role, and used flares to lay paths, as they were called, in the target area. These could be seen from a long way off. For in more and more instances had it been found that the radio beacons were being subjected to intensive interference and were useless for navigation. The British were getting cleverer and cleverer at breaking in to our radio-navigation systems.

The Geschwader was able to spend New Year’s Eve in Paris released from operations, as the bad weather was still preventing mass attacks. In January the effective disruption of the radio-navigation systems, and the activities of British radar-controlled night fighters, finally forced the Luftwaffe to switch attacks from industrial centres deep in England to coastal towns, which the bomber crews could find—even at night —without radio aids. This proved to be a decisive success for the British air defence.

In his combat report written after the operation in the night of January 10th, 1941,1st Lieut Kuechle wrote:

Combat Report by 1st Lieut Kuechle—Attack by Night Fighters. Mission of night of January 10/llth, 1941.

We could see the fires in Portsmouth even before we reached Fecamp. We made our run from southeast to northwest. After releasing our bombs at 21.08hrs from altitude 15,500 feet we turned to port on to compass heading 140° for Fecamp. We were flying at 2,100rpm with 11.5 pounds of boost. Over the target there was broken cloud cover at about 3,500 feet, while the Isle of Wight was clear and could easily be seen in the moonlight. Between Portsmouth and the Isle of W'ight, about 2—4 minutes after bomb release, the operator reported a night-fighter approaching from starboard at about 90° to our own course. Just before reaching us it pulled up, curved to port and swung on to our tail.

After the night-fighter’s first run-in, during which it did not fire, our pilot started to descend at about 600 feet per minute, leaving the autopilot on. Fire was opened at about 100 yards, almost simultaneously by our gunner and the night-fighter. At this the pilot increased the rate of descent and when hits were heard, he dived still more sharply. At 14,000 feet the airspeed indicator was showing 280mph. While in this steep dive the pilot saw the night-fighter’s tracer above his aircraft, on his course. He therefore swung off sharply to port. The night-fighter pulled up to port and disappeared.

Immediately there was another attack, this time from below on the starboard side. It was probably a different night-fighter, for the first one could hardly have got into position for a second attack. With the autopilot off and diving steeply, at an indicated airspeed 310mph at 2,300rpm, we turned to starboard with full deflection on the turn indicator onto a southerly course. The flight engineer fired off half a drum of ammunition, and the fighter pulled away.

The radio operator saw a night-fighter above us to port, but it made no move to attack.

Using the autopilot and zigzagging constantly between 180 and 100 degrees, we flew towards Fecamp. We had dropped to altitude 6,500 feet. Since the starboard oil tank was showing empty and the starboard engine was running unevenly, we gained height over the Channel. No one in the crew was wounded. As the hydraulic guages were not reading, the pilot selected flaps and the undercarriage down to test the system; this showed that the main system was unserviceable. We radioed ‘Undercarriage damaged, will land last’.

At 22.50hrs, after the undercarriage and flaps had been lowered on the emergency system, we came in to land. On touch-down the machine tried to swing to starboard, but this was checked by full port rudder and brakes. Since it was almost out of control and had such a list to starboard as to suggest that the undercarriage had buckled, the pilot ordered the cockpit hood jettisoned. The aircraft turned slightly to starboard as it drew to a halt. As soon as it stopped, the engines were cut and the electrics switched off, and the crew clambered out.

The aircraft had received 38 hits during the two attacks. The starboard tyre had been shot to pieces. Eight or ten large entry holes indicated the use of explosive rounds from cannon.

(signed) Kuechle

1st Lieut, Headquarters Flight Commander

The Geschwader did not take part in the last major operations against England. It flew its last raid in this theatre on March 27th, 1941 against Cowley near Oxford. For the last time it had a taste of the stinging, accurate British Flak.

Review of Operations and Losses

Before moving on, a review of the operations against England from June 20th, 1940 to March 31st, 1941 is called for. The data quoted are taken from the III KG/51 war diary, and may be considered representative of all the bomber units involved.

The German Air Force lost 2,265 aircraft, of which 25% were fighters and 35% bombers. These losses appear to have been made good by new production, though it must be questioned whether production kept pace with the enemy’s technical achievements. The really damaging losses were however in pilots and crews who had been thoroughly trained in peacetime. These amounted to 3,363 killed and 2,117 wounded, as well as 2,641 airmen who were either missing or taken prisoner by the British. Most of KG 5 Vs dead found their last resting-place in the cemetery at Meaux.

From this point on the German Air Force came to have only secondary importance as an independent arm of the service. Throughout the rest of World War II no further attempt was made to use it for independent operations at strategic or grand-tactical level. Even in a supporting role to the Army and Navy it was no longer able to force a decision at really key points. The limits of German power were revealed, and the time of the blitzkrieg campaigns was past.

KG 51 AIRCRAFT LOSSES (OPERATIONS AGAINST ENGLAND)

Period 17 1940 — 31st Oct 1940 (four months only)

On one day, August 12th, 1940 when the commander Colonel Dr Fisser was killed, aircraft losses amounted to:

Headquarters — 1(100%)

III Gruppe — 4 (100%), 1 (30%), 1 (15%)

I Gruppe — 3 (100%), 1 (30%)

II Gruppe — 2(100%)

Note. Aircraft losses were categorised according to the degree of damage.

100% Total loss

III Operations Against England 1

Review of Operations and Losses 2

systems (e.g. hydraulics).

25-39% Damage calling for a complete in-unit inspection.

10—24% Moderate damage from enemy fire, remediable by minor repairs.

under 10% Light damage, repairable by ground crew.

III Gruppe, Kampfgeschwader 51 Station Wiener Neustadt

March 31st, 1941

Review of Operations against England from 20th June 1940 to 31st March 1941

1,112 missions, 648 sorties, including:

III Operations Against England 1

Review of Operations and Losses 2

7

2 Flying hours—1,603hrs 3 lmin.

3 Miles flown—26,053,162nm.

4 Bombs dropped—627 tons 6001bs.

Losses: KG 51 AIRCRAFT LOSSES (OPERATIONS AGAINST ENGLAND)

KG 51 AIRCRAFT LOSSES (OPERATIONS AGAINST ENGLAND)

KG 51 AIRCRAFT LOSSES (OPERATIONS AGAINST ENGLAND)

| Date |

Aircraft Code |

Werk Nr |

Location and remarks |

| 13th July 1940 |

9K+CR |

7074 |

Rouen Belly- |

| 30th July 1940 |

9K+ER |

7081 |

Nogent le Crashed on landing, 20% |

| 31st July 1940 |

9K+FT |

7068 |

Rotron Orly 1oo% Belly-landed |

| 9th Aug 1940 |

9K+GS |

7052 |

Mondesir crashed on landing, 35% |

| 9th Aug 1940 |

9K+DD |

5064 |

Mondesir Crashed on take-off, 75% |

| 10th Aug 1940 |

9K+JR |

7071 |

Beauvais take-off, 50% Damaged |

| 12th Aug 1940 |

9K+ED |

7073 |

? Fighter Attack |

| 12th Aug 1940 |

9K+AT |

5042 |

le Havre Forced landing, 70% |

| 12th Aug 1940 |

9K+KT |

7091 |

Portsmouth Missing, |

| 12th Aug 1940 |

9K+FS |

5072 |

Portsmouth 100% Shot down, |

| 12th Aug 1940 |

9K+BS |

4078 |

Portsmouth 100% ? 100% |

| 12th Aug 1940 |

9K+AS |

5063 |

Portsmouth ? 100% |

| 19th Aug 1940 |

9K+FR |

7069 |

Little Missing |

| 25th Aug 1940 |

9K+BR |

7072 |

Rissington Portsmouth 100% |

| 30th Aug 1940 |

9K+DS |

7076 |

Mondesir 70% damage on landing |

| 7th Sep 1940 |

9K+CD |

2167 |

Villaroche 15% damage on landing |

| 12th Sep 1940 |

9K+DT |

5053 |

Crashed London 2 crew KIA |

| 20th Sep 1940 |

9K+MR |

7092 |

Lille forced landed 45% |

| 25th Sep 1940 |

9K+FR |

4144 |

Evreaux 100% Crashed 4 crew kiled |

| 27th Sep 1940 |

9K+IR |

2174 |

Pusscay 100% Crashed 4 crew kiled |

| 27th Sep 1940 |

9K+BR |

6153 |

Oisonville 100% Crashed 4 crew kiled |

| 10th Oct 1940 |

9K+CD |

2104 |

Mondesir 100% Damage on landing 25% |

| 10th Oct 1940 |

9K+HS |

299 |

Crashed London 4 POW |

| 12th Oct 1940 |

9K+DR |

7075 |

Mondesir 100% Crashed on take-off 3 crew wounded 1 killed |

| 28th Oct 1940 |

9K+MR |

8040 |

Crashed London 100% 4 MIA |

| 6th Nov 1940 |

9K+KS |

5070 |

Crashed London 100% 4 MIA |

| 18th Nov 1940 |

9K+GR |

7082 |

Villeneuve 100% crashed 4 crew kiled |

| 18th Nov 1940 |

9K+AT |

7054 |

Bretigny crashed 100% crew okay |

| 20th Nov 1940 |

9K+GT |

7062 |

Bretigny crashed on landing, 80% crew okay |

| 31st Nov 1940 |

9K+AB |

5050 |

Bretigny damaged on landing, 80% crew okay |

| 31st Nov 1940 |

9K+FS |

3189 |

Bretigny damaged on landing, 20% |

| 21st Dec 1940 |

9K+FT |

296 |

Bretigny Crashed on landing, 15% 4 crew kiled |

| 30th Dec 1940 |

9K+LR |

5045 |

Bretigny Crashed on - approach, 100% 1 crew wounded 3 crew kiled |

| 15th Mar 1941 |

9K+BS |

7119 |

Bovoux Forced - landing, 60% 1 crew wounded 3 crew kiled |

| 15th Mar 1941 |

9K+HT |

2271 |

Bonneville Crashed on landing, 40% 4 crew wounded |

| 21st Mar 1941 |

9K+BR |

6167 |

le Havre Crashed 4 crew kiled |

| 24th Mar 1941 |

9K+KT |

6154 |

Villacoublay Crashed 4 crew kiled |

Aircrew casualties

Killed: 4 officers and 47 NCOs and airmen

Missing: 3 officers and 16 NCOs and airmen

Taken Prisoner POW: 2 officers and 5 NCOs and airmen

Wounded

Severely: 3 officers and 5 NCOs and airmen

Slightly: 3 officers and 7 NCOs and airmen

Aircraft lost/damaged: 100% 21; 70-80% 4; 45-60% 3; 25-40% 5; 15-20% 5

Article Source: Kampfgeschwader Edelweiss The History of a German Bomber Unit 1939-45

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred