Invasion of Yugoslavia

OPERATION No. 25

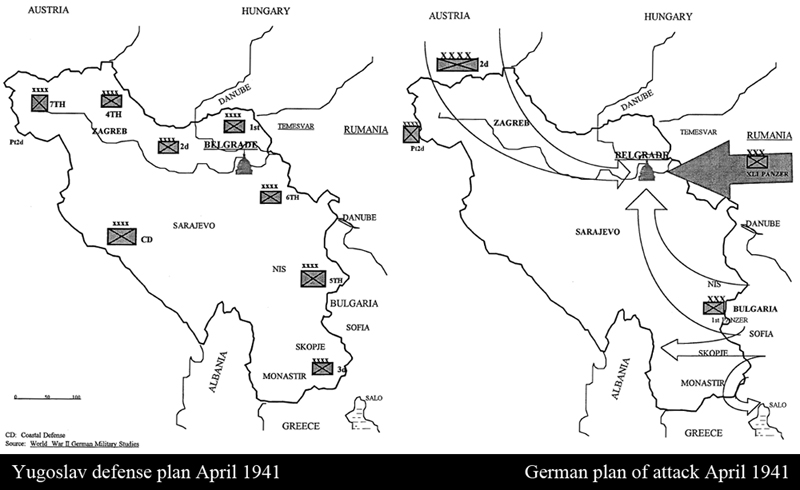

The operation in Yugoslavia took its code name from the directive number that Hitler issued to the German High Command for the invasion of Yugoslavia. It directed a joint ground and air offensive along two axis of advance converging on the capitol, Belgrade. This was later revised by the German High Command, to three axis of advance.(See Appendix B) Coalition support would be obtained from its allies by promising land acquisitions to Italy, Hungary and Bulgaria.[D1]

The overall command would be by General Maximilian von Weichs of the Second Army, then designated the Second Army Group with the addition of the First Panzer Group from the Twelfth Army and the independent XLI Panzer Corps. (See Appendix D for German Order of Battle)[D2]

The operational scheme was a combined arms, multi-axis attack aimed at the operational centers of gravity and coordinated with other operations in the area. The Second Army would attack south from Graz, Austria along the Drava and Sava rivers. The First Panzer Corps would attack north from the vicinity of Sofia by way of Nis. The XLI Panzer Corps would attack west from the vicinity of Timisoara in Rumania. All forces converging on Belgrade.

The intent was to crush the Yugoslav Army quickly, to prevent them from just melting away into the mountains to conduct extensive guerrilla operations later. The Luftwaffe would support the ground offensive and destroy all Yugoslav Air Forces and attack the command and control facilities located in Belgrade. In conjunction with the attacks on Yugoslavia, the Twelfth Army Group would initiate its attack on Greece from southwestern Bulgaria as previously planned.[D3]

A key to the success of this operation was the ability to secure the numerous river crossings that the attacking forces would need and to maintain the Danube River open for resupply. To this end the Germans executed limited objective attacks to secure the river crossings in the Second Army's zone while employing engineers along the Danube to preclude sabotage.

Extract from Hitler's War Directive No 25:

Plan of Attack on Yugoslavia

March 27, 1941

Chronological table of Events leading to the fall of Yugoslavia

Date time Source: World War II Military Studies

- 27 Sep. 1940 Germany, Italy, and Japan sign the Tripartite Pact.

- 7 Oct. 1940 German troops enter Rumania.

- 12 Oct. 1940 Hitler postpones invasion of Great Britain until spring 1941.

- 28 Oct. 1940 Italy invades Greece from Albania.

- 4 Nov. 1940 Hitler orders preparations for eventual intervention in Greece.

- 4 Nov. 1940 Royal Air Force begins to operate from Greek airfields.

- 20 Nov. 1940 Hungary adheres to Tripartite Pact.

- 23 Nov. 1940 Rumania joins Tripartite Pact.

- 28 Nov. 1940 Hitler confers with Yugoslav Foreign Minister Cincar-Marcovic and asks Yugoslavia to join Tripartite Pact.

- 5 Dec. 1940 Hitler conference, Army plans for campaigns against Greece and Russia presented.

- 13 Dec. 1940 Directive No. 20 is issued, outlining Operation MARITA, the campaign against Greece.

- 18 Dec. 1940 Directive No. 21 issued, ordering preparations for Operation BARBAROSSA, the campaign against Russia.

- 14 Feb. 1941 Hitler urges YUGOSLAV Premier Cvetkovic to join Tripartite Pact.

- 17 Feb. 1941 Bulgaria and Turkey conclude treaty of friendship.

- 28 Feb. 1941 German troops bridge the Danube.

- 1st March 1941 Bulgaria joins Tripartite Pact.

- 2th March 1941 German troops enter Bulgaria.

- 4th March 1941 Hitler confides with Prince Regent Paul of Yugoslavia.

- 7th March 1941 British Expeditionary Force begins to land in Greece.

- 9-16th March 1941 Italian spring offensive in Albania.

- 18th March 1941 Yugoslav privy council decides to join Tripartite Pact.

- 25th March 1941 Yugoslavia signs Tripartite Pact.

- 26-27th March 1941 Yugoslavia coup d'etat.

- 27th March 1941 Directive No. 25 is issued, outlining Operation 25, the campaign against Yugoslavia.

- 29th March 1941 Conference of German Army commanders responsible for campaign in Balkans.

- 6th April 1941 German air bombardment of Belgrade Twelfth Army invades southern Yugoslavia and Greece. Second Army launches limited-objective attacks against Yugoslavia.

- 7th April 1941 Operation BARBAROSSA postponed to 22 June. German troops enter Skoplje.

- 8th April 1941 First Panzer Group starts drive toward Belgrade.

- 9-10th April 1941 XLVI Panzer Corps enters the race for Belgrade.

- 10th April 1941 Start of Second Army drive on Zagreb and capture of the city. Croatia proclaims itself an independent state. XLIX Mountain and LI Infantry Corps cross northwestern Yugoslav border. First Panzer Group reaches point forty miles from Yugoslav capital.

- 11th April 1941 XLI Panzer Corps advances to within forty-five miles of Belgrade. German mountain troops cross the Vardar.

- 12th April 1941 Fall of Belgrade

- 14th April 1941 Beginning of Yugoslav armistice negotiations.

- 15th April 1941 German troops enter Sarajevo.

- 17th April 1941 Yugoslav representatives sign unconditional surrender.

- 18th April 1941 German armistice with Yugoslavia becomes effective at 1200.

1941

It only took 11 days for the fall of Yugoslavia following Hitlers Orders.

- 5:12 am on 6 April 1941, German, Italian and Hungarian forces attacked Yugoslavia

- On 17 April, representatives of Yugoslavia's various regions signed an armistice with Germany in Belgrade, ending 11 days of resistance against the invading German Army (Wehrmacht Heer).

Belligerents:

Axis:

Germany, Italy and Hungary

Commanders and Leaders:

Maximilian von Weichs

Wilhelm List

Vittorio Ambrosio

Elemér Gorondy-NovákStrength:

700,000

Casualties and losses:

Germany: (Official German WW2 figures) 151 killed 392 wounded 15 missing 60+ aircraft shot down and over 70 aircrew killed or missing.

Italy: 3,324 killed or wounded 10+ aircraft shot down, 22 damaged.

Hungary: 120 killed 223 wounded 13 missing 1+ aircraft shot down.

Belligerents:

Allies:

Yugoslavia

Commanders and Leaders:

Dušan Simović

Milorad Petrović

Milutin Nedić

Milan Nedić

Petar Nedeljković

Vladimir Čukavac

Dimitrije Živković

Dušan TrifunovićStrength:

Casualties and losses:

Thousands of civilians and soldiers killed 254,000-345,000 captured by Germans, 30,000 by Italians (Official German record: Of this 6298 officers and 337,864 soldiers) 49 aircraft shot down, 103 pilots and aircrew killed 211 aircraft captured 3 destroyers and 3 submarines captured.

German Order of Battle for the Invasion of Yugoslavia

Second Army - General Maximilian von Weichs

- XLIX Mountain Corps - Gen. Ludwig Kuebler

1st Mountain Div.

538th Frontier Guards Div.- LI Infantry Corps - Gen. Hans Reinhardt

101st Light Infantry Div.

132d Infantry Div.

183d Infantry Div.- LII Infantry Corps (High Command Reserve) - Gen. Kurt von Briesen

79th Infantry Div.

125th Infantry Div.- XLVI Panzer Corps - Gen. Heinrich von Vietinghoff

8th Panzer Div.

14th Panzer Div.

16th Motorized Infantry Div.FIRST Panzer Group - Gen. Ewald von Kliest

- XIV Panzer Corps - Gen. Gustav von Wietersheim

5th Panzer Div.

11th Panzer Div.

29th Infantry Div.

4th Mountain Div.- XI Infantry Corps Gen. Joachim von Kotzfleisch

60th Motorized Infantry Div.XLI Panzer Corps - Gen. Georg-Hans Reinhardt

- 2d SS Motorized Infantry Div.

Motorized Inf Regiment(Rein), 'Gross Deutschland'

Panzer Regiment, 'Hermann Goering'Invasion of Yugoslavia

The Invasion of Yugoslavia (code-name Directive 25 or Operation 25), also known as the April War (Croatian: Travanjski rat, Serbian/Bosnian: Aprilski rat, Slovene/Macedonian: Aprilska vojna) or the Balkan campaign (German: Balkanfeldzug), was the Axis Powers' attack on the Kingdom of Yugoslavia which began on 6 April 1941 during World War II. The invasion ended with the unconditional surrender of the Royal Yugoslav Army on 17 April 1941, annexation and occupation of the region by the Axis powers and the creation of the Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, or NDH).

The Invasion of Yugoslavia began at 5:12 am on 6 April 1941, German, Italian and Hungarian forces attacked Yugoslavia. The German Air Force (Luftwaffe) bombed Belgrade and other major Yugoslav cities. On 17 April, representatives of Yugoslavia's various regions signed an armistice with Germany in Belgrade, ending 11 days of resistance against the invading German Army (Wehrmacht Heer). More than 300,000 Yugoslav officers and soldiers were taken prisoner.

The Axis Powers occupied Yugoslavia and split it up. The Independent State of Croatia was established as a Nazi satellite state, ruled by the fascist militia known as the Ustaše that came into existence in 1929, but was relatively limited in its activities until 1941. German troops occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as part of Serbia and Slovenia, while other parts of the country were occupied by Bulgaria, Hungary, and Italy. From 1941-45, the Croatian Ustaše regime murdered around 500,000 people, 250,000 were expelled, and another 200,000 were forced to convert to Catholicism; the victims were predominantly Serbs but included 37,000 Jews.[52]

The Background

In October 1940, Fascist Italy had attacked Greece only to be forced back into Albania. German dictator Adolf Hitler recognised the need to go to the aid of his ally, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. Hitler did this not only to restore diminished Axis prestige, but also to prevent the United Kingdom from being able to bomb the Romanian oilfields from which Germany obtained most of her oil.[1]

Following agreements with Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria that they would join the Axis, Hitler put pressure on Yugoslavia to join the Tripartite Pact. The Regent, Prince Paul of Yugoslavia, succumbed to this pressure on 25 March 1941. However, this move was deeply unpopular amongst the anti-Axis Serbian public and military. A coup d'état was launched on 27 March 1941 by anti-Paul Serbian military officers, and the Regent was replaced on the throne by King Peter II of Yugoslavia.[4]

Upon hearing news of the coup in Yugoslavia, Hitler called his military advisers to Berlin on 27 March. Hitler took the coup as a personal insult, and was so angered that he was determined 'without waiting for possible declarations of loyalty of the new government to destroy Yugoslavia militarily and as a nation.'[5]

The Royal Yugoslav Armed Forces

Equipment and organization

Yugoslav designed and built Rogozarski IK-3 fighter aircraft, in camouflage colors at the end of 1940. This particular aircraft was flown by Eduard Banfić on 6 and 7 April 1941 in the air battle for the defense of Belgrade. Banfić was credited with shooting down 2 confirmed and one probable German aircraft during this period.

Formed after World War I, the Royal Yugoslav Army was still largely equipped with weapons and material from that era, although some modernization with Czech equipment and vehicles had begun. Of about 4,000 artillery pieces, many were aged and horse-drawn, but about 1,700 were relatively modern, including 812 Czech 37mm and 47mm anti-tank guns. There were also about 2,300 mortars, including 1600 modern 81mm pieces, as well as twenty four 220 and 305mm pieces. Of 940 anti-aircraft guns, 360 were 15 and 20mm Czech and Italian models. All of these arms were imported, from different sources, which meant that the various models often lacked proper repair and maintenance facilities.[6]

The only mechanized units were six motorized infantry battalions in the three cavalry divisions, six motorized artillery regiments, two tank battalions equipped with one-hundred-and-ten tanks, one of which had Renault FT-17s models of First World War origin and the other fifty-four modern French Renault R35 tanks, plus an independent tank company with eight Czech SI-D tank destroyers. Some one-thousand trucks for military purposes had been imported from the United States of America in the months just preceding the invasion.[7]

Fully mobilized, the Royal Yugoslav Army could have put 28 infantry divisions, 3 cavalry divisions, and 35 independent regiments in the field. An independent parachute unit, of company size, was formed in late 1939, but was not yet combat-ready.[8]

Of the independent regiments, 16 were in frontier fortifications and 19 were organized as combined regiments, or 'Odred', around the size of a reinforced brigade. Each Odred had one to three infantry regiments and one to three artillery battalions, with three organised as 'alpine' units. The German attack, however, caught the army still mobilizing, and only some 11 divisions were in their planned defense positions at the start of the invasion. The units were filled to between 70 and 90 percent of their strength as mobilization was not completed. The strength of the Royal Yugoslav Army was about 1,200,000 as the German invasion got underway.[2]

The Royal Yugoslav Air Force had over 450 front-line aircraft of domestic (notably the IK-3), German, Italian, French, and British origin, of which more than half were modern types. Organized into twenty-two bomber squadrons and nineteen fighter squadrons, the main aircraft types in operational use included seventy-three Messerschmitt Bf 109 E, thirty-eight Hawker Hurricane I (with more being built under licence in Yugoslavia), thirty Hawker Fury II, eight Ikarus IK-2, and six Rogozarski IK3 fighters (plus more under construction), sixty-three Dornier Do 17 K (including 40 plus licence built), sixty Bristol Blenheim I (including some 40 licence built) and forty Savoia Marchetti SM-79 K bombers. The Naval Aviation units comprised 8 squadrons equipped with, amongst other auxiliary types, twelve Dornier Do 22 K and fifteen Rogozarski SIM-XIV-H locally designed and built maritime patrol float-planes.

The aircraft of the Yugoslav airline Aeroput, consisting mainly of six Lockheed Model 10 Electras, three Spartan Cruisers, and one de Havilland Dragon were mobilised to provide transport services to the Air Force.[9]

The Royal Yugoslav Navy was equipped with one elderly ex-German light cruiser (suitable only for training purposes), 1 large modern destroyer flotilla leader of British design, 3 modern destroyers of French design (2 built in Yugoslavia plus another still under construction), 1 seaplane tender, 4 modern submarines (2 older French-built and 2 British-built) and 10 modern motor torpedo boats (MTBs), of the older vessels, there were 6 ex-Austrian Navy medium torpedo boats, 6 mine-layers, 4 large armoured river monitors and various auxiliary craft.[10]

Deployment

The Yugoslav Army had purchased 54 R35 Tanks from France in the late 1930s, seen here taking part in manoeuvres in 1940.

The Royal Yugoslav Army was organized into three army groups and the coastal defense troops. The 3rd Army Group was the strongest with the 3rd, 3rd Territorial, 5th and 6th Armies defending the borders with Romania, Bulgaria and Albania. The 2nd Army Group with the 1st and 2nd Armies, defended the region between the Iron Gates and the Drava River. The 1st Army Group with the 4th and 7th Armies, composed mainly of Croatian troops, was in Croatia and Slovenia defending the Italian, German (Austrian) and Hungarian frontiers.[7][11]

The strength of each 'Army' amounted to little more than a corps, with the 3 Army Groups consisting of the units deployed as follows; The 3rd Army Group's 3rd Army consisted of 4 infantry divisions and one cavalry odred; the 3rd Territorial Army with 3 infantry divisions and one independent motorized artillery regiment; the 5th Army with 4 infantry divisions, 1 cavalry division, 2 odred and one independent motorized artillery regiment and the 6th Army with 3 infantry divisions, the 2 Royal Guards brigades (odred) and 3 infantry odred. The 2nd Army Group's 1st Army had 1 infantry and 1 cavalry divisions, 3 odred and 6 frontier defence regiments; the 2nd Army had 3 infantry divisions and 1 frontier defence regiment. Finally, the 1st Army Group consisted of the 4th Army, with 3 infantry divisions and one odred, whilst the 7th Army had 2 infantry divisions, 1 cavalry division, 3 mountain odred, 2 infantry odred and 9 frontier defence regiments. The Strategic, 'Supreme Command' Reserve in Bosnia comprised 4 infantry divisions, 4 independent infantry regiments, 1 tank battalion, 2 motorized engineer battalions, 2 motorized heavy artillery regiments, 15 independent artillery battalions and 2 independent anti-aircraft artillery battalions. The Coastal Defence Force, on the Adriatic opposite Zadar comprised 1 infantry division and 2 odred, in addition to fortress brigades and anti-aircraft units at Šibenik and Kotor.[12]

On the eve of invasion, clothing and footwear were available for only two-thirds or so of the potential front-line troops and only partially for other troops; some other essential supplies were available for only a third of the front-line troops; medical and sanitary supplies were available for only a few weeks, and supplies of food for men and feed for livestock were available for only about two months. In all cases there was little or no possibility of replenishment.[13]

Beyond the problems of inadequate equipment and incomplete mobilization, the Royal Yugoslav Army suffered badly from the Serbo-Croat schism in Yugoslav politics. 'Yugoslav' resistance to the invasion collapsed overnight. The main reason was that none of the subordinate national groups; Slovenes, Croats were prepared to fight in defence of a Serbian Yugoslavia. Also, so that the Slovenes did not feel abandoned, defences were built on Yugoslavia's northern border when the natural line of defence was much further south, based on the rivers Sava and Drina. The only effective opposition to the invasion was from wholly Serbian units within the borders of Serbia itself.[14]

The Germans, thrusting north-west from Skoplje, were held up at Kacanik Pass and lost several tanks (P39, Buckley C 'Greece and Crete 1941' HMSO 1977). In its worst expression, Yugoslavia's defenses were badly compromised on April 10, 1941, when some of the units in the Croatian-manned 4th and 7th Armies mutinied, and a newly formed Croatian government hailed the entry of the Germans into Zagreb the same day.[15] The Serbian General Staff were united on the question of Yugoslavia as a 'Greater Serbia', ruled, in one way or another, by Serbia. On the eve of the invasion, there were 165 generals on the Yugoslav active list. Of these, all but four were Serbs.[16]

Operations

Starting on 6 April 1941, Axis armies invaded from all sides and the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) bombed Belgrade. German armies were the first to cross the border with Hungarian and Italian armies following a few days later. Tsar Boris III avoided committing Bulgarian troops to the invasion by claiming that all of his battle worthy troops were guarding the flank of Germany's 12th Army against Turkey.[17]

In a similar manner, while Romania was a staging area for German forces, no Romanian troops were committed to the invasion.

Bombing of Belgrade

Luftflotte 4 of the German Air Force (Luftwaffe), with a strength of seven Combat Formations (Kampfgruppen) had been committed to the campaign in the Balkans.[18] Hitler, infuriated at Yugoslavia's defiance, ordered the implementation of Operation Punishment (Unternehmen Strafgericht). At 7 am on 6 April the Luftwaffe opened the assault on Yugoslavia by conducting a saturation-type bombing raid on the capital. Flying in relays from airfields in Austria and Romania, 300 aircraft, of which a quarter were Junkers Ju 87 Stukas, protected by a heavy fighter escort began the attack.[19] The dive-bombers were to silence the Yugoslav anti-aircraft defences while the medium bombers consisting mainly Dornier Do 17 and Junkers Ju 88 attacked the city. The initial raid was carried out at fifteen-minute intervals in three distinct waves, each lasting for approximately twenty minutes. Thus, the city was subjected to a rain of bombs for almost one and a half hours. The German bombers directed their main effort against the center of the city, where the principal government buildings were located. The medium bomber Kampfgruppen continued their attack on the city for several days while the Stuka dive bomber wings (Stukageschwaders) were soon diverted to Yugoslav airfields.

When the attack was over, some 4,000 inhabitants lay dead under the debris. This blow virtually destroyed all means of communication between the Yugoslav high command and the forces in the field, although most of the elements of the general staff managed to escape to one of the suburbs.

Having thus delivered the knockout blow to the enemy nerve center, the Luftwaffe was able to devote its maximum effort to military targets such as Yugoslav airfields, routes of communication, and troop concentrations, and to the close support of German ground operations.

The Yugoslav Air Force put up its Belgrade defence interceptors from the six squadrons of the 32nd and 51st Fighter Groups to attack each wave of bombers, although as the day wore on the four squadrons from the 31st and 52nd Fighter Groups, based in central Serbia, also took part. The Messerschmitt 109E, Hawker Hurricane Is and Rogozarski IK-3 fighters scored at least twenty 'kills' amongst the attacking bombers and their escorting fighters on 6 April and a further dozen shot down on 7 April. The desperate defence by the Yugoslav Air Force over Belgrade cost it some 20 fighters shot down and 15 damaged.[20]

https://www.asisbiz.com/il2/Hurricane/RYAF.htmlAir Battle

The Ikarus IK-2 was a Yugoslav-designed and built fighter aircraft which entered service in the late 1930s. One squadron of 8 aircraft was based in Bosnia at the time of the invasion, mixing it with Luftwaffe Messerschmitt Bf 109s. Four captured examples were subsequently used by the Air Force of the Independent State of Croatia.

JKRV Hawker Hurricane. Some 24 British built and 20 Yugoslav built Hurricanes served in the JKRV, with pilots claiming several victories over German and Italian aircraft. Six captured examples were forwarded to the Romanian Air Force by Germany after the capitulation of Yugoslavia.

Following the Belgrade Coup on 25 March 1941, the Yugoslav armed forces were put on alert, although the army was not fully mobilised for fear of provoking Hitler. The Royal Yugoslav Air Force (JKRV) command decided to disperse its forces away from their main bases to a system of 50 auxiliary airfields that had previously been prepared. However many of these airfields lacked facilities and had inadequate drainage which prevented the continued operation of all but the very lightest aircraft in the adverse weather conditions encountered in April 1941.[21] Despite having superior aircraft to some of the previously German-occupied eastern European nations such as Poland or Czechoslovakia, the JKRV could simply not match the overwhelming Luftwaffe and Regia Aeronautica superiority in terms of numbers, tactical deployment and combat experience. As a result, the 11 day fight put up by the JKRV was nothing short of extraordinary.

The bomber and maritime force hit targets in Italy, Germany (Austria), Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania and Greece, as well as attacking German, Italian and Hungarian troops. Meanwhile the fighter squadrons inflicted not insignificant losses on escorted Luftwaffe bomber raids on Belgrade and Serbia, as well as upon Regia Aeronautica raids on Dalmatia, Bosnia, Herzegovina and Montenegro. The JKRV also provided direct air support to the hard pressed Yugoslav Army by strafing attacking troop and mechanized columns in Croatia, Bosnia and Serbia (sometimes taking off and strafing the troops attacking the very base being evacuated).[22]

Little wonder then that after a combination of air combat losses, losses on the ground to enemy air attack on bases and the overrunning of airfields by enemy troops, that after 11 days the JKRV almost ceased to exist. It must, however, be noted that between 6 and 17 April 1941 the JKRV received an additional 8 Hawker Hurricane Is, 6 Dornier Do-17Ks, 4 Bristol Blenheim Is, 2 Ikarus IK 2s, 1 Rogozarski IK-3 and 1 Messerschmitt Bf 109 from the local aeronautical industry's aircraft factories and work-shops.[23]

The JKRV's Dornier bomber force provides an illustrative case in point. At the beginning of the April war, the Royal Yugoslav Air Force was armed with some 60 German designed Dornier Do 17Ks, purchased by Yugoslavia in the autumn of 1938, together with a manufacturing licence. The sole operator was 3 vazduhoplovni puk (3rd bomber regiment) composed of two bomber groups; the 63rd Bomber Group stationed at Petrovec airfield near Skopje and the 64th Bomber Group stationed at Milesevo airfield near Priština. Other auxiliary airfields had also been prepared to aid in dispersal.[22]

During the course of hostilities, the State Aircraft Factory in Kraljevo managed to produce six more aircraft of this type. Of the final three, two were delivered to the JKRV on 10 April and one was delivered on 12 April 1941.

On 6 April, Luftwaffe dive-bombers and ground-attack fighters destroyed 26 of the Yugoslav Dorniers in the initial assault on their airfields, but the remaining aircraft were able to effectively hit back with numerous multi-ship attacks on German mechanized columns and upon Bulgarian airfields.[24]

By the end of the campaign total Yugoslav losses stood at four destroyed in aerial combat and 45 destroyed on the ground.[25] Between 14th and 15 April, the seven remaining Do 17K flew to Nikšić airfield in Montenegro and took part in the evacuation of King Petar II and members of the Yugoslav government to Greece. During this operation, Yugoslav gold reserves were also airlifted to Greece by the seven Do 17s,[25] as well as by Savoia Marchetti SM-79Ks and Aeroput Lockheed Model 10 Electras but after completing their mission, five Do 17K were destroyed on the ground when Italian aircraft attacked the Greek-held Paramitia airfield. Only two Do 17Ks escaped destruction in Greece and later joined the British Royal Air Force (RAF) in the Kingdom of Egypt.

At 16:00 on the 15 April the C-in-C of Luftflotte 4, Generaloberst Alexander Löhr received orders from Hermann Göring to wind down the air-offensive and transfer the bulk of the dive-bomber force to support the campaign in Greece.[26]

A total of 18 bomber, transport and maritime patrol aircraft (2 Dornier Do 17K, 4 Savoia Marchetti SM-79K, 3 Aeroput Lockheed Model 10 Electra, 8 Dornier Do-22K and 1 Rogozarski SIM-XIV-H) succeeded in escaping to the Allied base in Egypt at the end of the campaign.[9]

Dogfights over Belgrade - The First Day.

Written by Saso Knez

Furious because a small nation resisted the almighty German war machine Hitler ordered the attack on Yugoslavia. In Hitler's 'Order 25' the role for Luftwaffe was clear: the destruction of JKRV (Jugoslovensko Kraljevsko Ratno Vazduhoplovstvo - Yugoslovian Royal Air Force) and the bombardment of Belgrade.

For Operation 'MARITA', against Yugoslavia and Greece, the Luftwaffe dropped 1090 aircrafts (Luftflotte 4) and Germans were supported also by additinal 660 Italian and some Hungarian planes. JKRV was able to resist by totally 470 first line aircrafts, but only 269 planes were airworthy modern types. In first day of attack Luftwaffe concentrated mostly on Yugoslavian airbases, destroying a part of JKRV force before take off. But soon Yugoslavian pilots appeared in air...

The German attack came at the wrong time for the 102 eskadilju, 32 vazduhoplovne grupe as witnessed by its CO Mihajlo Nikolic:

".....In Mostar we were supposed to be relived by the Fighter Scholl from Nis. While waiting for them our planes were turning ready for their 100hrs check, because they all had from 110-130hrs flying time. The Me 109E had the Daimler Benz 601 engine, and the only repair shop for these engines was in Zemun. So on Saturday 5. April in the evening we landed on the Zemun airfield. The airplane of August Kovac engine failed while still on the runway, and the others were practically unflyable. But we were immediately included in the 51. vazduhoplovna grupa, which flew IK-3, but only had six of them-three each squadron. That night we were called by the CO of the unit Rupcic and gave as the following order:

- At dawn tomorrow morning you will patrol over the border part Vrsac-Bela Crkva where German tank units from Romunia are anticipated."

A member of these tank units, a tank gunner, describes the Major Diner StG 2 attack on a mountain pass fortification:

"A fine coating of dew covered the vehicles. Only a thin strip of slowly lightening sky above the mountains heralded the start of a new day. It was 5 am on the morning of 6 April. We looked at our watches. Fifteen minutes to go. As we adjusted our binocular, a pale dawn light started to seep down the hillside in front of us. The mountains behind rose out of a milky white morning mist. One more minute. There! To the west a machine gun rattled briefly. Then a muffled explosion. A few seconds of complete silence, then the whole front erupted into noise. Our own light flak units added to the din of the artillery.

Despite the racket, my ears picked up the thin drone of aircraft engines, growing louder every second. I knew from experience what it was, and pointed the glasses upwards. Sure enough, the dim shapes of approaching Stukas. Now they were circling above us, the dark red pin-points of their position lights plainly visible beneath the shadows of their wings.

They slowly began to climb, breaking into the clear light of the new day. More and more aircraft joined them as they headed towards the ridge of the mountains immediately to our front. One last circle, as it to make double sure of the target below, and then the first Ketten went into their dives. Even from here we could hear the familiar nerve-shattering howl of their sirens. And then the first bombs fell. The tiny black specs rained down on the enemy positions. The noise of the explosions echoed back unseen clefts in the mountains as Staffel after Staffel attacked. Soon pillars of yellow-brown smoke were staining the pristine whiteness of the high snowfields."

While Stukas of StG2 were attacking enemy positions and Me 110 were attacking all airfields in the general direction of the attack, a large formation of bombers from II./KG 4, KG 2 and KG 3 was joined by the fighters from II/JG 77, III/JG 77 and III/JG 54. A Yugoslav fighter-pilot during the Zerstorer run said: "When we were watching, almost all, of our fighter airplanes burning our CO said:

- It really is war. We will get paid double".

The approach of the bomber formation to Belgrade went really quiet, and only when the noise of multiple aircraft engines was reported from the hills surrounding Belgrade JKRV's response late due to the failure of the early warning system.

Kapetan 2. klase Mihajlo Nikolic:

"In the morning 6. April 1941 I took-off as first, with my wingman Milodrag Boskovic to follow the order. We returned after 50 min, when we landed we started to eat some sandwiches when from the office burst our CO giving us the sign to take-off. When we were strapping in he radioed us that German airplanes crossed the border at Subotica and were flying from South to Belgrade.

The officer ordering Nikolic to take-off was the CO at Zemun-Adum Romeo. 16 planes took-off.

The first was the IK 3 squardon of kapetan 1. Klase, who was escorted by narednik Dusan Vujicic. The second pair consisted of kapetan 1. razreda Todor Gojic his wingman was narednik Milislav Semiz. Dusan Borcic was leading the third pair and his wingan was Bamfic.

Mihajlo Nikolic continues

The IK-3s flew first because they got the information earlier, we followed them with seven Me 109E (there were ten, but one was unserviceable, and two were on patrol).

It was a clear day with a bit of haze and scattered clouds so we flew towards Sava river. When we were in the air, I looked back from habit and I saw that my wingman Milodrag Boskovic in confusion forgot to pull in his landing gear. I called him via radio but to no success, and only when I opened my landing gear, he cleaned out his gears and joined fighting formation. At first we saw nothing, then we spotted our planes diving into something. When we got closer, the sky immediately went black from German airplanes, and we flew into this turmoil not ever dreaming that Germans had an umbrella of fighters above us. First we saw the Stukas flying in groups of seven. There were so much targets that we didn't have to chose anything. I attacked one group from the left and bellow, but immediately the right side of the group descended for the gunners to have a clear shot. This was a trained tactic, but the group didn't break. We made a couple of runs, but didn't pay attention if there was any results. A little later I noticed that a Stuka was starting to burn, The group immediately-as being ordered-broke fearing an explosion.

Then I noticed that the He 111 were coming. I made a turn and told Boskovic that we are going for a group from behind because they are defended from the top and bellow. I started my attack carefully choosing my position, all concentrated in aiming...from nowhere a blast in the cabin and a German fighter almost rammed me with his wing, coming from the left.

My wingman didn't even saw him. That fighter got a good shot in me, but I to squeezing the trigger gave full left rudder and fired at him. The cabin was already filled with smoke. The fuel tanks are behind us and they could catch fire, we were told to put the fire out with a quick dive, I managed to do that, but when I wanted to apply throttle the engine did not respond. I don't see or hear Boskovic (I never saw him again). I started to chose where I will land, and between the villages Sakule and Baranda I notice a clearance with some stock on the left and right a field. I chose the field and I belly-land. I open the cabin and I notice there is blood on my flying suit, I got shot in my left leg."

In fact Boskovic wasn't found until 1955, when he and he's Me 109 were recovered from Dunav river near the village of Kovilj which is about 2min flying time in general heading towards Belgrade to the place that Nikloic crash-landed his Messerschmitt. Some parts of his Messerschmitt are kept in the Yugoslav air force museum, including the DB 601 engine.

The other pair of JKRV Me 109's were Miloš Žunič and Džordžem Stojanoćem.

The pair closed in on the He 111's, one bomber was shot down by Žunič. The pair quickly turned to the fighters and defended themself untill they ran out of ammo. Me 109 flown by Žunič was hit a couple of times, and he bailed out. He came to earth dead. His wingman survived.

The flight of IK-3's lead by the talented aerobatic champion and flight instructor Savo Poljanec from Maribor soon reached the first wave of enemy bombers.

Poljanec lead the group on to the bombers but they were seperated because of the German Me 109 diving on them. Poljanec was now alone and fighting with the guns of 27 bombers. The experienced aerobatic pilot made an immelman turn and came back down the side of the formation concentrating on the right bomber of the last three. Just before the bomber was engulfed in fire the tail gunner watched the victorious Poljanec climb over the formation. Then on the alititude of 6000m Poljanec noticed that a formation of German Me 109 fighters were preparing an attack on him. Poljanec evaded the first fighter, and then started a high speed pursuit, with a couple of short bursts from Poljanec the Me 109 began lossing altitude and was aparently out of control. His joy was to be shortlived because in the next moment, he was attacked by the next fighter who was following him closely all this time. Poljanec felt a sharp pain in his right shoulder and his engine started to quit. Seeing there was no point of proceding, he shut off his engine and started spinnig. The trick worked since the enemy fighters sure of their kills started climb again. His spin became uncontrolled now and only his great experience as an aerobatic pilot enabled him to exit this spin, and this only at minimal altitude. Poljanec was now flying his bullet ridden IK 3 towards Zemun trailing a glycol trail behind him. Just before landing he was strafed by a Me 110 and one of his shell exploded behind the seat that Poljanec was ocupaying. But all in all he managed to land safely and was immediately put in hospital.

Worth mentioning here is that Poljanec in a IK-3 flew a lot of mock dogfights against Yugoslavian Me 109E usually flown by Boris Cijan.

Over another part of Belgrade, over Senjak the second pair consisting of podporočnik Borčič and Bamfič, was looking for a good fight, but they didn't find any enemies, so they separetad to increase their chances.

Borčič flew toward the Rumanian border and then returned to Belgrade. Over Zvezdara he caught up with 20 Do 17's enemy bombers that was heading towards the centre of the capital. He attacked the last three and sent one Do 17 in the Danube river. The same scenario as happaned again as with the Poljanec. The German Me 109's were diving on him, but Borcic gained just a spot of advatage, so he could shot down a Me 109E. Now he was alone, and German fighters were trying to encircle him, but they weren't suceding untill Borcic run out of ammo. He was shot down on the banks od Danube 15km nort of Belgrade. His last fight was observed by a lot of spectators in Belgrade city. After the war the remains of his IK 3 was lifted from the river, and it revealed that no big 'white 10' was worn on the fusleage, but just a little 'black 10' on the rudder.

His wingman Bamfić was also fighting with the Me 109s over Batajnica. His IK 3 was alo badly damaged, and he was coming in for landing, but was bounced by two Me 109s. To avoid certain death Bamfic was forced into a series of steep turns, with his wingtips almost touching the ground. He crash-landed near the airfield. His IK 3 was completly destroyed during the landing, but Bamfić was not hurt.

Vujičić had to return to the airfield due to cooling problems.

The pair Gogić and Semiz shot down a Stuka.

A pilot of the bomber stream piloting one of StG 77 Stukas was lucky to avoid Yugoslav fighters:

"After the Green hedgerows of the Normandy countryside, the warm browns and greys of the local landscape were still unfamiliar to our eyes. The morning sun was glinting off the peaks of the Transylvanian Alps at our backs as we were approaching the unmistakable silver ribbonod the Dunav, the frontier between Rumania and Yugoslavia. The hazy outlines of a large city appeared in the distance-Belgrade!

Below us the first few burst of enemy flak. But nothing to worry about. Those of us who'd been through Poland and France had seen much worse. The city is much clearer now. The white tower-like buildings bright in the morning sun. The Staffeln opens up as pilots prepare to dive. Our target is a the fortress which gave the city it's name. Perched high above the promontory where the Sava joins Dunav, it couldn't be missed.

I felt the jolt as our bomb was released. We leveled out and turned back for base at high speed, ready to prepare for the next mission. As we retired I saw the fortress ringed in smoke and flames. Fires had also been started in the royal palace and the nearby main railway station. Soon smoke hung over the whole city like a great grey shroud.

On 6 April 1941, during the first mission of Luftwaffe's I.(J)/LG 2 - low-level attack against the base of the 36th Fighter Group base at Rezanovacka Kosa at Kumanovo shortly after 6:00 am - the Bf 109s of this unit got involved in a dogfight with the Hawker Fury biplanes of 36th FG above this airfield. Without any reported losses, I.(J)/LG 2 (equipped with Bf 109 E-7) made the following claims of Hawker Furys: Lt. Geisshardt - 4 Furys (victories Nos 14-17), Olt. Clausen - 3 Furys (Nos 6-8) and Gefr. Quatember - 1 Fury (No 3).

During the first mission of JG 77 - escort to the raid against Belgrade - between 07.30 and 08.40, 56 Bf 109 of JG 77 were involved in furious dogfights with Yugoslav fighters. Oberleutnant Erich Friedrich of Stab/JG 77 claimed a Yugoslav Bf 109 as his third victory. In II./JG 77, the following pilots claimed one Bf 109 each: Olt. Jung (his victory No. 3), Ofw. Petermann (7), Lt. Zuzic (1), Fw. Ftröba (3), Olt. Patz (1), Fw. Köhler (2), Ofw. Petermann (8). And - in III./JG 77 - Olt. Schmidt one Bf 109 (No 1) and Ofw. Riehl one Ikarus IK-2 (No 2). No losses were reported by JG 77 during this mission.

After a short brake with some refreshments Yugoslav pilots, anticipated the next raid on Belgrade between 10 and 11am.

Under the command of Gogić now six planes took off. They attacked the bomber formation, but the resistance was much better then during the first raid. The Me 109E flown by Karl Štrebenk a native of Zagorje on Sava river, was badly damaged, but Štrebenk was able to land safely. After landing he discovered that his airplane was had 80 bullet holes. Determined to get his revange, he begged the CO which was Rubčić at the time, to let him use his plane to go and pursue the Germans. After a short argumnet since Rubčić said that it was no point as the Germans are already attacked by the fighters from Prnjavor, but all in all Rubčić allowed Šterbenk to use his plane. Štrbenk flew right in the gagle of German and Yugoslav fighters. The Germans noticed the special marking carried on the CO's plane so they concentrated all the eforts on Štrbenk. With the combined efforts of the pilots with well over a year of constant fighting. Šterbenk stood no chance. He crashed on the Glogonjski rt.

During the second mission of JG 77 - low-level attacks against the Belgrade area - Lt. Omert claimed a Bf 109 (No 1), while another eight Yugoslav aircraft were claimed destroyed on the ground. During the same mission, Olt. Hans-Ekkehard Bob of 8./JG 54 claimed the only victory by that unit - a Bf 109. During this mission, Olt. Heinz Duschle was shot down by ground fire and crash-landed in Yugoslav territory. He was hidden by German Yugoslavs and later returned to his unit. No other German BF 109 was reported lost during this mission.

I.(J)/LG 2 flew another five low-level attacks against airfields in the Niš area during the day. Three of its Bf 109 E-7 were repotted shot down by ground fire.

During one low-level attack against the Yugoslav airfield at Laibach, the Bf 109 piloted by Oberfähnrich Hans-Joachim Marseille was hit by AAA, but Marseille managed to return the aircraft to base.

The CO of the 142 eskadrile 32. vazduhoplovne grupe 6. lovackoga puka Milutin Grozdanovic also took-off from Prnjavor airfield with his Me 109 with code number 52 that morning:

"At 6.30 we were overflown by a large formation of German bombers. There was more then hundred of them. When we saw this we immediately jumped in our aircraft which were ready from three o'clock in the morning. We took-off and followed the German formation in pairs. We caught up with the German formation in 2 -3 minutes. Me and komandant grupe Danilo Djordjevic, Bozidar Ercigo and Radoslav Stamekovic attacked the bombers. There was so much bombers that we attacked a bomber each. We had two cannons and two machine guns.

We flew over them then we dived and tried to get as many hits as possible in the bombers cabin. We attacked one bomber after another until we spent all of our ammo. Then we dived to the treetops and escaping enemy fighters and one by one returned to the airfield. We didn't even pay attention if we had shot-down somebody and after the attack we didn't have any losses.

After a short break at about 10 o'clock we flew again and again attacked the bombers. There were so much bombers some returning from Belgrade some flying to,my god there were so much bombers. When I was returning I saw a group of 60 - 70 Stukas. I separated from my group and attacked them because I was faster and had more ammo. I closed in to 20 - 30 meters so I didn't even have to use my gunsight. We had so high goals we didn't even watch if we shot-down somebody, we just kept attacking till our ammo ran out. When I run out of ammo I made a low-level escape to the airfield to reload the airplane and to give others a chance to fly."

The JKRV's communication system was insufficient so that some squadrons didn't even know about the war. Blenheim's pilot Ivan Miklavec, a member of 8. bombardeski pulk 215. eskadrile stationed at Topoli explains:

"A solider slams opens the door and starts screaming at us: - Did you hear? Belgarde was bombed...The Germans attacked us!

I stood up and asked: - Who told you that?

- Radio Belgrede we heard it on the Caproni ( the only radio was in one of our school Caproni).

Then in a second the airfield came alive. Alarm! Airman in readiness, mechanics, bombs, ammunition!!! Short commands resounded. I look up in the clear Sunday sky, in to the sun-the blood is boiling in our vanes. After the first salvo of orders and news there is silence. Everybody is doing their work and preparations without much speaking.

Sunday, the first war day passed in take-off readiness just in case we were attacked. We loaded our planes with 100 kg bombs and with machine gun ammo. In the afternoon the first two machines took-off at 13.30 with a recon mission over Graz. They bombed a station in the way back and returned safely.

At 5 o'clock in the afternoon we received the order for take-off, but regretfully for tomorrow. Komandir Jovičić explained the mission for us, we were to bomb road and railway bridges around Klagenfurt. Jovičić surprised us by saying: We don't have much ammunition, but we will use the one we got the best we can. To make sure the bombing is accurate and to avoid enemy fighters I suggest that we attack at 300m. Do you agree? We all accepted the dare suggestion. At 20.30 we were surprised by another mission order, the first was called off. We were to bomb the a railway section and station Feldbach in Austria. Take off before dawn, we were to meet at the airfield at 3 o'clock in the morning. So tomorrow is the day..."

Ivan Miklavec describes his story later on, but for most of the pilots 6. April was the day.

The mission against Graz railway station was executed by the best JKRV bomber pilot Karl Murko.

The group commander ordered Murko to head straight to Maribor on the altitude of 2500m, then follow the railtracks to Graz. From the height of 300m he should drop his four 100kg bombs onto the railway station.

His mechanics checked his Blenheim and loaded it with bombs and amunititon.

The Blenheim was piloted by Murko, his gunner was Malešić and the bombardier was Pandža. They took off at 13.30 in the afternoon.

Murko didn't agree with the route he was ordered. He flew towards Maribor at the height of about 300m, He then turned towards Austria and then proceded uo the valley of the river Raba. When he overflew the railway crossing Gleisdorf, he descended even lower, so he was virtually huging the ground. He was sure that if he was higher he would be spotted by the AAA and fighters from Thalerhof (Miklavec proved this was right-see the second day). Without any resitance he closed into the suburbs of Graz and climbed to 700m. With the railway station in sight, he put his Blenheim in a shallow dive to increase his get-away speed. He released the bombs hitting the tracks with two bombs, the third demolished a building with food suplies and the fourth one missed. Just before reaching Maribor Murko was attacked by a German Me 109E, but the shots from the gunner Malešić and the low flying by experienced Murko prevented the Me 109E to get any real hits. The Me 109E probably low on fuel turned for home. Later mehanics discovered only 2 7.7mm holes in the tail of the Blenheim.

Another known pilot was shot-down that day. Knight cross holder Oblt. Herbert Ihlefeld was brought down by Yugoslavian AA. The pilot landed near Nis, and got slight head injuries.

The Germans continued their attacks against Belgrade through the day and till about 11 o'clock in the evening. Four hours later narednik Miklavec woke up.

"7. April 1941. We all woke up at 3 o'clock in the morning. In the dark backyard splashes of water were heard, the well pump was quickly filling the buckets with water for refreshment. A bus drove as from the village to the airfield in pitch darkness carefully following the blackout regulations. At the airfield komandir Jovovic repeated the mission, refreshed all agreements and we all started to dress for the flight. We didn't get any meteorological report. At 4 o'clock in the morning we were ordered: To positions! Start the engines! A quick salute to the CO. His last words were: The time has came, either to strike as warriors or to die! We all separated into the night each in the general direction of his aircraft.

The mechanic with his soldiers was already there. The formation was starting their engines, the noise was tremendous. I checked my aircraft, walking around it with a flashlight. I was stunned, the lower wing surface had multiple bayonet-made holes. So, sabotage... I didn't notice any other damage, so I didn't report it. I thought that I could do it after the mission. I also checked the four bombs and unscrewed the igniter half a turn each. I presumed we would have to fly low. When I entered the cockpit I found out that somebody broke the clock in the aircraft. I didn't have the time to find out who did it so I borrowed a wrist watch from the first man who walked past. The crew included a pilot, mechanic/gunner, and bombardier/navigator/aircraft leader (me), we didn't have any radio operator because we didn't have the radios installed yet. One by one all of our 28 aircraft took-off in pitch dark, only a small signal light blinked the take-off command in one minute intervals. I counted the take-offs ...five ...six ...seven ...we were number ten. But where is my pilot? I am waiting, he should be here minutes ago. Mechanic leans out of the cockpit and asks the closest solider if he has seen him. Nothing... number eight is already rolling... I order the mechanic to close the cabin, we will fly alone. I check both engines again, everything is OK. Then I hear knocking on the cabin. The pilot boards the plane in the nick of time. The cabin is closed again. I am looking for the light signal. Here it is! Let's go.

A unpleasant felling of dampness surrounds us at 700m. I quickly notice the first meteorological information-clouds. I order the pilot to climb, because we are flying above 600m high mountains, and my map is telling me we are flying towards even higher mountains. My pencil marks the already flown path of our Blenheim. The pilot asks me where we are. I answer him: Varazdin is to the right. Our altitude is 1500m. It will be dawn soon, and I think we are flying in upper cloud levels so I order to climb to 1700m. The success is obvious as we brake the clouds. I am scanning the sky to spot the others who took-off before us. Far below us I spot a white dot-it's a plane. We are quickly catching him, I recognize him he is one of ours! We are closing in, I want to see the commander, but the airplane signals us the sign.

Watch it! it waggles its wings and makes a U-turn and flies back from where it came from. When he disappears I start to wonder. Did they receive the command for return, was it the whether. Without the radio receiver I didn't get the answer to any of those questions. Soon after we cross the border my mechanic shakes my shoulder and screams There are two fighters in combat above us, one of them is ours. In a moment we lose sight of them (that could be the two JKRV's Me 109 in combat with a German one above Maribor). We have reached our target, far below us, in the valley surrounded by hills we don't see it, it is hidden by the cloud base, our recon won't do us much good. I calculated another 6min before we make the U-turn. We start to sink in the clouds, we are waiting for results of our cloud braking, if I miscalculated...we dive to only 400m. Then we brake through, firs we see something dark brown, then fields, than houses. We fly over a road at 300m. Raindrops are banging on the windshield and are obscuring my sight. I notice some dark transport vehicles driving south, we are going that way too. Feldbach must be somewhere on the right side. I am looking for the railway. I set the bombsight, triggers, electric button. We passed over the road again, we still don't see the railway, then a bright line flashes-a river, a bridge bonds both sides with a road. I show the bridge to the pilot. We fly over the river and make a turn.

Another glance to the bombsight, I press the button, the plane climbs a little and makes the turn. The old bridge is gone only a couple of beams are left. 100m ahead two transport cars stopped, they won't get over the bridge! Then the valley closes in, then opens-up again. Look there is the Feldbach station, we fly over the station at 200m, no traffic, no defense, they even removed the stations name. I press the button and the second bomb parts from the aircraft. After the turn we notice a full hit on the tracks an railway crossing. After a while my mechanic screams: Airplane! and shows me a little dot on the right. When we close in to 300m a recognize the shape, the yellow band, the black cross...no doubt Stuka!!! Machinegun! a yell to the mechanic who is already in the machinegun turret. We close in to 30m and they spot us. In that moment our machine gun sings it's mortal song three salvos 50 bullets each, and the Stuka rolls over an disappears in the clouds. First victory...We won't be taken easily. We fly over a 900m high hill, then we spot barracks lots of them then a warehouse then a railway more barracks. I drop the fourth bomb on this establishment. I latter found out I bombed the wings assembly plant in Wiener Neustadt.

When I was ready to order the plane back I saw a main road leading to Vienna. I dropped my last bomb there.

Then my mechanic screams: - Enemy fighters!

... I turn around, yes four fighters on our tail. I order the pilot to climb into the clouds a turn right then after a minute a turn left to previous direction. I quickly calculate the heading from Vienna to Maribor. We turn our trusty Blenheim in that direction. Then we literally fall out of a cloud and we see the Wiener Neustadt airfield full of aircraft!! The temptation was just too big so we made a low pass our machineguns spiting death. Then came the Flak... But the worst was yet too come we had to fly over a hill 900m high we were flying at 300m. We have to make a circle to gain height over the airfield, the flak was ready for us. We took multiple hits and escaped in the clouds. It is getting lighter, I suddenly hear the engines coughing and spiting, I check the gasoline level...30 liters...the pilot immediately cuts down the throttle to save gas. What now? We had 400 liters seven minutes ago, the fuel tanks must be hit. The pilot and mechanic ask me:

- Shall we jump?

- No! Steer 30° to the left!

(I choose to crash-land because our Yugoslavian made Blenheims didn't have the emergency hatch, our CO had a simple explanation: No jumping. These machines cost 5 million dinars each.) We gave up hope to reach Yugoslavian soil. Only 400m left we brake the cloud base and start looking for a place to land. There on the left below that hill, the crash-land is possible only there. We will plug our nose in, but we have no choice, pilot pulls out the flaps, and I the gears. We are flying with speed 230km/h. The wheels absorb a strong blow, full throttle, the earth bounces, I am not strapped in so I grab for my harness at the last second, a nose blow, the cabin crashes, I am thrown out of the seat...over.

I don't know how long we just lay there, not unconscious but we just lay there. We crawl from our positions and we check if everybody is all right. We climb on the wing and we pet our giant Blenheim N°25 who saved our lives with his destruction.

This is the start of the story about a Yugoslavian war captive Ivan Miklavec, who latter wrote a book "Skozi deset taborišč". ("Through ten prison camps").

While Miklavec was laying in Austria, the Belgrade defenders had their hand full.

After a early morning briefing it was decided that the JKRV pilots would fly in five plane formation, since the pairs didn't enable to act more agressive.

The first group of five Me 109 scrambeld and attacked a small group of Stukas.

The group lead Grozdanović acompanied with Ercigoj, Grozdanović, shot down the leader of the Stukas while other fighters protected them. The Stukas droped their bombs and ran for the border. A group of German fighters apeared, but they didn't attack.

In the morning Karl Murko tried his luck again with the target of Segedin airport in Hungary. The 68. Vazdušna skupina this time flew in formation and was intercepted soon after crossing the border. Murko was leading a element of three planes and sucesfully evaded the fighter ambush. But latter on when he was returning from the mission his plane now alone was attacked by a pair of Me 109's. They scored a lot of hits, but didn't hit any important parts of the aircraft. Then a cannon shell bounced off the cockpit greenhouse and exploded only meters away shatering the greenhouse. Murko now had a tough time controlling the aircraft, and set it on a glide-like path towards Romunia. The trick worked since the fighters changed course.

After a few minutes murko set course again for Yugoslavia. Over Bosanski brod, he was almost shot down by Yugoslav AAA. Murko managed to land safely though.

In the afternoon the Me 109's again acted in the five planes formation. Again a small group of Stuka overflew Fruška Gora, they reportedly shot down two Stukas, but then the escorting fighters started to apear in great numbers. The fivesom, had a tough time defending themselves. They were low on ammo, so they started to head back to the airfield. The first to land was poročnik Kešeljević. Just about then the asistant CO of 103. eskadrilje Miha Klavora from Maribor was preparing to take-off he exchanged a few words with Kešeljević about the situation in the air, and immediately after that Klavora and his wingman took off to aid their friends.

The sun started to set, and two more fighters came in for landing with Vilim Acinger and Ivo Novak.

Then the voice of Klavora resounded over the speaker.

This is Klavora. I am out of ammo.

He shot down an enemy fighter, but was still fighting with two other. Now out of ammo, he fought a desperate batle with time, hoping at the same time that someone from the airfield would come to his aid.

The only aircraft ready for combat was CO's Džordževič's machine. He walked very slowly toward his aircraft, stood on the wing and then turned back to the barracks, explaning that the parachute wasn't ready. It was obvoius he had no intention to fly.

One of the attackers over flew the airfield strafing, Klavora tried to take his chance to land, but the other fighter caught up with Klavor and poured a steady stream of fire into the aircraft of brave Miha Klavora. He crashed on the Sremska ravnica.

Just after that one of the enemy fighter with his pilot was obviously wounded and crashed into Fruska gora.

All in the field knew very well, who was to blame for the death of the brave native of Maribor.

Milislav Semiz didn't have a peacefull day since he around 17.00pm attacked a formation of three bombers, in this attack his IK-3 took 56 hits, 20 among them in the engine and airscrew, but as Poljanec the previous day he managed to land safely at Zemun airfield.

The second day brought a little pause in fighting, so the chain of command and organization recuperated after the first shock, Mile Curgus explains:

I was more a spectator then an actor in the April war. I was a kapetan 2. klase, fighter-pilot 2. lovackog puka. On 2. or 3. April I was given an order to go to the Knic airfield and to prepare all necessary for the arrival of the puk from the Kraljevo airfield. When I arrived at Knic I was notified that I was transferred to Belgrade to help defend it. When I was travelling we were told that the Germans attacked Yugoslavia. The train stopped and we didn't start to move till 7. April in the morning. The first train from Nis to Belgrade got to the city at about 7 o'clock in the evening, the train wasn't able to get in the station so it was redirected over the bridge to Zemun. I immediately went to the JKRV's command, and there I find only two artillery soldiers guarding the building. I walk a couple of kilometers to the Zemun airfield. I ask somebody about the location of the command, and he shows me a bunker, a large cement pipe. There was the Stab brigade and komandant, pukovnik Rupcic. I reported to him and he ordered me to remain at the airfield (it was the same Rupcic that ordered Nikolic and Boskovic the unsuccessful border dawn patrol two days earlier).

The 7. April battle report came with a special message. Today at about 11 o'clock in the morning one of our pilots in Me 109E chased a group of 18 Stukas, and managed to get two. But he to fell in flames at Krcedin in Srem. We found a watch on the hand of the pilot on which there was a special engraved message: For the champion of the First pilot school in 1939 vazdusnim purucniku Zivici Mitrovicu-the Rogozarski factory."

The second day of the war wasn't so active because the Germans didn't continue so strong bomber offensive, their goal was achieved. German reconisance planes discovered the 32. group airfield, and airfield Belgrade was constantly under attack, it was decided that all fighters should transfer to Radinci airfield. If all fighters weren't able to follow the command, they should join the main bulk at Radinci on 8. April in the morning.

Komandir Milutin Grozdanovic had a definitely spoiled day:

"In the afternoon I was given an order from the komandant Bozidar Kostic to transfer to an airfield near the village Radinci, because he feared that our airfield was discovered by the Germans. I was very tired, and when we got over Radinci, I tried to land first, I lost too much speed, stalled, flipped my wing, and crashed. I turned over and got serious injuries. Unconscious I was transported to a hospital in Sremska Mitrovica, after 7-8 days the Germans came and treated me. When they found out that I was an officer and that I put up a brave fight, they treated me with respect, and after 15 days I was accompanied by two medicals to Belgrade, where I finished my treatment."

Between 09.15 and 10.40, JG 77 flew low-level attack missions against airfields to the south of Belgrade and escort to Stukas. Two aircraft were reported destroyed on the ground. No losses were reported by JG 77 on this day.

8. April (day 3)

The weather was very bad on this day. Clouds and light rain. The 2 surviving IK-3's on Veliki Radinci are joined by the prototype of the IK-3 series II. This airplane had the oil coller reshaped and modified, so it was 25% smaller as the ones on the series I aircraft. The prototype also had the modified exhaust stubs with propulsion effect. This two changes helped to increase the airspeed to 582km/h.

The day also prevented the top Yugoslav bomber ace Karl Murko to get to Zadar. His CO ordered him to take the squadron's liason bucker jungman and to reconitre if there are any Italian targets worth destroying. About halfway there he turned back due to bad weather.

An IK-2 from Bosanski Aleksandrovac chased what seem to be a reconnissance aircraft but to no avail. One IK-2 crash landed on the same day leaving only 7 IK-2 servicable.

A very sucesfull mission was flown by 66. and 67. skupina from Mostar flying the heavy S-79 bombers. They set off in formations of three planes. One three plane element was leading an S-79 flown by Viktor Kiauta, the gunner was Ivan Mazej and bombardier was Terček a native of Ljubljana.

Soon after the element overflew Uroševec, Mazej noticed 5 Me 109's closing in on the rear quadrant. The element tightned the formation and this fire power preveneted the Emils to get any hits. After a few attacks, they returned to their previous direction.

The flew in the valley of Kačinska klisura, where a large amount of troops and vehicles were situated preventing the retreat of the Yugoslav forces into Crna Gora (Montenegro). Terček began releasing the bombs in steady intervales. And so did the other two aircraft in the element. Despite heavy AAA the combined effort of the three planes, resulted in a desctruction of 10km long column of vehicles and infrantry, two bridges and a section of a railway track. This action prevented the advance of the Germans into Kosovo polje. They had to took a more safer route over Kraljevo and Čačak.

This little known action is regarded as the most sucesfull mission flown by JKVR during the April war.

9.April (day 4)

The airfield that was ocupied by the Blenheims from 3. Bombarderskog puka suffered heavy strafing by Me 109's even in the most disastruss weather. The secret of such a sucesfull navigational feat of German fighters was soon revealed since they found a radio-navigational device in a neighbouring monestary that was leading the German fighters.

At about 2 o'clock in the afternoon IK-2's from Bosanski Aleksandrovac took off chasing a few observation machines. Later on 27 Luftwaffe Me 109 straffed the airfield. Eight Huricanes and five IK-2s took off to intercept the German raiders.

Poručnik Branko Jovanović was now confronted with nine Me 109's around him. Skilfully using the extreme manouerabiltiy of IK-2 fighter managed to stay out of German gunsights. After the battle two German fighter were found burning on the ground along with two Hurricanes and one IK-2.

The bulk of the fighter force now stationed at Veliki Radinci was still grounded due to bad weather.

The weather prevented any further flying untill 11. April

11 April (day 6)

Milislav Semiz now flying the new and fast 2nd series IK-3 caught up and shot down a Me 110C-4b over Fruška Gora.

Aroud 2 o'clock in the afternoon 20 Me 110 strafed Veliki Radinci. Two IK-3 flown by Gogić and Vujičić with four or five Me 109's took off and in the short fight shot down two German planes. The victors over the Me 110 seem to be the two IK-3 pilots.

12 April (day 7)

Before the war the main figter school was based in Mostar, and the planes were of mixed type.

After the first few days of the war only two were left, a Me 109 and a Hurricane.

A infrantry colonel asked if someone from fighter school could fly over to Imotski and find out if the Germans are already there. Two pilots Franjo Godec and Stipčič took off. Godec was flying the hurricane this time. Half way there Godec spoted three Me 110's below heading towards Mostar. Fliping vre his wing hoping Stipčić would notce the Germans too, Godec attacked the Me 110 now flying in the Mostar valley. Even though his bursts met their target, the Me 110 just kept flying. In the heat of the battle Godec didn't notice that the other Zerstorers were gaining on him. He wanted to fire another burst, but he ran out of ammo. Exactly in this moment he was hit by a ignition cannon shell. The cockpit was immediately filled with thick black smoke, preventing Godec to breath. But he was determined to get that Me 110. He tried to cut off the tail of the fighter with his airscrew, but luckily the Me 110 started spinig before Godec reached ramming ditance (this type of the attack was latter known as Taran). He slamed the Me 109 in half loop opening the cockpit at the same time. He bailed out, only to be slamed with his back to the tail surfaces of his fighter. After buncing off the aircraft he opened his parachute. The strong wind was now carring toward Mostar city. He touched down at Jasenica village, but was dragged for a long distance before being able to cut off his parachute. He had a broken leg and a spoiled flying day, but was othervise OK.

Yugoslavia was in it's Extremis. Like a mortally wounded quarry set upon by a pack of hunting dogs , she was now under attack from all sides. The weather deteriorated during these days there was almost constant rain snow and strong wind. There was a number of aircraft that tried to get airborne, and there was a large number of accidents too. The Germans that had little to stand in their way now, eased off the air-pressure on the Yugoslavian soil. The Stuka Jagd units wit fresh instructions from the C-in-C General Lorh diverted their attention to Greece.

Mile Curgus describes the last free days best: "That days the situation was unclear. We transferred to Radinci. Chaos in Mitrovica, rain, light snow, cars, wagons, trucks, horses, shouting screaming, real war situation! I arrive on the airport, then I find out that our borders were crossed. In the morning, it was maybe April 12, rain-we can't fly. There is nothing left to do for us, but to burn the planes. Djordje Keseljević shouts;Who's got a match? Nobody but me has it, but I cannot be the godfather of this fire. In the end I gave my match after all, which set our fighter, our pride, our possession afire. When we were watching them burning, we were relived of our flying duties. The retreat has begun, the Germans were advancing very fast, and we were on our own. Sooner or later we found ourselves on the German war transports going to prison camps."

But there was one more action for the airman to execute, before they fell into enemy hands. After the separate piece talks fell through, the King and his was in the danger of being captured. The only way out of the country was by air. Onlooking that goal the rest of bombers, transports and fighter were directed, to the Niksic region. On 14. April the evacuation begun. First a Savoia bomber took-off with the King Peter II, on the next day the government and some organizers of the uprising were transported to safety. The only fighter umbrella for this airlift was a sole Hurricane making a race-track pattern to cover take-offs, and 7 Hawker Furys on standby. After all the airlift was efficient enough to get the most important persons out of the country.

A line about the April war and the participating Yugoslav pilots goes:

On 27. April 1941 the fallen heroes shouted: BETTER WAR THEN THE PACT.

Falling from the skies ten days latter they whispered with their last breath: BETTER DO DIE THEN TO BE A SLAVE.

They did lose, but they fought for their country-and so did the Germans, and that makes them heroes, every one off them who dared to take-off on a bright April day...

Yugoslav Royal Air Force - RYAFRoyal Yugoslav Air Force (JKRV and VVKJ)

Bristol Blenheim RYAF destroyed by Bf 110's from II./ZG26Blenheims:

- Bristol Blenheim Mk.I, no.3548

- Bristol Blenheim Mk.I, no.1/166

- Ikarus B4, Br.3535

Capronis:

- Caproni Ca-310, No.2

- Caproni Ca-310bis, No.15

- Caproni Ca-311, no.28

Dorniers:

- DFA Dornier Do-17Ka-3 (Kb-3), no.3363

- DFA Dornier Do-17Kb, no.3363

- Dornier Do-17Ka, no.2

- Dornier Do-17Ka-2, no.3333

- Dornier Do-17Ka-3, no.3347

Savoias:

- Savoia Marchetti S.79K, no.3705/9

- Savoia Marchetti S.79K, No.3728/12

- Savoia Marchetti S.79K, no.3741/13

- Savoia Marchetti S.79K, no.3702, Egypt 1941

Messers:

- Messerschmitt Me-109 E-3, no.2307, L-07

- Messerschmitt Me-109E-3, no.2508/8

- Messerschmitt Me-109E-3, no.2508, spring 1940

- Messerschmitt Me-109 E-3, no.2310, L-10

- Me-109E-3, VVKJ no.2511/11

- Messerschmitt Me-109E-3, no.2521

- Messerschmitt Me-109 E-3, L-26, no.2526

- Messerschmitt Me-109 E-3, no.2530, L-31

- Messerschmitt Me-109E-3, no.2532

- Messerschmitt Me-109E-3, no.2551, summer 1940

- Messerschmitt Me-109 E-3, L-80

Hurris:

- Hawker Hurricane Mk.I early, no.2306

- Hawker Hurricane Mk.I (early), no.2306 (white VI), spring 1940

- Hawker Hurricane Mk.I (early), no.2308, spring 1941

- Hawker Hurricane Mk I early , no.2310/X

- Zmaj Hurricane Mk.I, no.2317

- Zmaj Hurricane Mk.I, no.2347

Furies:

- Hawker Fury Mk I , no.1/90 Hawker Yugoslav Fury II, no.2219/54

Locals:

- Ikarus IK-L1, prototype

- Ikarus IK-2, no.2110/2

- IK-2, no.2104

- Rogozarski IK-3, no.1

- IK-3, no.2158/8

- Rogozarski IK-3, no.2159/10

Liaison:

Taifun:

- Messerschmitt Bf-108B, YU-PFC

- Messerschmitt Me-108B-1, no.774, autumn 1939

- Messerschmitt Me-108 B-1, Sh-02, summer 1940

- Messerschmitt Me-108 B-1, Sh-07, 1940

- Messerschmitt Me-108 B-1, Sh-07, 1940

Storch:

- Fieseler Fi-156C-1, no.802/20

- Fieseler Fi-156C-1, no.7, spring 1940

Transport: (Mostly civiliam planes pressed into military service)

- Lockheed L-10A Electra, Aeroput Liner, YU-SAZ

- Lockheed L-10A, ex-Aeroput, Egypt 1941

- de Havilland DH-89 Dragon Rapide, YU-SAS

- De Havilland D.H.83, UN-SAK

- Rogozarski RWD-13S, no.754

Seaplanes:

- Dornier Do J II Wal, no.251

- Dornier Do J II Wal, no.256

- Dornier Do J II Wal, no.260

- Dornier Do-22 Kj (Do H), Aboukir Bay, Egypt 1941

- De Havilland D.H.60G, 'Sarajevo'

- Zmaj Heinkel He-8, Crete, Greece 1941

- Rogozarski SIM-XIV-H, Aboukir Bay, Egypt 1941

Trainers:

- Bucker Bu-131D, no.427/27

- Bucker Bu-131D, no.614/14

Various:

- Avia BH.33E SHS, No.1026/4

- Hawker Hind K9, No.3

- Potez P-631, no.2072 (evaluation example)

- Messerschmitt Me-110C, ex-LW (captured)

Web References: Aircraft Profiles here : http://allaircraftsimulations.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=95&t=12551&start=0&hilit=yugoslav

Three-Pronged Drive on the Yugoslav Capital

The British, Greek and Yugoslav high commands intended to use Niš as the lynch-pin in their attempts to wear down German forces in the Balkans and it is for this reason that the locality was important. The Yugoslav Supreme Command committed its reserves, including the 2nd Cavalry Division, but these were harassed by the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) during transit to the front.[2]

Fall of Belgrade

Italian occupation of Slovenia and Croatia

The Italian Second Army crossed the border soon after the Germans. The Second Army faced the Yugoslavian Seventh Army. The Italians occupied parts of Slovenia, Croatia, and the coast of Dalmatia.

After the establishment of the Liberation Front and the emergence of the partisan resistance, the Italian army's opinion has been in accord with the 1920s speech by Benito Mussolini: When dealing with such a race as Slavic - inferior and barbarian - we must not pursue the carrot, but the stick policy.... We should not be afraid of new victims.... The Italian border should run across the Brenner Pass, Monte Nevoso and the Dinaric Alps.... I would say we can easily sacrifice 500,000 barbaric Slavs for 50,000 Italians.... —Benito Mussolini, speech held in Pula, 22 February 1922[27][28][29]

As noted by Minister of Foreign Affairs in Mussolini government, Galeazzo Ciano, when describing a meeting with secretary general of the Fascist party who wanted Italian army to kill all the Slovenes: (...) I took the liberty of saying they (the Slovenes) totaled one million. It doesn't matter - he replied firmly - we should model ourselves upon ascari (auxiliary Eritrean troops infamous for their cruelty) and wipe them out'.[30]

The Province of Ljubljana saw the deportation of 25.000 people, which equaled 7.5% of the total population. The operation, one of the most drastic in the Europe, filled up Italian concentration camps on the island Rab, in Gonars, Monigo (Treviso), Renicci d'Anghiari, Chiesanuova and elsewhere.

Mario Roatta's 'Circular 3C' (Circolare 3C), tantamount to a declaration of war on the Slovene civil population, involved him in war crimes while he was the commander of the 2nd Italian Army in Province of Ljubljana.[31]

Italians put the barbed wire fence - which is now Path of Remembrance and Comradeship - around Ljubljana in order to prevent communication between the Liberation Front in the city and the partisans in the surrounding countryside.

On February 25, 1942, only two days after the Italian Fascist regime established Gonars concentration camp the first transport of 5,343 internees (1,643 of whom were children) arrived from - at the time already overpopulated - Rab concentration camp, from the Province of Ljubljana itself and from another Italian concentration camp in Monigo (near Treviso).

The violence against the Slovene civil population easily matched the German.[32] For every major military operation, General M. Roatta issued additional special instructions, including one that the orders must be 'carried out most energetically and without any false compassion'.[33]

One of Roatta's soldiers wrote home on July 1, 1942: 'We have destroyed everything from top to bottom without sparing the innocent. We kill entire families every night, beating them to death or shooting them.'[34]

After the war Roatta was on the list of the most sought after Italian war criminals indicted by Yugoslavia and other countries, but never saw anything like Nurnberg trial because the British government with the beginning of cold war saw in the Pietro Badoglio, also on the list, a guarantee of an anti-communist post-war Italy.[35][36]

In addition to the Second Army, Italy had four divisions of the Ninth Army on the Yugoslavian border with Albania. These units defended against a Yugoslav offensive on that front. Around 300 Ustaše volunteers under the command of Ante Pavelić accompanied the Italian Second Army during the invasion; about the same number of Ustaše came with the German Army and other Axis allies.[37]

Hungarian offensive actions