Bayon Temple

Name: Bayon Temple

Creator: Jayavarman VII

Date built: towards the end of 12th century

Primary deity: Buddha, Avalokiteshvara

Architecture: Khmer style

Location: Angkor Thom, Cambodia

Coordinates: 13°26'28?N 103°51'31?EFrom afar, according to Angkor-scholar Maurice Glaize, the Bayon appears "as but a muddle of stones, a sort of moving chaos assaulting the sky." From the vantage point of the temple's the upper terrace one is struck by "the serenity of the stone faces" occupying the many towers.

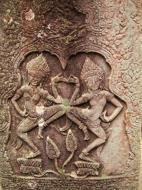

Built in the late 12th century or early 13th century as the official state temple of the Mahayana Buddhist King Jayavarman VII, the Bayon stands at the centre of Jayavarman's capital, Angkor Thom. The Bayon's most distinctive feature is the multitude of serene and massive stone faces on the many towers which jut out from the upper terrace and cluster around its central peak. The temple is known also for two impressive sets of bas-reliefs, which present an unusual combination of mythological, historical, and mundane scenes. The main current conservatory body, the JSA, has described the temple as "the most striking expression of the baroque style" of Khmer architecture, as contrasted with the classical style of Angkor Wat.

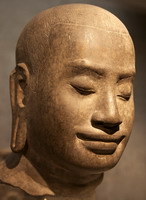

Historians find no coincidence that this portrait of King Jayavarman VII, located today in the Musée Guimet in Paris, bears a strong resemblance to the face towers of the Bayon. The Bayon was the last state temple to be built at Angkor, and the only Angkorian state temple to be built primarily as a Mahayana Buddhist shrine dedicated to the Buddha, though a great number of minor and local deities were also encompassed as representatives of the various districts and cities of the realm.

The similarity of the 216 gigantic faces on the temple's towers to other statues of the king has led many scholars to the conclusion that the faces are representations of Jayavarman VII himself. Others have said that the faces belong to the bodhisattva of compassion called Avalokitesvara or Lokesvara.

Angkor scholar George Coedès has theorized that Jayavarman stood squarely in the tradition of the Khmer monarchs in thinking of himself as a "devaraja" (god-king), the salient difference being that while his predecessors were Hindus and regarded themselves as consubstantial with Shiva and his symbol the lingam, Jayavarman as a Buddhist identified himself with the Buddha and the bodhisattva.

The Bayon has suffered numerous additions and alterations at the hands of subsequent monarchs. During the reign of Jayavarman VIII in the mid-13th century, the Khmer empire reverted to Hinduism and its state temple was altered. In later centuries, Theravada Buddhism became the dominant religion, leading to still further changes, before the temple was eventually abandoned to the jungle. Current features which were not part of the original plan include the terrace to the east of the temple, the libraries, the square corners of the inner gallery, and parts of the upper terrace.

In the first part of the 20th century, the École Française d'Extrême Orient took the lead in the conservation of the temple, restoring it in accordance with the technique of anastylosis.

The temple is orientated towards the east, and so its buildings are set back to the west inside enclosures elongated along the east-west axis. Because the temple sits at the exact centre of Angkor Thom, roads lead to it directly from the gates at each of the city's cardinal points. Unlike Angkor Wat, which impresses with the grand scale of its architecture and open spaces, the Bayon "gives the impression of being compressed within a frame which is too tight for it."

The dimensions of the upper terrace are only approximate, due to its irregular shape.

The outer wall of the outer gallery features a series of bas-reliefs depicting historical events and scenes from the everyday life of the Angkorian Khmer.

Though highly detailed and informative in themselves, the bas-reliefs are not accompanied by any sort of epigraphic text, and for that reason considerable uncertainty remains as to which historical events are portrayed and how, if at all, the different reliefs are related.

A scene from the eastern gallery shows a Khmer army on the march; in the southern part of the eastern gallery a marching Khmer army (including some Chinese soldiers), with musicians, horsemen, and officers mounted on elephants, followed by wagons of provisions.

A scene from the southern gallery depicts a naval battle; this section shows Cham warriors in a boat and dead Khmer fighters in the water.

A market scene in the southern gallery shows the weighing of goods; the fish belong to a naval battle taking place above.

The outer gallery encloses a courtyard in which there are two libraries (one on either side of the east entrance).

Originally the courtyard contained 16 chapels, but these were subsequently demolished by the Hindu restorationist Jayavarman VIII.

The inner gallery is raised above ground level and has doubled corners, with the original redented cross-shape later filled out to a square. Its bas-reliefs, later additions of Jayavarman VIII, are in stark contrast to those of the outer: rather than set-piece battles and processions, the smaller canvases offered by the inner gallery are decorated for the most part with scenes from Hindu mythology. One gallery just north of the eastern gopura, for example, shows two linked scenes which have been explained as the freeing of a goddess from inside a mountain, or as an act of iconoclasm by Cham invaders.

Another series of panels shows a king fighting a gigantic serpent with his bare hands, then having his hands examined by women, and finally lying ill in bed; these images have been connected with the legend of the Leper King, who contracted leprosy from the venom of a serpent with whom he had done battle. Less obscure are depictions of the construction of a Vishnuite temple (south of the western gopura) and the Churning of the Sea of Milk (north of the western gopura).

The inner gallery is nearly filled by the upper terrace, raised one level higher again. The lack of space between the inner gallery and the upper terrace has led scholars to conclude that the upper terrace did not figure in the original plan for the temple, but that it was added shortly thereafter following a change in design. In addition to the mass of the central tower, smaller towers are located along the inner gallery (at the corners and entrances), and on chapels on the upper terrace.

Efforts to read some significance into the numbers of towers and faces have run up against the circumstance that these numbers have not remained constant over time, as towers have been added through construction and lost to attrition.

At one point, the temple was host to 49 such towers; now only 37 remain. The principal religious image was a statue of the Buddha, 3.6 m tall, located in the sanctuary at the heart of the central tower. The statue depicted the Buddha seated in meditation, shielded from the elements by the flared hood of the serpent king Mucalinda. During the reign of Hindu restorationist monarch Jayavarman VIII, the figure was removed from the sanctuary and smashed to pieces.

Jayavarman VII King of the Khmer Empire (c.1181-1215)

Reign: Khmer Empire: 1181-1218

Full name: Jayavarthon

Birthplace: Angkor

Died: 1218

Place of death: Angkor

Predecessor: Yasovarman II Indravarman

Successor: Indravarman II

Consort: Indradevi

Consort: Jayarachadevi (Queen's Sister)

Father: Dharanindravarman IIJayavarman VII (1125 - 1215) was a king of the Khmer Empire (c.1181-1215and was the son of King Dharanindravarman II (r. 1150-1160) and Queen Sri Jayarajacudamani. He married Jayarajadevi and then, after her death, married her sister Indradevi. The two women are commonly thought to have been a great inspiration to him, particularly in his unusual devotion to Buddhism. Only one previous Khmer king had been a Buddhist.

Jayavarman's Early Years

Jayavarman probably spent his early years away from the Khmer capital. He may have spent time among the Cham of modern-day Vietnam. In 1178, they launched a surprise attack on the Khmer capital by sailing a fleet up the Mekong River, across Lake Tonle Sap, and then up the Siem Reap River, a tributary of the Tonle Sap. The invaders pillaged the Khmer capital of Yasodharapura and put the king to death, as well as taking the Apsara dancers. Also in 1178, Jayavarman came into historical prominence by leading a Khmer army that ousted the invaders.

Returning to the capital, he found it in disorder. Early in his reign, he probably repelled another Cham attack, quelled a rebellion, and rebuilt the capital of Angkor. Over the 30 some years of his reign, Jayavarman embarked on a grand program of construction that included both public works and monuments. As a Mahayana Buddhist, his declared aim was to alleviate the suffering of his people.

One inscription tells us, 'He suffered from the illnesses of his subjects more than from his own; the pain that affected men's bodies was for him a spiritual pain, and more piercing.'The declaration must be read in light of the undeniable fact that the numerous monuments erected by must have required the labor of thousands of workers, and that Jayavarman's reign was marked by the centralization of the state and the herding of people into ever greater population centers. Historians have identified three stages in Jayavarman's building program. He constructed his own 'temple-mountain' at Bayon and developed the city of Angkor Thom around it.

Ta Prohm

In 1186, Jayavarman dedicated Ta Prohm ('Ancestor Brahma') to his mother. An inscription indicates that this massive temple at one time had 80,000 people assigned to its upkeep, including 18 high priests and 615 female dancers. The first Lara Croft film was shot in Ta Prohm as well as a few scenes from the movie Troy.

Preah Khan

Jayavarman also built the temple and administrative complex of Preah Khan ('Sacred Sword'), dedicating it to his father in 1191.

Angkor Thom and Bayon

At the centre of the new city stands one of his most massive achievements -- the temple now called the Bayon, a multi-faceted, multi-towered temple that mixes Buddhist and Hindu iconography. The reliefs show camp followers on the move with animals and oxcarts, hunters, women cooking, female traders selling to Chinese merchants, and celebrations of common footsoldiers. The reliefs also depict a naval battle on the great lake, the Tonle Sap.

Fixing the Dates

The historical record is a mixture of the incredibly precise (we know the exact date that a temple was consecrated) and more ambiguous texts and archaeological evidence. Many of the dates marking the life and reign of Jayavarman VII are a matter of conjecture and inference. There is a minority view that the current biography of Jayavarman is imaginary and that the evidence could just as easily support the view that he was the usurper.

One date that has been generally accepted is 1177 when the Chams, who had themselves been subjected to numerous Khmer invasions, took the city of Yashodharapura. A Cham king took the title of Jaya-Indravarman.

In 1181 Jayavarman VII became King after leading the Khmer forces against the Chams. Jayavarman died in about 1215, at an advanced age ranging from 85 to 90. Indravarman was succeeded by Jayavarman VIII who it is thought supported a Hindu revolt. The niches all along the top of the wall around the city contained images of the Buddha. A statue of Jayavarman VII was found by excavators having been thrown down a well. Buddha images in Preah Khan were re-worked to resemble Brahmins. When Cambodia finally did become a Buddhist country, it followed Theravada Buddhism, not the Mahayana Buddhism practised by Jayavarman VII.

Interpretation

Care must be taken not read European patterns of kingship, inheritance or nationhood onto the history of the Khmer empire. Sons did not necessarily inherit their father's thrones; Jayavarman VII himself had many sons, such as Suryakumara and Virakumara, who were crown princes (the suffix kumara usually is translated as crown prince).

Jayavarman VII remains a potent symbol of national pride for present day Cambodians. This has contributed to a legend of the Buddharaja, the King-Buddha, who privileged compassion in ruling. This view of Jayavarman and his reign is supported by some beautiful portrait sculpture of him in meditation.

References

A fictionalised account of the life of Jayavarman VII forms the basis of Geoff Ryman's 2006 novel ‘The King's Last Song’.

Statue of Jayavarman VII, Guimet Museum http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:JayavarmanVII.jpg

Angkor's North Gate Siem Reap, Cambodia Map

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

If you love our website please add a like on facebook

Please donate so we can make this site even better !!