Messerschmitt Bf 110D Stkz VJ+OQ flown by Rudolf Hess Werk Nr 3869 crashed Scotland 10th May 1941

Photo: The remains of one particularly interesting enemy machine that came to Cowley, was the mount of Deputy Fuhrer Rudolf Hess, Bf 110 (3869) VJ+OO, which he flew to Scotland on 10 May 1941 ,and then baled-out in order to see and talk with Lord Douglas Hamilton, someone of note he had met in pre-war Germany. The wreckage had a rather bizarre ending in that it was not intended to be put on public display however, it was placed on show in St Giles, Oxford for a full day, much to the annoyance of the authorities. I understand that a fuselage side panel bearing the aircraft's letter coding VJ+OO is now with the IWM at Lambeth. For some years it was rumoured that the pilot's seat was stored privately in Scotland, but how true this is, is conjectural.

Source: http://www.air-britain.com/sampleaeromil.pdf

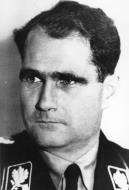

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (26 April 1894 - 17 August 1987)

Institute for Historical ReviewThe Inside Story of the Hess Flight

On May 10, 1941, Rudolf Hess made his daring flight from Germany to Britain in a vain bid to stop the tragic conflict between two nations he admired and loved. When Hitler's Deputy parachuted to earth from a Messerschmitt fighter over south Scotland, Germany and Britain had already been at war with each other for twenty months.

It is well known that Hess made this unprecedented move to impress on Britain's war leaders just how earnestly Germany desired peace. But even after the passage of forty years, much about the famous episode remains shrouded in mystery. The biggest question is whether Hitler knew in advance about the flight. Did he even order Hess on this mission of peace, as some insist? We cannot be sure if Hess would reveal the truth if he could. His ardent loyalty to Hitler might keep him from telling the whole story even if he were able. The truth may not be known until the secret British government documents on the matter are one day finally removed from the closed archives and made available to the world in uncensored form.

Still, there is strong evidence that Hess risked his life for peace under orders from Adolf Hitler himself. In its issue of May 1943, the American Mercury published 'The Inside Story of the Hess Flight,' a remarkable article which self-assuredly reported that the flight was personally directed by Hitler and completely expected by the British.

In 1943 the American Mercury was a popular, highly successful and very 'establishment' monthly. It was quite different from the iconoclastic journal that H. L. Mencken had founded and edited many years before.

Although the article on the Hess flight appeared anonymously, the magazine's editors vouched for its accuracy: 'The writer, a highly reputable observer, is known to us and we publish this article with full faith in its sources.' The Reader's Digest published a condensed version of the piece in its July 1943 issue and likewise declared it accurate: 'According to Allan A. Michie, The Reader's Digest's London correspondent, this account of the Hess flight corresponds to the version accepted by well-informed journalists in Britain.'

Written in the midst of war, the author's bellicose joy at the failure of the Hess peace venture may appear regrettable and even contemptible today. Still, the information it contains (if correct) puts both Germany and Britain in a very different light than the one originally intended by the author. Because of its unquestionable historical importance, this article deserves serious consideration today.

-- Mark Weber

Part I

Why Rudolf Hess took the sky road to Scotland has never been revealed officially, principally because two leaders of Allied strategy, Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, believed at the time that no useful purpose could be served by the telling. Hess was consigned to the limbo of hush-hush and all attempts to probe the craziest episode of the war were resolutely suppressed.

Today, two years after, many Englishmen and a few Americans know exactly why Hess came to England, and most of those in possession of the true story feel that it should now be told. For one thing, it would place before critics of Anglo-American policy towards Soviet Russia the vital and silencing fact that at a difficult moment, when he might have withdrawn his country from the war at Russia's expense, Churchill pledged Britain to continue fighting as a full ally of the newest victim of Nazi duplicity. There would have been some semblance of poetic justice to such a withdrawal-was it not Stalin who set the war in motion by signing a friendship pact with Hitler in 1939? But the British Prime Minister never even considered such action.

A few details are still unclear-only British Intelligence and several top-flight officials, know them; a few facts must still be kept dark for reasons of policy. But the essential story can be safely, and usefully, told. It makes one of the most fascinating tales of superintrigue in the annals of international relations. It adds up to a supreme British coup that must have shattered the pride of the Nazis in their diplomacy and their Secret Service. In that domain, it is fair to say, the Hess incident is a defeat equivalent to Stalingrad in the military domain.

Rudolf Hess did not 'escape' from Germany. He came as a winged messenger of peace, and no Parsifal in shining armor was ever more rigorously and loyally consecrated to his mission. He came not only with Adolf Hitler's blessing, but upon Hitler's explicit orders. Far from being a surprise, the arrival of Hess was expected by a limited number of Britishers, the outlines of his mission were known in advance, and the Nazi leader actually had an RAF escort in the final stage of his air journey.

On the basis of reliable information since obtained from German sources and from indications given by Hess himself, it is possible to reconstruct the situation in Berlin that led to the mad Hess undertaking.

By the beginning of 1941 Hitler, in disregard of the advice of some of his generals, had decided that he could no longer put off his 'holy war' against Russia. The attempt to knock out the Western democracies before turning to the East had failed. The alternative was an understanding with Great Britain which would leave Germany free to concentrate everything against Russia-a return, in some measure, to the basis of co-operation set up in Munich. Whatever Chamberlain and Daladier may have thought, the Germans had interpreted the Munich deal as a carte blanche for Nazi domination of Eastern Europe. The Allied guarantees to Poland and Rumania thereafter and their declaration of war, were indignantly denounced in Berlin as a democratic double-cross.

Hitler put out a tentative feeler in January 1941 in the form of an inquiry regarding the British attitude towards possible direct negotiations. It was not directed to the British Government but to a group of influential Britishers, among them the Duke of Hamilton, who belonged to the since discredited Anglo-German Fellowship Association. An internationally known diplomat served as courier. In the course of time a reply arrived in Berlin expressing limited interest and asking for more information. Tediously, cautiously, without either side quite revealing its hand, a plan was developed. When the German proposal of negotiations on neutral soil was rejected, Berlin countered with an offer to send a delegate to England. After all, had not Chamberlain flown to Germany?

A delegate was selected-Ernst Wilhelm Bohle, Gauleiter of all Germans abroad. Handsome, South African-born, Cambridge educated Willi Bohle was actually a British subject, though his passport was considerably out of date, and he seemed ideally suited for the mission. Several important foreign journalists in Berlin were let in on the secret that Bohle was being groomed for a very big and mysterious job abroad, and the story was planted in Turkish and South American papers to test British reaction. When weeks passed and the British press did not pick up the story, thus indicating an indifference to Bohle, Berlin became worried.

It was then that the Fuhrer came through with one of his 'geniale' ideas. Bohle was not the right man, he said. He did not have the national stature to impress the British. A really big Nazi would have to go, one whose name was inseparably linked with Hitler himself and whose presence could not possibly fail to command attention. He must be one, said Hitler, who would represent the 'goodness' of the German race, one whose sincerity was unquestionable. What is more, he must be able to speak officially for the German Government and to give binding commitments on the behalf of the Fuhrer. Providence, Hitler pointed out, had given Germany just the man-Walter Richard Rudolf Hess, Nazi Number Three, who in addition to fulfilling the other qualifications had grown up in the English quarter of Alexandria, spoke fluent English and 'understood the British mind.'

After Hitler transmitted his supreme and final offer-to send his own Deputy and closest friend directly to England-there was a long delay in replying. Possibly the imperturbable British required some time to recover from their astonishment. But finally Adolf's intuition was justified -- an acceptance of the proposal came through, details were arranged, and on May 10 Hess flew into the twilight.

Four months of intricate negotiations had preceded the flight. The Germans had pushed their proposal in the name of peace and Nordic friendship. Their British 'friends' were co-operative without being too eager or too optimistic -- there was no use overlooking the difficulties. As was only natural, progress was made slowly; there were ups and downs in the fortunes of the enterprise.

Part II

The one thing the Germans did not know was that they were negotiating with agents of the British Secret Service using the names -- and the handwriting -- of the Duke of Hamilton and other gentry of the Anglo-German Fellowship Association! The fact is that the initial communication, in January, brought personally by an eminent diplomat, never reached its destination, having been intercepted by the Secret Service. From then on the correspondence was handled entirely by astute British agents. Replies designed to whet the German appetite, replies encouraging the supposition that Britain was seeking a way out of its military difficulties, were sent to Berlin. The hook was carefully baited that caught the third largest fish in the Nazi lake.

It was perhaps his perverted love of Wagnerian contrast that led Hitler to choose the night of his Deputy's fateful flight for unloading five hundred tons of noisy death on London.

That night the subterranean plotting room of the RAF Fighter Command was static with !activity. The heaviest Nazi bomber force ever sent to Britain was pounding the capital, and new waves of planes were crossing the coast every fifteen minutes. When a report from an outlying radiolocation station on the Scottish coast announced the approach of an unidentified plane, the receiving operator at Fighter Command checked it off as 'one of ours' and promptly forgot it. On the tail of the first report came a second: the plane had failed to identify itself properly and its speed indicated that it was a fighter. Methodically, as one immune to surprises, the operator sent his flash to the plotting room and a hostile plane was pinpointed far up on the eastern coast of Scotland with an arrow to indicate that it was moving west.

By now inland stations were also picking up the mystery plane, obviously a fighter from its speed, although Scotland was far beyond the normal cruising range of any fighter. Consulted, the commanding officer at Fighter Command reacted in a manner that Fighter Command personnel still discuss with varying degrees of puzzlement. 'For God's sake,' he is reported to have shouted, 'Tell them not to shoot him down!' In a matter of seconds a fighter station in Scotland received a flash and two Hurricanes took off to trail the mystery plane with orders to force it down but under no conditions to shoot at it. While the small red arrows on the plotting table crept across Scotland, high officers at Fighter Command watched with absorbed interest. Near the tiny village of Paisley, almost on the west coast, they stopped. 'Made it,' the commanding officer is reported to have grunted. 'Thank God, he's down!'

In Lanarkshire, Scotland, David McLean, a farmer, watched a figure parachute into his field, and by the time the man had disentangled himself from the shrouds of his parachute, Farmer McLean was standing over him with a pitchfork. 'Are ye a Nazi enemy, or are ye one o' ours?' he asked. 'Not Nazi enemy; British friend,' the man replied with some difficulty because he had wrenched his ankle and was in extreme pain. Helped into the farmer's kitchen, he announced that his name was Alfred Horn and that he had come to see the Duke of Hamilton, laird of the great Dungavel estate ten miles away. The man talked freely, and to local Home Guardsmen Jack Paterson and Robert Gibson, who had arrived in the meantime, he admitted that he had come from Germany and was hunting the private aerodrome on Hamilton's estate when his fuel gave out and he had to bail out. 'My name is Alfred Horn,' he repeated frequently as though seeking recognition. 'Please tell the Duke of Hamilton I have arrived.'

With their instinctive distrust of aristocracy, the canny Scots became suspicious of the whole situation, and the parachutist was bundled off to the local Home Guard headquarters, where an excited, argumentative crowd soon gathered. Meanwhile, a kind of official reception committee composed of Military Intelligence officers and Secret Service agents was waiting at the private aerodrome on the Hamilton estate. The forced landing ten miles from the prearranged rendezvous was the only hitch in the plan. It was the hitch, presumably, which broke to the whole world sensational news which otherwise might have been kept on ice for a while if not for the duration.

When the 'reception committee' heard of the accident and finally found their visitor, he was being guarded by over a dozen defiant Home Guardsmen who were determined not to relinquish him. It took lengthy assurances that the man would remain safe in their custody, plus the arrival of Army reinforcements under instructions to co-operate with the 'committee,' to persuade the Guardsmen to give up their prisoner.

Still declaring that his name was Alfred Horn, Hess was placed in a military motorcar and driven to Maryhill Barracks near Glasgow. There he changed his story. 'I have come to save humanity,' he said. 'I am Rudolf Hess.' And he indicated that his visit was being expected by influential Englishmen -- a statement that was truer than he as yet suspected. His identity checked, Hess was taken to a military hospital to have his ankle treated, and with a Scots Guardsman on duty outside his door, spent his first night in the British Isles.

In the village of Paisley and many other parts of the Highlands, Scotsmen divided into factions-Scots nationalists and British loyalists, royalists and socialists-and throughout that night and for several days broke heads and knuckles over the issue of the German who came to Scotland. The loyalists and socialists suspected that either the Scots nationalists or royalists had been guilty of some treasonable skullduggery.

Hess passed a good night, and when his nurse brought breakfast on a tray the next morning at 8 a.m. he reminded her that on the continent one breakfasted later. She left the tray and departed, while he went back to sleep. When she returned at nine for the tray, the breakfast had not been touched, so she removed it, with the result that Hess spent his first morning in Britain without breakfast. Thereafter he breakfasted at eight.

Hitler's friend and deputy had come prepared for an indirect approach to the British Government through the Anglo-German Fellowship Association, to which a surprising number of prominent Britons adhered before the war. The actual approach, as planned by Winston Churchill, was exceedingly direct. Ivone Kirkpatrick, an astute super-spy in World War I and Councillor at the Berlin Embassy during the intervening years, flew to Scotland to receive the Hess plan for direct transmission to the British Government. Even Hitler could have asked no greater co-operation. Despite the absence of the Duke of Hamilton, Hess at this stage was still convinced that he was dealing with the Fellowship intermediaries.

It was to Kirkpatrick that the Nazi first poured out the details of Hitler's armistice and peace proposals. He was enthusiastic and voluble -- the stenographic report filled many notebooks. And he was most optimistic, since he was fully convinced that Britain was licked, knew it, and must therefore welcome the Fuhrer's generous offer of amity. His tone throughout was that of a munificent enemy offering a reprieve to a foe whose doom was otherwise sealed.

Part III

The terms of Hitler's peace proposal have been discussed up and down England not only in well-informed political circles but in pubs, bomb shelters and Pall Mall clubs. It was too elaborate a secret to be kept. Cabinet members presumably told their friends in Parliament and the MP's told their club colleagues and the news percolated down. The filter of time, plus such cross-checking as is possible on a subject that is officially taboo, enables the writer to give the general outline, withholding details.

Hitler offered total cessation of the war in the West. Germany would evacuate all of France except Alsace and Lorraine, which would remain German. It would evacuate Holland and Belgium, retaining Luxembourg. It would evacuate Norway and Denmark. In short, Hitler offered to withdraw from Western Europe, except for the two French provinces and Luxembourg [Luxembourg was never a French province, but an independent state of ethnically German origin], in return for which Great Britain would agree to assume an attitude of benevolent neutrality towards Germany as it unfolded its plans in Eastern Europe. In addition, the Fuhrer was ready to withdraw from Yugoslavia and Greece. German troops would be evacuated from the Mediterranean generally and Hitler would use his good offices to arrange a settlement of the Mediterranean conflict between Britain and Italy. No belligerent or neutral country would be entitled to demand reparations from any other country, he specified.

The proposal contained many other points, including plans for plebiscites and population exchanges where these might be necessitated by shifts in population that has resulted from the military action in Western Europe and the Balkans. But the versions circulating in authoritative circles all agree on the basic points outlined above.

In a prepared preamble, Hess explained the importance of Hitler's Eastern mission 'to save humanity,' and indicated how perfectly the whole arrangement would work out for Britain and France, not only from the ideological and security angles but also commercially. Germany, he pointed out, would take the full production of the Allied war industries until they could be converted to a peacetime basis, thus preventing economic depression. As Hess and his Fuhrer saw it, England and France would become, in effect, the arsenals of free capitalism against Asiatic communism. The actual slaying of the Bolshevik dragon Hitler reserved for Germany alone, so that by this act he could convince a doubting world of his benevolent intentions. Hess gave no information on the military plans for Eastern Europe and would not be drawn out on that point, since it was a problem for Germany alone.

For two days Hitler's emissary unfolded his proposals and Churchill's amanuensis made notes. Hess was certain his plan would be accepted; it is characteristic of German thinking that it never foresees the possibility of another point of view. He emphasized that his Leader would not quibble over details -- Britain could practically write its own peace terms. Hitler was only eager, as a humanitarian, to stop the 'senseless war' with a brother nation and thus incidentally guarantee supplies and safeguard his rear while fighting in the East.

With the prepared plan and the emissary's annotations in his notebooks, Kirkpatrick went to 10 Downing Street. The plan was communicated to Washington for an opinion, and the President, of course, confirmed the Prime Minister's decision. The answer would be a flat 'No,' but the two statesmen are reported to have agreed that open discussion of such a sensational offer would be undesirable at that time. They decided that the insanity explanation fed to the German people would also suffice for the rest of the world. Unlike the Germans and some Americans, no single Britisher believed a word of that story. Both London and Washington made repeated efforts to warn Russia of the coming German blows. The Russian leaders would not believe it-or pretended not to believe it-and certain Soviet diplomats insisted that the warnings were democratic 'tricks'. until the actual invasion took place.

Hess was not told of Churchill's decision and was permitted to assume that his proposals were under ardent discussion. At the hospital he rested easily and talked freely with his doctor, nurses and guards. He was tolerant and friendly until his doctor one morning made a typical British comment on Adolf Hitler, Hess thereupon staged a scene and remained surly and sulking for a week. When he was able to walk, he was flown to London, where he talked to Lord Beaverbrook, Alfred Duff Cooper and other government leaders. But Churchill refused his repeated requests for a meeting.

Only after he had talked himself out and could provide no further useful information, was Hess informed that his plan had been entirely rejected and that Britain was already Russia's ally. By that time he was aware, too, that the negotiations which preceded his flight had short-circuited the Fellowship crowd -- neither Hamiliton nor any of the others had known anything about the Hess visit until all of England knew it. Hess's shock and dismay resulted in a minor nervous breakdown, so that for a while the Nazi lie about his insanity came near being true. The news of the sinking of the Bismarck shook Hess so that he wept for an entire day.

Hess demanded that he be sent back to Germany, because, having come as an emissary, he was entitled to safe return. The British Government reasoned differently -- after all, he came as an emissary to private individuals, not to the Government directly -- and he became a special prisoner of war. He spends his existence in the manor house of a large English estate, with considerable freedom of movement on the well guarded grounds. His appetite is reported to be good. He spends most of his time reading German classics and perfecting his English. A book-dealer in London recently wrote to several of his customers who had purchased German books from him, inquiring whether they would care to resell them to another client: the client's name was given as Walter R. R. Hess.

This was not the first time England reduced a German stronghold by audacious Secret Service work. It was reported unofficially in Berlin that the Graf Spee was scuttled on orders sent over Admiral Raeder's signature by the cloak-and-dagger experts in the British Secret Service. Whether there is any truth to that or not, there is no doubt that when the whole story can be told the achievements of that Secret Service will astound the world. And the Hess episode is certain to stand out with a glory all its own among them.

Web References: http://www.ihr.org/jhr/v03/v03p291_Anon.html

WW2 HISTORY

Hess and Hamilon

The Truth,Historian and former wartime RAF navigator ROY NESBIT explains how newly-released files at The National Archives scotch the myth that the Duke of Hamilton was involved in secret peace negotiations with Germany

IN LATE 1985 THE then editor of Aeroplane Monthly, Richard Riding, asked me to examine the circumstances of the flight made by Rudol F Hess to Britain on May 10, 1941. The main objective was to discover the means by which Hess managed to achieve such a long flight, in a Messerschmitt Bf 110, from Augsburg in Southern Germany to his parachute descent at Floors Farm, to the west of Eaglesham in Renfrewshire.

He came down only 12 miles to the west of Dungavel House, the home of the Duke of Hamilton, with whom he wished to discuss the prospect of peace between Britain and Germany. It was a truly remarkable feat of pilot navigation. The results of my research were published in Aeroplane of November and December 1986. They concentrated on technical and navigational matters relating to the flight , but did not elaborate on Hess's political motives. However, they aroused much interest, and I was drawn into writing a book on the subject, in co-authorship with Belgian air historian Georges Van Acker, who is fluent in German and could gain access to relevant books, articles and papers in that language.

The outcome was The Flight of Rudolf Hess, with a foreword by the present Duke of Hamilton. It was published in hardback by Sutton Publishing in 1999 and then in paperback in 2002.

One topic discussed in thi s book was any association between the duke and Hess. It was ascertained that the two had never met, although both had attended several banquets during the Berlin Olympics of August 1936 and had sat at nearby tables. However, during that visit the duke (who at the time was the Marquis of Clydesdale) had been introduced by his brother David to Dr Albrecht Haushofer, a 33-year-old expert on the British constitution. He was the son of Maj-Gen Pro f Karl Haushofer, an exponent of German territorial expansion, and his part-Jewish wife, Martha.

Both father and son were on friendly terms with Hess and acted as advisors. In his subsequent friendship and meetings with Albrecht, the marqu is was keen to monitor the directions in which general thinking in Germany was moving. Of course, by the time Hess made his flight the political and military situation had been transformed. Serving in the Royal Auxiliary Air Force, Hamilton had commanded 602 (City of Glasgow) Sqn for a few years up to 1937. In the modified westland PV-3 he had made the first successful flight over Everest in 1933, and been awarded the Air Force Cross. He was not at his home in Dungavel when Hess arrived, but was on duty as a wing commander in command of RAF Turnhouse, a fighter station near Edinburgh.

The duke was the eldest of four brothers serving in the RAF. The next was Wg Cdr Lord George Nigel Douglas-Hamilton AFC, who was in RAF Intelligence. His duties had included a period as personal assistant to Lord Dowding. The third was Wg Cdr Lord Malcolm Douglas-Hamilton, who was working with the Air Staffin Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia, developing the Rhodesian Air Training Group.The youngest was Fg Off Lord David Douglas-Hamilton, a flying in structor. He later lost his life in 544 Sqn when his damaged Mosquito crashed on August 2, 1944, after struggling back from an operation near Dijon.

Georges and I had discovered from British and German records that Albrecht Haushofer had sent a letter to the duke on September 23, 1940, with Hess's knowledge, proposing a meeting in Lisbon to discuss relations between the two countries.

We also knew th at Hess believed he was interpreting the views of Hitler in hoping to negotiate peace. Of course, the Fuhrer wished to make a temporary truce with Britain. The great assault by the Luftwaffe on Britain had failed, and he had postponed hi s plans to invade the island by sea and air. He needed to concentrate his entire forces on the invasion of Russia, an event with cataclysmic consequences that began on June 22, 1941. Although he knew that peace feelers were being made through a neutral country, he was totally unaware of Hess's intended flight. No reply to Haushofers letter was ever received, and Hess decided that he should make the flight to meet the duke entirely on his ow n initiative.

The missing piece in our jigsaw was the content of Haushofer's letter and the circumstances following its arrival - but The National Archives (TNA, formerly the Public Record Office) has now been auth ori sed to release two large files entitled "Albrecht Haushofer", which fill this gap.

It transpires that the letter was forwarded via an address in Lisbon of a friend, Mrs Violet Roberts, the 70-year-old wife of a former Cambridge professor. She had spent some time in Portugal but lived in Cambridge. The letter was intercepted by the British Censor and passed to MI5, where it was handl ed by Col T.A. "Tar" Robertson.

These released files show clearly that neither the duke nor MI5 was involved in peace negotiations with Germany. Indeed, after clearing the duke, Robertson asked him to consider going to Lisbon to discuss matters with Haushofer. His purpose would not have been to negotiate peace, but to obtain intelligence about German policies.

The duke demurred at first, saying his brother David might be more capable of such a role, but he eventually agreed subject to certain conditions.

But the idea of organising the meeting came too late, and it was abandoned.

The files have been kept secret for a surprisingly long time, but they refute various conspiracy theories advanced on this subject. As regards the participants, Haushofer was murdered by the SS on April 23, 1945, and his parents committed suicide on March 11, 1946. Hess hanged himself in a military prison on August 17, 1987. The duke discussed his meeting with MI5 only with his immediate family, a few years before hi s death in 1973. However, he has now been completely vindicated by the content of these files. Their references are KV 2/ 1684 and KV 2/ 1685, and they are available for scrutiny by the public.

Rudolf Hess was born in 1894 and died in Spandau Prison in 19. Rudolf Hess was Hitler's deputy leader in the Nazi Party. Hess had been involved with the Nazi Party from its earliest days and was on the march to the Beer Hall that lead to his and Hitler's imprisonment at Landsberg Prison from 1923 to 1924. It was in prison that Hitler dictated "Mein Kampf" to Hess who acted as Hitler's personal secretary while in prison. In fact, Hess was seen by many to be Hitler's most loyal follower.

Painting Having switched off the engines and feathered the propellers of his Messerschmitt Bf ll0 and turned it almost on its back to avoid hitting the tail upon exit, Hess bales out over Scotland on May 10, 1941.

Painting by Charles J. Thompson GAvA.

Book References: Aeroplane Monthly April2005

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess

Rudolf Hess was born in 1894 and died in Spandau Prison in 19. Rudolf Hess was Hitler's deputy leader in the Nazi Party. Hess had been involved with the Nazi Party from its earliest days and was on the march to the Beer Hall that lead to his and Hitler's imprisonment at Landsberg Prison from 1923 to 1924.It was in prison that Hitler dictated "Mein Kampf" to Hess who acted as Hitler's personal secretary while in prison. In fact, Hess was seen by many to be Hitler's most loyal follower.

Hess had fought in World War One with a unit from Bavaria. He fought at the Battle of Ypres before he enrolled for the newly formed German Air Force. After the war, Hess joined Munich University and he met Hitler at a meeting of a society devoted to the study of Nordic myths and legends. In 1920, Hess became Hitler's political secretary.

To many in the party Hess remained an odd figure - distant and strange. To Hitler, he was simply a devoted follower who had shared with Hitler the ravages of the Battle of Ypres and imprisonment. With Hitler's support, the position of Hess in the party was unchallenged. In 1934, he was appointed deputy leader of the party and in 1939, he was appointed second in succession after G�ring to the position of Head of State.

To all people it appeared as if Hess was the perfect follower of Hitler. In his speeches, Hess proclaimed that:

"The party is Hitler and Hitler is Germany".

"Hitler is simply pure reason incarnate"Then in May 1941, Hess did something that took everybody by surprise. On May 10th, he took a Messerschmidt 110 and flew it solo to Scotland where he crash landed the plane. It seems that Hess took it upon himself to secure a negotiated peace between the British government (that, he stipulated, should not include Winston Churchill!) and Germany. Hess was found by a Scots farmer and arrested. Those who arrested Hess were impressed with his manners - he would not sit down until told that he could do so etc. Hess was interned, including a four day say at the Tower of London where he signed autographs for the warders - one of which is still in the warders bar. Hitler immediately stripped Hess of all the ranks he held in the Nazi Party including being a party member.

He was sent to trial at Nuremburg in 1946 where he was sent to prison for life. With other Nazi leaders, he was sent to Spandau Prison and from 1966 on, he was the only prisoner there. His death while in prison is a bit of a mystery. It appears that Hess committed suicide by hanging himself. However, there are those who believe that he was far too old and frail to do this by himself and that Hess may have received some assistance from others. Nothing has ever been proved. After the death of Hess, Spandau Prison was knocked down.

Web Referneces: http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/rudolf_hess.htm

Luftwaffe pilot Walter Nowotny 258 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Theodor Weissenberger 208 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Heinz Bar 175 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Franz Schall 133 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Rudolf Rademacher 126 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Adolf Galland 104 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Hermann Buchner 58 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Erich Hohagen 50 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Rudolf Sinner 39 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Ernst-Wilhelm Modrow 32 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Richard Altner 25 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Gunther Wegmann 21 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Wolfgang Schenck 18 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Franz Holzinger 10 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Helmut Lennartz 10 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Alfred 'Bubi' Schreiber 9 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Eduard Schallmoser 3 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Wilhelm Batel 1 kills

Luftwaffe pilot Joachim Fingerlos 1 kills

Bibliography: +

- Campbell, Jerry L. Messerschmitt BF 110 Zerstörer in Action. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, Inc., 1977. ISBN 0-89747-029-X.

- Caldwell, Donald and Richard Muller. The Luftwaffe over Germany: Defence of the Reich. London: Greenhill Books, 2007. ISBN 978-1-85367-712-0.

- Ciampaglia, Giuseppe. 'Destroyers in Second World War'. Rome: IBN editore, 1996. ISBN 88-86815-47-6.

- Deighton, Len. Fighter: The True Story of the Battle of Britain. London: Pimlico, 1996. ISBN 0-7126-7423-3.

- de Zeng, H. L., D. G. Stanket and E. J. Creek. Bomber Units of the Luftwaffe 1933-1945: A Reference Source, Volume 2. London: Ian Allan Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-1-903223-87-1.

- Donald, David, ed. Warplanes of the Luftwaffe. London: Aerospace, 1994. ISBN 1-874023-56-5.

- Geust, Carl-Fredrik and Gennadiy Petrov. Red Stars Vol 2: German Aircraft in the Soviet Union. Tampere, Finland: Apali Oy, 1998. ISBN 952-5026-06-X.

- Hirsch, R.S. and Uwe Feist. Messerschmitt Bf 110 (Aero Series 16). Fallbrook, California: Aero Publishers, Inc., 1967.

- Hooton, E.R.Luftwaffe at War; Blitzkrieg in the West: Volume 2. London: Chervron/Ian Allan, 2007. ISBN 978-1-85780-272-6.

- Hooton, E.R. Luftwaffe at War; Gathering Storm 1933-39: Volume 1. London: Chervron/Ian Allan, 2007. ISBN 978-1-903223-71-0.

- Ledwoch, Janusz. Messerschmitt Bf 110 (Aircraft Monograph 3). Gdańsk, Poland: AJ-Press, 1994. ISBN 83-86208-12-0.

- Likso, T. and D. Canak. Hrvatsko Ratno Zrakoplovstvo u Drugome Svjetskom Ratu (The Croatian Airforce in the Second World War). Zagreb, 1998. ISBN 953-97698-0-9.

- Mankau, Heinz and Peter Petrick. Messerschmitt BF 110/Me 210/Me 410: An Illustrated History. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0-7643-1784-9.

- Murray, Willamson. Strategy for Defeat: The Luftwaffe 1935-1945. Maxwell AFB, Al: Air Power Research Institute, 1983. ISBN 0-16-002160-X.

- Mackay, Ron. Messerschmitt Bf 110. Wiltshire, UK: The Crowood Press, 2000. ISBN 1-86126-313-9

- Middlebrook, Martin. The Peenemunde Raid: The Night of 17-18 August 1943. Barnsely, UK: Pen & Sword Aviation, 2004. ISBN 1-84415-336-3.

- Munson, Kenneth. Fighters and Bombers. New York: Peerage Books, 1983. ISBN 0-907408-37-0.

- Price, Alfred. Messerschmitt Bf 110 Night Fighters (Aircraft in Profile No. 207). Windsor, Berkshire, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1971.

- Savic, Dragan and Boris Ciglic. Croatian Aces of World War II (Osprey Aircraft of the Aces - 49). London: Oxford, 2002. ISBN 978-1-84176-435-1.

- Treadwell, Terry C. Messerschmitt Bf 110(Classic WWII Aviation). Bristol, Avon, UK: Cerberus Publishing Ltd., 2005. ISBN 1-84145-107-X.

- Van Ishoven, Armand. Messerschmitt Bf 110 at War. Shepperton, Surrey: Ian Allan Ltd., 1985. ISBN 0-7110-1504-X.

- The Messerschmitt Bf 110 in Color Profile 1939-1945 John Vasco and Fernando Estanislau by Schieffer Publications. ISBN:0-7643-2254-0

- Wagner, Ray and Heinz J. Nowarra. German Combat Planes: A Comprehensive Survey and History of the Development of German Military Aircraft from 1914 to 1945. New York: Doubleday, 1971.

- Weal, John. Messerschmitt Bf 110 Zerstörer Aces World War Two. London: Osprey, 1999. ISBN 1-85532-753-8.

Magazine References: +

- Airfix Magazines (English) - http://www.airfix.com/

- Avions (French) - http://www.aerostories.org/~aerobiblio/rubrique10.html

- FlyPast (English) - http://www.flypast.com/

- Flugzeug Publikations GmbH (German) - http://vdmedien.com/flugzeug-publikations-gmbh-hersteller_verlag-vdm-heinz-nickel-33.html

- Flugzeug Classic (German) - http://www.flugzeugclassic.de/

- Klassiker (German) - http://shop.flugrevue.de/abo/klassiker-der-luftfahrt

- Le Fana de L'Aviation (French) - http://boutique.editions-lariviere.fr/site/abonnement-le-fana-de-l-aviation-626-4-6.html

- Le Fana de L'Aviation (French) - http://www.pdfmagazines.org/tags/Le+Fana+De+L+Aviation/

- Osprey (English) - http://www.ospreypublishing.com/

- Revi Magazines (Czech) - http://www.revi.cz/

Web References: +

- Wikipedia.org - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Messerschmitt

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

If you love our website please subscribe to our YouTube video channel

Please donate so we can make this site even better !!